Osa Peninsula is the best place to see all four species of Costa Rica monkeys in the wild. By “seeing” I do not mean a theoretical possibility to get a fleeting glimpse of these fascinating creatures. I am talking about a real, almost guaranteed, opportunity to observe them in their natural habitat for hours and hours. Below are the details and photographs from our most recent trip to Costa Rica.

What Kind of Monkeys Live in Costa Rica?

There are four native monkey species to be found in Costa Rica:

- Central American squirrel monkey

- Mantled howler monkey

- Geoffroy’s spider monkey

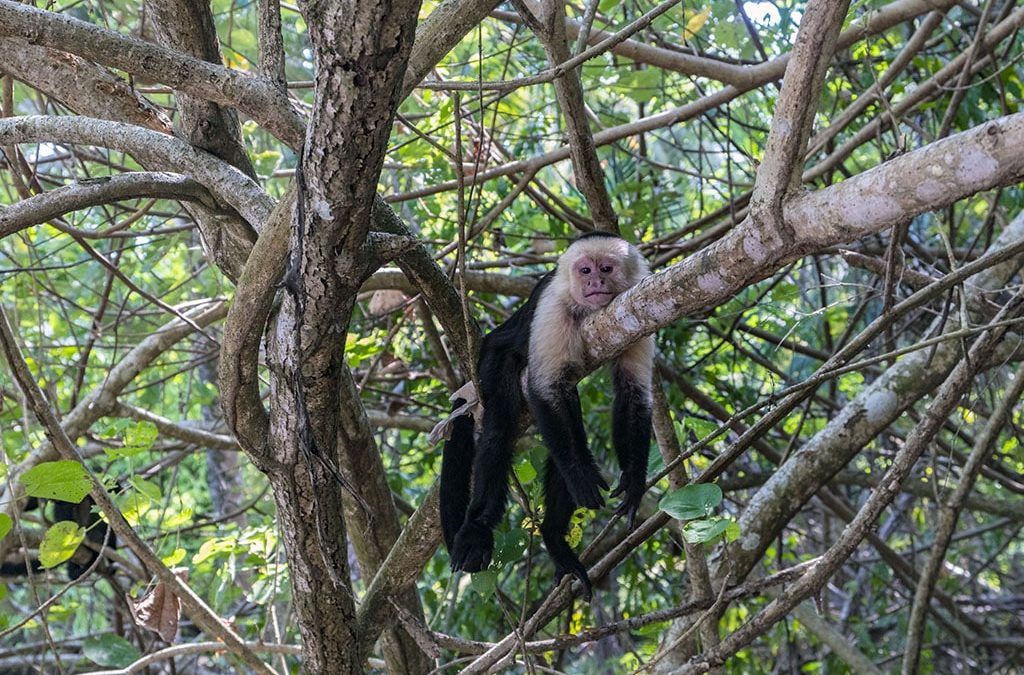

- White-faced capuchin

All of them have different, but partially overlapping habitats, dietary preferences and travel patterns. They also display a variety of interesting types of locomotion and behaviors when interacting with their “peers” and other animal species. Some monkeys are rather common throughout the country and the Central Ameraca, others are rare and near-endemic. Certain monkey species are especially shy and elusive, whereas, at least one group of Costa Rican primates, would “stalk” and even “harass” the humans when encountering them in the wild.

A Monkey Heaven of Osa Peninsula

Osa Peninsula, located in the remote south of Costa Rica, is the only single place in the country where all extant primate species still naturally co-exist. In fact, one of our nature guides from the local Lapa Rios ecolodge told us, that all four may be seen as they forage peacefully on the fruits of a single large tree.

While this tale might be a bit of an exaggeration, it is not too far from the reality. To enjoy multiple close and casual encounters with the monkeys, all you would need is sufficient time (5-7 days, is my estimate), patience and a good local travel base on the peninsula. Matapalo Beach became such a place for us on our most recent trip to Costa Rica.

Matapalo, the less-traveled Gateway to Corcovado

In fact, you even do not have to venture out inside the Corcovado National Park itself to see all 4 Costa Rican monkey species up close. Wildlife does not recognize the boarders created by humans. A recent study conducted around the Carate Gate of the national park by a group of Frontier’s volunteers demonstrated that quite convincingly. The staff at the local ecolodges, which use camera-trapping as a non-invasive assessment of the movement and abundance of larger animals, have also told us about the “wildlife spillover” they were witnessing in the recent years. According to them, many mammals, including those still considered endangered, were moving in and out of the Corcovado National Park in search on new mates and territories. On our most recent trip to Costa Rican jungle, we made a similar conclusion about the country’s primates: the chances to spot all species of wild monkeys are very good around Cabo Matapalo, just outside of the Corcovado National Park.

Costa Rican Monkeys Under Pressure

The fact that all four monkey species of Costa Rica can successfully co-exist on Osa Peninsula is not unusual for the New World Neotropics. Interestingly, scientists estimated the average number of Central and South American monkey species sharing territory as 6 +/-3.6 (Peres and Janson, 1999).

Across Americas, the monkey populations have been declining, threatened by habitat fragmentation and loss to agriculture and infrastructure development, increased tourism and illegal pet trade. Although, such trends have been largely reversed in Costa Rica, two monkey species remain significantly affected by the previous and more recent negative ecological changes. In case of dietary overlap and during periods of decreased availability of food sources and suitable habitat, the pressure of competition might increase. But these loss of resources does not affect all four Costa Rican monkey species equally. Whereas the Capuchins and the Howlers have been relatively successful surviving and thriving under the environmental pressure, the Spider and the Squirrel monkeys have remained particularly vulnerable.

Why Howler Monkeys Roar and Grunt?

These are the primates, which you will hear more often than see. Despite their terrifyingly loud grunts and roar at dawn and dusk, Costa Rican Golden Manteled Howler Monkey (Alouatta palliata) are actually non-aggressive primates. In fact, they tend to be dominated both by spider and capuchin monkeys when they sometimes meet in the forest. During encounters with humans, they largely ignore them. Sometimes, however, howlers might express their displeasure by urinating (or worse) down on people from the canopy. You better watch out!

Howler monkeys mostly eat leaves (folivores) and sometimes fruits. Because of their nutritionally poor diet, these monkeys are low-energy slow-moving primates, who spend most of their time sleeping and resting. Even their loud acoustic system is believed to enable them to avoid confrontation with other groups without having to move around and spend too much energy. Unlike other Costa Rican monkeys, howlers almost never leap between branches. However, they display some unique forms of quadrupedal (using all 4 limbs) locomotion. A controlled head-first vertical descent along tree branches and lianas is one of them (watch it here). The animal will face the ground and walk down with both hands and feet grasping the support and the prehensile tail helping to control the movements. Only in a few species of non-claw animals have developed this rather uncommon type of locomotion. It is an adaptation for more energy-effective foraging at various levels of the forest canopy

Spider Monkey of Costa Rica

The Geoffroy’s Spider Monkey (Ateles geoffroyi) is among the largest of the New World primates and is native to Costa Rica. Like all other monkeys of Costa Rica, they are active during the day (diurnal) and live in the trees (arboreal species). They prefer spending time within high upper canopy of primary forests. Being large ripe fruit specialists (frugivores), they also eat leaves and occasionally seeds, flowers and even insects. Substantial amount of their water needs is covered by eating fruits and young leaves. However, spider monkeys also drink water from tree holes, epiphytes in trees and water sources on the ground. Their diet does not rely on extractive foraging techniques and does not require any significant manual dexterity. However, some anecdotal evidence of spontaneous tool use by wild spider monkeys (e.g. “females used detached sticks to scratch themselves”) has been reported.

Spider monkeys have developed curious locomotion adaptations of their arms, hands and prehensile (able to grasp) tail. These make them able to arm-swing in addition to leap from tree to tree. This combinatorial type of arboreal locomotion (leaping and brachiation) and prehensile tail places them into the “semibrachiator” or “tail-assisted brachiator” categories by primatologists.

Spider monkeys adhere to “fission-fusion” social system, in which smaller or larger “feeding parties” form and dissolve, depending on fruit availability. In the rainforest ecosystem, spider monkeys are important seed dispersers and as such play an important role in tropical forest regeneration.

Geoffroy’s spider monkeys have been reported to sometimes interact (even engage in mutual grooming!) with the Capuchins. However, we did not have an opportunity to see them interact with other monkeys.

While walking along a trail in the primary forest, we encountered a group of four male spider monkeys. They were not pleased to see us at all, swaying their arms and violently shaking the tree branches. By the King Louis Waterfall, however, we could peacefully observe two females with their young at a relatively close distance over a longer period. Read about the waterfall hike and wildlife viewing therein this blog post “King Louis Waterfall-Hike, Rappel, Monkey Watch”.

Due to their slow reproduction, frugivorous diet, and large territory requirement, spider monkeys are particularly vulnerable to disturbances. Currently, they are listed as endangered, with a decreasing population (IUCN, 2014).

Costa Rica’s Smallest Primates

The Central American Squirrel Monkey (Saimiri oerstedii) is the smallest and the most isolated of the five existing species of squirrel monkeys. Living predominantly in the Pacific lowland rainforests of Costa Rica and Panama, they travel in larger troops and often announce their presence with cheerful whistling and chirping. Squirrel monkey’s main diet consists of fruits and insects, but it also includes small vertebrates (frogs, lizards, even birds and bats). Currently, their conservation status is “Vulnerable, with decreasing population” (IUCN).

Interesting facts about Squirrel Monkeys:

- Synchronized birth. In a group, all females give birth within a single week! This is to reduce infant losses to predators, which are many and include raptors, such as Grey hawks and Roadside hawks and even Chestnut-mandibled toucans. During our visit to Costa Rica in late January, we did not observe the young of Squirrel monkeys. Reportedly, February through April is the best time of the year to see them due to better food availability.

- Association between Squirrel monkeys and birds. Certain kite, tanager and woodcreeper species were reported to follow troops of foraging Squirrel monkeys and take advantage of their feeding behavior. These clever birds have learned to pick up the insects and invertebrates exposed by the monkeys during the feeding sessions.

The “Little Aggressor” and “Great Innovator”

White-headed Capuchin Monkey (also known as the White-faced or White-throated Capuchins (Cebus capucinus)) is one of the most common monkey species in Central America. Unlike other Costa Rican primates, which predominantly feed on tree leaves, fruits and insects, capuchins also hunt squirrels, coati pups and other mammals. They represent a group of so called “omnivorous extractive foragers”. Many species of mammals and birds from this ecological niche are known for their “cleaver approaches”, not only in feeding, but also in other aspects of their lives. Scientists believe that the relative abundance and survival success of Capuchins are attributed to their remarkable adaptability and great variability in behavior. See this short video of their social interactions.

A group of UCLA scientists, who studied “innovative behavior” in Costa Rican Cebus capucinus, reported, that “capuchins, relative to other ape species, devote a higher proportion of their creative energy to investigation of their environment and devising new social behaviors and a lower proportion to comfort-related behaviors and foraging”. “Capuchins devoted about 42% of their innovation repertoire to the investigative domain compared with chimpanzees (31%) and orangutans (14%)”! The older animals appeared to be more inventive within social behaviors, whereas younger monkeys were innovative in other contexts.

Interesting facts about Capuchin Monkeys:

- Encounters between groups of capuchins are mostly hostile in nature and bloody male takeovers, followed by infanticides, are common.

- A group of Capuchins would easily displace Howler monkeys, despite profound difference in size. However, a group of spider monkeys (who have larger dietary overlap with the capuchins in fruit consumption) seem often have the upper hand.

Capuchins are known for frequently interacting with and investigating other species (potential predators, prey, and feeding competitors). They often mob their predators, no matter how large (including Caymans, raptors and big cats!). Do not get surprised by being “stalked” by capuchins while in the woods! These monkeys do harass so-called “neutral species” (non-threatening and non-competing), including humans. Why are they doing that? Primatologists do not have many solid explanations, other than the underlying aggressive temperament, innate curiosity and investigative nature of Capuchins as a species.

To learn more on this subject, read “Interspecific Interactions between Cebus Capucinus and Other Species: Data from Three Costa Rican Sites”