by mytravelcurator | Jun 8, 2019 | Central America, Costa Rica

During our recent trip to Southern Costa Rica, we eagerly joined the “Twigs, pigs and garbage” (aka Sustainability Tour) at Lapa Ríos. Perched on a hill over the Matapalo Beach on Osa Peninsula, this ecolodge runs this special 2-hour walk to educate its guests and other local visitors about “true green” hospitality combined with environmental protection. It also reveals a fascinating story of an ordinary American couple on their quest to save a unique forest and to support local livelihoods.

Our Walk Guide

On a hot and sticky January afternoon, our small group of 4 travelers from New England met at a shaded gazebo. There we were greeted by Clare, the only non-native employee of the lodge at the time. A Florida University biologist in her gap year and aspiring environmental lawyer, Clare shared a few captivating stories about Lapa Rios, its humble beginnings and the ambitious mission.

Meeting our Tour Guide

Lapa Rios Founders – An American Couple on a Mission

The story of John and Karen Lewis, the Lapa Ríos founders was downright enthralling. In the early 90s, this American couple (a lawyer and a music teacher, both long-time Peace Corps volunteers) sold all their possessions and “raided” their retirement and profit-sharing funds. They soon settled down in a run-down hut on the newly purchased 1000 acres of primary forest on the remote Osa Peninsula in Costa Rica.

In an interview recorded for the 25-year anniversary of the Lapa Ríos ecolodge in 2018, Karen talked about the turbulent start, current challenges and future aspirations of this several-decade long project. She also spoke of the succession plan and how important it was to make sure Lapa Ríos stayed on its mission of protecting the last stronghold of the Pacific lowland rainforest in Central America. To read this interview in-full, check out the Earth Changers website.

A Success Story of Costa Rican “Green Tourism”

Costa Rica prides itself on being a green tourism destination. Nature tourism became a part of Costa Rica’s development policy in the 1970s and 30 years later it became the largest industry in the country. Since then, the “ecolodge-style” hospitality businesses quickly mushroomed throughout Costa Rica. However, their true nature as well as environmental and social impacts on local communities remain controversial. You can read some critical opinions in “Buying Up Nature: Economic and Social Impacts of Costa Rica’s Ecotourism Boom”, if interested. Still, even the skeptics seem to agree on Lapa Ríos Ecolodge’s remarkable success story.

CST Rating and National Geographic Society “Badge”

Back in 2003, Lapa Ríos was the first hospitality business in Costa Rica awarded the maximum 5 Leaf certification rating by CST (Certification for Sustainable Tourism) and it remained one of the few which pass this high bar during regular on-site audits.

The glamour of being the very first of the National Geographic unique Costa Rican ecolodges aside, Lapa Ríos must live up to its name. Delivering ecologically sustainable luxury in one of the most remote area of Costa Rica in no easy task. The Sustainability Tour which takes place on the ecolodge’s grounds offers a glimpse into behind-the-scene operations that make it possible.

The Man Behind the Main Lodge and the Mission Statement

After receiving the thorough introduction, we moved to the Lapa Ríos Main Lodge. Its architect, the late David Lee Andersen, was also a visionary of ecologically sustainable tourism and a long-time friend of Karen and John Lewis. He was also the man who coined the ecolodge’s original long-standing mission statement:

“No matter how you cut it, a rainforest left standing is worth more”

In addition to the eye-pleasing and airy design of the lodge, its “thatched roof” (which looks amazingly authentic) is NOT made of quickly decaying high-maintenance natural materials. It is produced from durable recycled plastic.

No Plastic Straws at Lapa Rios Bar

At the bar, well-stocked on liquors and non-alcoholic beverages, you won’t see any cans or plastic bottles. Plastic straws have also been replaced with elegant locally crafted bamboo stalks. All guests at Lapa Ríos are supplied with a reusable thermos filled with potable water and mounted into knitted poaches.

The Kitchen, Organic Garden and Compost

We move into the kitchen, were the gourmet meals are made to order daily, using locally sourced ingredients whenever possible and by-passing long-term storage. All of organic waste, including the food scraps from the meals, is manually sorted and either fed to the pigs or locally composted.

Pigs and Methane Gas

Happy Pigs of Lapa Rios Ecolodge

You are unlikely to meet the piglets and the “power house” they support while they eat your meal leftovers, unless you join the Sustainability Tour. We had to take a short drive to the service entrance of the ecolodge to see the pigpen, the compost area and other related housekeeping facilities.

The small vegetable garden had organically-grown pungent wild coriander along with other herbs and veggies. Next to the patch, there was a compost heap, which remained an ongoing project. The ecolodge continued to experiment with the best ways to degrade various types of organic materials, much of which is acidic.

Nearby, there was a small-scale roofed pig-parlor. Inside an airy enclosure, we found a dozen young hogs seemingly content, though making occasional grunts: “They must have just been fed”, Clare commented with a smile.

In addition to reducing food waste while “growing meat”, the capture and utilization of greenhouse gas methane the pigs generate has other ecological benefits. Through anaerobic digestion, this “low-cost system” of methane production creates renewable energy. Instead of burning firewood, propane or electricity, the low-cost biodigestors (see photo below) produce high-quality biogas, which is used for direct heating or for running a generator to create electricity for any other purpose.

Biogas Production from Pig Manure

Preserving Unique Wildlife of Osa Peninsula

During the tour, we learned that Lapa Ríos is not only committed to being a highly sustainable hospitality business. It is also a nature reserve with multiple ongoing projects, involved in direct wildlife protection. From its early days, the ecolodge has been expanding and improving natural habitat for the growing population of the unique Osa Peninsula fauna and flora.

The property is an integral part of the protected area and additional habitat for the wildlife “spillover” from the Corcovado National Park. Check out some of the images of these animals, including the endangered ones, such as puma, ocelot and paca, captured by the motion-activated cameras installed throughout the Lapa Ríos Nature Reserve.

Motion-activated Camera for Wildlife Surveys

The lodge’s impact on local environmental protection is reaching far beyond its borders. Reportedly, a salaried ranger position in the neighboring Corcovado National Park has also been supported by Lapa Ríos.

The Social Impact of Lapa Ríos Ecolodge

But protecting the nature and the livelihoods of local people at the same time is a tricky balance. For the founders of Lapa Ríos, the social aspect of the enterprise has been an important part of their “business model” and it continues giving back to the community in many ways.

Already 10 years ago, a group of scientists from Stanford University took a closer academic look at the “case of Lapa Ríos”. Through interviews, questionnaires and “before and after” forest cover comparisons they gauged the environmental and socioeconomic impact of the ecolodge on the local communities and rainforest conservation on Osa Peninsula. Their findings were made public in “Social and environmental effects of ecotourism in the Osa Peninsula of Costa Rica: the Lapa Ríos case”.

Giving Back to the Community

Many Costa Rican hospitality businesses make use of seasonal guest workers due to the natural swings typical for tourism industry. At Lapa Ríos you will meet over 70 full-time staff employees, most of whom are local to Osa Peninsula. Several nature tours we took through the lodge were guided by the local “veteran” Edwin, who has been working at the ecolodge for over 20 years.

In addition to direct support of nature conservation personnel within and beyond its borders, the ecolodge is also offering “Nature guide training” cources to anyone interested in becoming a part of Costa Rican green tourism.

Other programs at Lapa Ríos (such as “Dock-to-Dish” initiative) are committed to provide fresh locally-sourced food and other necessary sustainable materials for the ecolodge as well as stable well-paid jobs to the local fishermen, farmers and other small business owners.

Organic Long-leaf Coriander at Lapa Ríos

Investing into the Future

In the early days, all local kids in the area could only receive a few months-worth of schooling per year because the roads to the nearest school in Puerto Jiménez remained impassable most of the time. Nowadays, they are offered year-around education at the local Carbonera school established by the founders of Lapa Ríos. With continuing financial and social support, the former students are now working as teachers at the school and the virtuous cycle continues …

by mytravelcurator | May 19, 2019 | Central America, Costa Rica

The King Louis Waterfall, just off the Matapalo Beach Road is a hidden gem on Osa Peninsula in Costa Rica. One does not have to be exceptionally fit or daring to visit it, but some planning is required to make this trip a success. Read on to learn about the place, when to go and how to find it.

King Louis Waterfall Info

King Louis Waterfall in Matapalo

Time Required:

Depending on whether you are staying in Matapalo or coming from Puerto Jimenez, plan to spend 4 to 5.5 hours total (perfect as a half-a-day trip):

- 3 hours (with 30 min climb each way) for the waterfall visit itself

- 1 hour (30 min each way) to walk along Matapalo Beach Road

- 1.5 hour (40-45 min each way) to get to Matapalo Beach Road (if you start your trip from Puerto Jimenez)

- Best Time to Visit: starting early in the morning (around 7 am) is absolutely the best time to enjoy the solitude (before “the crowd” arrives), to have a better opportunity for wildlife watching, and to enjoy cooler temperatures

What to Bring:

- Water and food (there are NO shops or restaurants in the area)

- Hiking boots or comfortable non-slip sneakers (avoid flip-flops, sandals etc., we have seen tourists turning around half-way into the climb, because they did not have proper shoes to complete the hike all the way to the waterfall)

- Binoculars and/or camera with a long-lens for wildlife viewing

- Beach towels and swimwear for refreshing dips in waterfall pool, cascades and at nearby beaches.

How to get there:

- Drive or take a bus/taxi to the Matapalo Beach Road if you start in Puerto Jimenez

- Our advice: Do not drive on the Matapalo Beach Road! and take a pleasant 30-min walk (about 1 mile) instead

- At the very end of this dirt road by the beach, look for a short offshoot in the right and the “Catarata” sign (Spanish for “Waterfall”) on a tree trunk (see the blog picture above and follow the details further below). This is the head of the King Louis Waterfall trail

- Follow a poorly marked trail along the stream (we counted ONLY a handful of those “red-and-white” tags like the one attached next the “Catarata” sign) as you climb up all the way to the waterfall

Matapalo Beach Road to the Waterfall Trail

As I mentioned above, driving along the Matapalo Beach Road is not recommended, unless you have an ATV or a car with a VERY good clearance (simply having a standard 4×4 car is not enough). The road is riddled with deep potholes and littered with large rocks. Just be sure not to block any traffic (the local property owners, staff and some vacationers do take their pick-up trucks, dirt bikes and ATVs through there).

You can park your car by Playa Pan Dolce (the first beach off Matapalo Beach Rd.) as you leave the main road leading to the Carate Gate of the Corcovado National Park. If you do decide to drive on, but change your mind, you may also park your car by the Playa Carbonera down the road and walk the remaining distance. This is something we did after we realized the road was in a very poor condition.

If you set out in the morning, your walk will be mostly in the shade (until the very last few hundred feet). During this early hour, you might have your first wildlife-watching opportunities of the day. Spotting interesting birds is easy around here. On our walk along the Matapalo Beach road, we passed several small guided bird watching parties scouting the dense vegetation with their Swarovski scopes and binoculars.

Along the way, you will see occasional small lodges and private vacation homes.

Finding and Climbing the King Louis Waterfall Trail

King Louis Waterfall Trail Head Sign

Towards the end of the road, you will also be able to see the beach through the vegetation on your left. As the road starts curving sharply to the left, there is a smaller less-traveled “offshoot” on your right. Follow it for another hundred feet till you see a big tree with “Catarata” sign and an arrow attached to its trunk. If the road ended and you are facing the beach, you’ve walked a hundred feet too far.

Just as it is tricky to find the trail start, it is hard to know for sure where exactly the trail goes after you start your climb. If you begin early, you likely won’t see anyone there to show you the way. However, the rocky passage is rather narrow, and it is hard to get lost. One short section of the trail is equipped with a guide rope.

We did not meet a sole on the way up (while seeing at least 10 people on the way back). As you continue pushing forward, there will be a couple of smaller cascades on route to take a dip and cool down.

Swimming and Waterfall Rappelling

After a half-an-hour climb, we’ve finally reached the waterfall! It was the tallest waterfall we’ve seen in Southern Costa Rica so far. Surrounded by the massive mossy rocks and towering rainforest trees, we spent a couple of hours swimming, reading and enjoying the solitude.

If you are looking for even more adventure and a jolt of adrenaline, you may wish to look into other options to visit the King Louis Waterfall. Some local lodges in Matapalo and tour operators in Puerto Jimenez will offer you both tree-climbing and waterfall rappelling tours in the area.Check out this blog post for a vivid narrative about such a adventure.

Refreshing Dip into Waterfall Pool

Viewing Spider Monkeys by the Waterfall

Wildlife sightings is something one can hope for but can never be guaranteed. However, the remote location and proximity to the Corcovado National Park makes King Louis Waterfall area a perfect place for such rare encounters.

After we settled and quieted down by the “pool”, I suddenly spotted a couple of larger monkeys moving briskly through the canopy. A moment later, two more monkeys joined them in the same tree. Since we did bring our binoculars on this hike, I was happy to have my long camera lens as a substitute.

This was our first sighting of a Spider monkeys in Costa Rica (the second one was a rather brief encounter a few days later along the private Osa trail of the Lapa Rios Ecolodge). It was 2 female monkeys, each having a tiny white-faced baby clinging to their mothers.

There was also a younger adult, who was bouncing back and forth between “socializing” with the females (one of which was probably his mother) and carefully exploring the surroundings nearby on his own. The entire time, they seemed to ignore our presence and it was hard to take our eyes off this entertaining family scene.

The patch of the rainforest around the waterfall is a prime natural habitat for Spider monkey, who are frugivores and need to roam large areas with tall primary-growth trees and plenty of fruits to survive. Since this type of primary rainforest remains scarce, Spider monkey is currently one of the most endangered primate species in Costa Rica and Central America.

Spider Monkey Family by the Waterfall

We Will Be Back

All in all, this hike to the King Louis Waterfall was definitely one of the highlights on our trip to the Osa Peninsula. We would highly recommend it to nature lovers and adventure-seekers alike. While many Costa Rican waterfalls are slowly turning into crowded “tourist traps”, this one remains a pristine and quiet place. This also one of very few hiking opportunities in Matapalo with public access. Most hiking trails in this area are privately owned and their use would require special arrangements.

Enjoy Pristine Matapalo Beaches and More Wildlife

But wait, there is more. You might consider extending your Waterfall trip by visiting one or more of the nearby beaches on the way back. And not necessarily only for swimming and sun worshiping. You can follow the beach along the Matapalo Beach Road all the way back to the main road. Or you can combine walking in the shade with spending sometime on each of the gorgeous beaches.

On our way from the waterfall, while exploring the Carbonera Beach (halfway between the waterfall trail and the main road), we ran into a troupe of well over a dozen of White-faced Capuchin monkeys. We spent the next 45 minutes watching these highly social and dexterous foragers doing “their normal thing” in the bush.

White-faced Capuchins on Matapalo Beach

In truth, we were not sure, who was watching who during that thrilling encounter. It started a little “stand-off-ish”, as the alpha male approached us rather closely, while flashing his teeth. However, after a few tense minutes of “measuring up to his competition”, he plumped down on a nearby branch and assumed a rather relaxed napping posture (watch a 1 min video of this guy). Seemingly relieved, his entire following proceeded by going about their own business as well.

Despite all that grooming, eating and quarreling, they clearly kept an eye on us and what “we were up to” at every given moment. As I learned later from several reads on the subject, Capuchin Monkeys are often attracted by any “activities” on their territory. They are notorious for frequently “stalking” people and many other animal species. To learn more about the White-faced Capuchins and the other three species of monkeys we met during our week-long stay in Matapalo, read my post “Find all Costa Rican Monkey Species in One Place”

by mytravelcurator | Apr 27, 2019 | Central America, Costa Rica

One does not have to be a hard-core birder to enjoy bird-watching at Los Cusingos Neotropical Bird Sanctuary, just as

“One needs no scientific training to love a warbled song, or to warm to the sight of a parent bird bravely defending its helpless nestlings”

Skutch A.F. from Untitled, Journal, 1931

During a recent visit to Southern Costa Rica, we were looking into some unusual places for nature walks along Interamericana Highway (designated as Route 2 on the maps). We found Los Cusingos Bird Sanctuary to be such a place, with a long bird checklist (at the bottom of this post) and full of character.

Nesting Bronzy Hermit

The Bird Sanctuary covers 78 hectares, of which 50 ha. is primary forest and the remaining 28 ha. secondary growth. It has Dr. Skutch’s house-museum, a cabin and a small visitor center. The garden has a variety of marked native and exotic plants and trees. It also has a small nursery with flowering plants (including local orchids (some of them so tiny, that only high-quality macro photographs would make them full justice).

Why is Los Cusingos Worth a Visit?

The allure of the Los Cusingos is easy to understand once you know the story behind it. Even if you don’t, there are many reasons to spend a day or two at this place:

- Los Cusingos is the only sizable lowland premontane forest area with primary growth near San Isidro del General. The rest has been logged down without a trace.

- Over 300 bird species have been reported at Los Cusingos over the years

- Skillful and knowledgeable nature tour guide on site

- A bird feeding station is available for independent visitors on self-organized tours

- Los Cusingos is Alexander Skutch’s Home (now a museum and a resting place)

- Enjoy Pamela Lankester’s Garden with marked plants and trees and a small nursery on site

- See agouties, coatis, snakes and other wildlife in their natural habitat

- Well-preserved Indian petroglyphs dated back to Pre-Columbus time at the end of a trail

- Easy access from San Isidro del General (or, better yet, by staying locally in Quizarra)

- Easily walkable terrain and trails

Agouti frightened by a Coati

Birds of Los Cusingos

According to the census conducted the Tropical Science Center (which oversees the sanctuary), the avifauna of Los Cusingos counts over 307 species, half of which were resident birds. The bird sanctuary covers altitudes between 650 and 750 meters above sea level. Across the Talamanca Mountain Range, the variety of avian species changes with altitude. Thus, Los Cusingos makes a perfect location for watching birds, which prefer lowland and mid-elevation habitats.

Guided Bird-watching Tour in Los Cusingos

Our Local Guide at Los Cusingos

Our guide, a humble local guy J. Andres Chinchilla, was recommended to us by our Airbnb host in Quizarra. From the very beginning, he was responsive to our requests and generous with his time. You can contact cusingos@cct.or.cr to connect with Andres.

Being born and brought up locally, Andres worked for Alexander Skutch himself since he was 14. He actively participated in construction of the walk trails and other improvement projects at the Sanctuary. His dream is to supplement his tour-guiding job with building a few cabins locally and to expand his ecotourism-oriented business.

Slaty-tailed Trogon at Los Cusingos

Early Morning Bird-watching Tour

We met at the gate bright and early, before the Sanctuary “gates” even opened (another advantage of staying locally and going with a local guide). Equipped with a high-quality Swarovski scope and intimate knowledge of Los Cusingos native and migratory birds, Andres spent almost 6 hours birdwatching with us. “Patience is a virtue of a lucky birder”, he remarked to us, while setting up his scope in the garden and taking out a couple of bananas out of his backpack.

Female Honey Creeper at the feeder

If you do not have a tour guide, you can still use a bird feeding station by the garden to observe a variety of birds. Just remember to bring a few ripe bananas for this purpose. During our visit, Speckled Tanagers, Shining Honeycreepers and Green Honeycreepers, Spot-crowned Euphonias and Cherrie’s Tanagers were not shy at the feeder.

Along the edges of the garden, we also observed the famous Fairy-billed Aracari, Red-capped Woodpecker, several species of Hummingbirds and a Blue-capped Manakin gulping dark-blue fruits of melastomes in the air. That morning, we were also lucky to get a fleeting glimpse of the endangered Turquoise Cotinga.

Peñas Blancas River

After spending a couple of hours in the garden, we started walking by the Peñas Blancas river and along the River trail. At the entrance of the Naturalist trail, the forest got denser and more mysterious, dominated by tall mossy trees covered with epiphytes, climbing woody vines and walking palms on spiny “stilts”. On the go, Andres spotted several elusive resident birds and got them on the scope and “in the frame” for us. By the time we circled back to the garden, our bird list grew substantially longer and included Blue Dacnis, Riverside Wren, Baird’s Trogon and Orange-collared Manakin. If you have specific the bird species on your wish-list, let Andres know and he will make you bird checklist glow with new entries within a short time.

Alexander Skutch House-Museum

Having spent a few hours birding, we could now immerse ourselves into the history of Los Cusingos and the fascinating life story of its former owners Alexander Skutch and Pamela Lankester. The House (now a museum) was built by Alexander Skutch himself and has changed little since the time the homesteading naturalist settled down there.

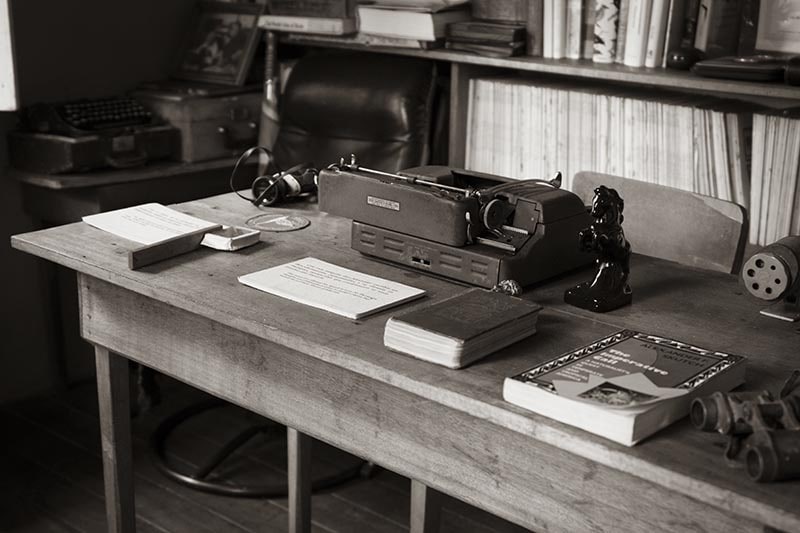

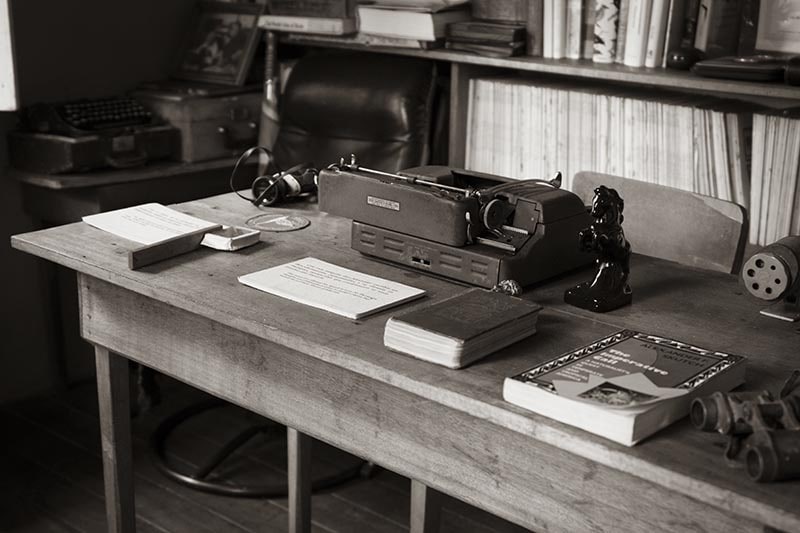

Alexander Skutch’s study

Browsing through the simply appointed rooms, one can easily sense the Skutch’s appreciation of a humble lifestyle and “work environment”. The original old typewriter, which was used for decades to capture his notes, articles and book manuscripts was still resting on his desk. The sturdy self-built wooden bookcase was fully loaded with “well-used” ornithology guide books and Skutch’s own volumes authored during his 60 years-long ornithology career. The man, who objected to banding or handling birds, let alone collecting them, came up with creative ideas for learning about them by mere observation. Some of his “inventions” are on display in his study along with his old binoculars and cameras.

Coffee with a View

After the walk and an insightful conversation with two other birding enthusiasts (the only other visitors we met at the Sanctuary that Sunday morning), we asked Andres about any local cafe nearby in Quizarra. He immediately hopped into his car and told us to follow him.

The local bakery, just a few hundred meters away, had two tables and a magnificent view. The variety of freshly made pastries in this little place was just too wide for us to navigate through. At the end, we settled for a couple of Andres’s favorites, a cup of famous Costa Rica-grown coffee and sat down to enjoy the vista over Valle del General.

View of Valle del General from the Bakery

Birdwatching North of Los Cusingos Bird Sanctuary

The northern section of the Alexander Skutch Biological Corridor is located at higher altitudes of Las Nubes Biological Reserve. It is bordering the Chirripó National Park and reports a large variety of avifauna, including several of the 28 described restricted-range regional endemics of the Talamanca Mountain Range. Long-tailed Silky-flycatcher (Ptilogonys caudatus), Black-faced Solitaire (Myadestes melanops) and Sulphur-winged Parakeet (Pyrrhura hoffmanni) are just a few examples.

A recently published book “Birds of the Alexander Skutch Corridor, Costa Rica” is a great resource, if you are interested in learning more about the avifauna of the entire Alexander Skutch Biological Corridor. This field guide covers 285 bird species recorded by the Faculty of Environmental Studies of York University (Toronto, Canada). The long list of birds includes 47 migratory species, 41 altitudinal migrants, 23 endemic species, and 11 near threatened or vulnerable species.

Los Cusingos Bird Sanctuary – Bird List

by mytravelcurator | Apr 19, 2019 | Central America, Costa Rica

Zamia is the only living genus of cycads native to Costa Rica. The most recent reports include 5-6 Zamia species (depending on the source), two of which are described by cycad experts as endemic (E).

- Zamia fairchildiana

- Zamia pseudomonticola

- Zamia acuminata (E)

- Zamia gomeziana (E)

- Zamia neurophyllidia

- Zamia obliqua

What are Zamia?

Zamia is a group of plants endemic to the New World (only live in the Americas). The first one identified was officially named Zamia pumila by Carl Linnaeus back in 1762. At that time, some West European botanical gardens (such as those in Leiden and Amsterdam) already had some specimens acquired during expeditions to the West Indies.

Costa Rican Zamia fairchildiana

How many Zamia in Central America?

79 Zamia species have been described and the list is constantly growing. Their present range spans most of the tropical Americas, from southeastern Georgia and Florida down to northern Argentina. In Costa Rica, Zamia grows on both the Pacific and Atlantic coasts.

Despite Costa Rica’s status as a biodiversity hotspot in Central America (and in the world), its cycad list is relatively short. In contrast, neighboring Panama (of a similar size to Costa Rica), has at least 17 different living Zamia species. Moreover, a huge variety of cycads has been described in Mexico (62 cycad species, including 17 Zamia). Nicaragua, on the other hand, has a single Zamia species (Zamia neurophyllidia), which is also “shared” with Panama and Costa Rica!

Zamia Biodiversity Hotspot or Not?

Puzzled by these differences, I have investigated and found a recent biogeographic Zamia study by an international group of scientists. This team analyzed the genetic “relatedness” of 70 American Zamia species using leaf DNA samples from Cyclades plants of known origin (found in the wild or from botanical collections). By doing so, they were able to organize them in 3-4 related clusters.

According to the Zamia distribution map in a recent publication, there is a large “dead zone”, with no known living Zamia species. The gap covers most of Nicaragua, El Salvador and Honduras and separates the Mesoamerican group (which includes Mexico) from the Central American group (includes Costa Rica as its northern “frontier”).

Despite the numeric differences between Costa Rica and Panama in Zamia species, it is still reasonable to consider both countries as “biodiversity hotspots” for Zamia in terms of species density. See the diagram of Zamia species richness across South and North Americas.

Where to Find Zamia in Costa Rica

If you’d like to find Zamia fairchildiana and the closely related Z. pseudomonticola and Z. acuminata in the wild, the humid lowland and mid-elevation areas (up to 1600 m) along the Pacific Coast of the country would be the best spots. Most of the collected “plain-leaflet” Zamia samples and reports originate from the Puntarenas Province (Osa peninsula, San Vito area, La Amistad NP) and some areas of the bordering San José and Alajuela provinces.

The “pleated-leaflet” Zamia neurophyllidia (referred to as Z. Skinneri by older reports) with distinctive broad veined leaflets, has only been found on the Atlantic Coast of the country.

Zamia Collections of Wilson Botanical Garden and Finca Cántaros

Wilson Botanical Garden Cycad Collection

The easiest way to see Costa Rican Zamia cycads (the most common varieties) is to visit the Wilson Botanical Garden in San Vito. Although more known for its world second largest collection of palm trees, it also has a variety of Asian, African, Australian and American cycads. Many of the cycads in the botanical garden are large mature plants and several had either female or male cones “on display” during our January visit.

On our recent trip to Southern Costa Rica, we have also found plants of Zamia fairchildiana in the “Zamia Zone” of the gorgeous private gardens of Finca Cántaros (open to the public). This small “nature reserve” is located just a couple of miles away from the Las Cruces Biological Station and the Wilson Botanical Garden and is well worth a 1-2 hour visit.

Costa Rican “Cycad List” in Flux

The original Costa Rican cycad taxonomy was compiled by Luis Gomez in 1982, a prominent Costa Rican botanist and former director of Museo National of Costa Rica and Las Cruses Biological Station and Wilson Botanical Garden. It listed 6 species, including the only known epiphytic (growing on trees) form of Zamia, Z. pseudoparasitica. That species was never confirmed living in Costa Rica and is considered a Panama endemic. Z. chigua has been removed from that list. Moreover, the Costa Rican Z. skinneri has been reclassified into the closely related Zamia neurophyllidia.

Recently Discovered Costa Rican Zamia

The relatively new species of Zamia gomeziana (similar in appearance to the Zamia species of the Pacific slope) was found on the Atlantic coast in Limón Province in 2010. The new species has been so far represented by a single female plant, but the hopes are still high to find more samples in the same remote region bordering Panama.

Reading the story of this new Costa Rican Zamia, brought back the memories of the “loneliest cycad in the world” (we stumbled upon in the Kirstenbosch Botanical Garden, while visiting Cape Town in South Africa). Only a single male plant of this species (Encephalartos woodii) was ever found in the wild. However, one hundred years later, close to two hundred individual plants grown from the original cycad can be found today in various botanical gardens and even in some private collections around the world. Despite its much more modest looks in comparison to E. woodii, there is still a hope that Zamia gomeziana will not disappear without a trace.

Z. gomeziana’s name was dedicated to the prominent Costa Rican botanist Luis Diego Gómez after his passing in 2009. In addition to the original classification of the Costa Rican cycads, Dr. Gomez made a remarkable contribution to “mapping out” and describing countless plant species of the country. He also served as a director of the National History Museum in San Jose and the renowned Las Cruses Biological Station in San Vito. Under his tenure, both institutions (including the Herbario Nacional) flourished and attracted wide attention and support from the international scientific community.

“Pick Your Poison”

Hairstreak butterfly larvae gorging on zamia

During our visit of the Cycad section of the Wilson Botanical Garden, we could not help but notice the bright-colored caterpillars gorging on zamia leaflets. Like most other cycads, Costa Rican zamia are poisonous to animals and humans. However, it is not toxic to these larvae of of White-tipped Cycadian (Eumaeus godarti), a small colorful Hairstreak butterfly, which prays on leaves and cones of Costa Rican zamia.

Despite the damage to the plants, some experts believe that this butterfly and Zamia might be in a mutually beneficial relationship called “opportunistic semi-mutualist symbiont”. I know, it is a mouthful for the most of us. By eating the “casing” of mature female cones of zamia, but leaving the seeds intact, the larvae might help cycads to disperse their seeds and to speed up the germination process.

As for the poison, the insects store and use the ingested toxic substance produced by Zamia against their own enemies, who will think twice before grabbing their dinner. Those bright colors of the larvae are just the “keep-off’ signal to their potential predators.

by mytravelcurator | Apr 13, 2019 | Central America, Costa Rica

Our search for “extraordinary” bird-watching places during a trip to Southern Costa Rica was handsomely rewarded. Following a birding “expedition” to Los Cusingos Bird Sanctuary, here it is what we’ve learned about it and the surrounding Alexander Skutch Biological Corridor.

What is a Biological Corridor?

First, a few words about the concept of Biological Corridors. It represents one of the most important conservation strategies currently promoted by the National System of Conservation Areas (SINAC) in Costa Rica. The purpose of a biological corridor is to provide connectivity “between protected wild areas, as well as between landscapes, ecosystems and habitats, natural or modified being rural or urban to ensure the maintenance of biodiversity and ecological processes and evolutionary; providing spaces of social agreement to promote investment in the conservation and sustainable use of biodiversity in those spaces.”

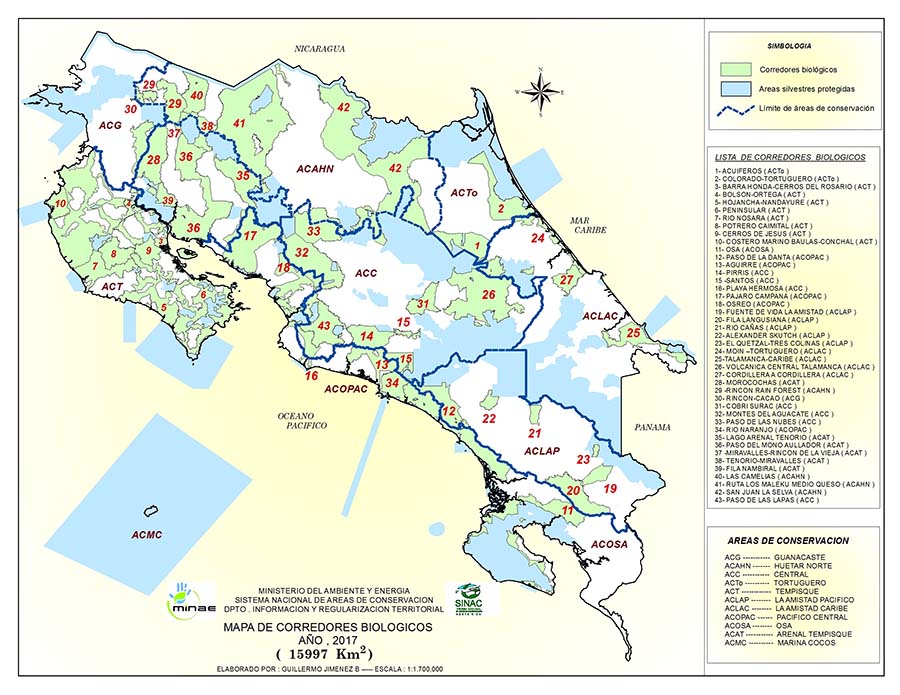

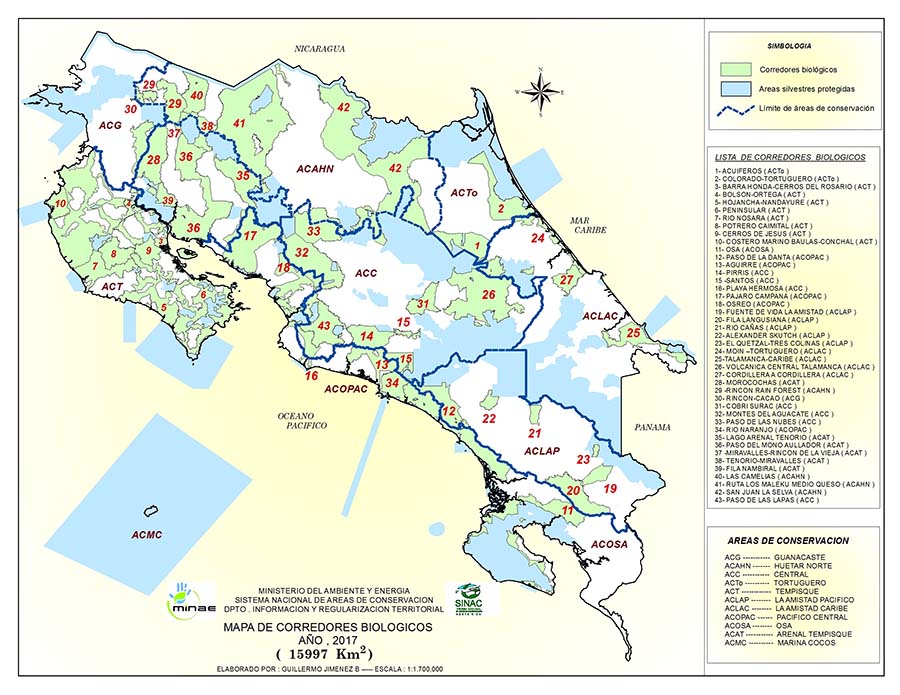

Costa Rica has a total of 47 biological corridors, which collectively cover over 30% of the country’s territory. The Alexander Skutch Biological Corridor (ASBC) is represented as #22 on the map of all Costa Rica’s biological corridors (SINAC).

Biological Corridors of Costa Rica (SINAC)

Bird-Haven of Alexander Skutch Biological Corridor

Alexander Skutch Biological Corridor is situated in the El General Valley, between the Talamanca Mountain Range and the Coastal Mountain Range (Fila Costena). ACBS was created in 2004 to protect the area within the Rio Peñas Blancas watershed. This type of habitat is called Tropical Premontane Wet Life Zone. The area is a home for a variety of residential bird species and a “safe haven” for altitudinal and long-range migrants. According to the census conducted by the Tropical Scientific Center (which now operates Los Cusingos Bird Sanctuary), over 300 avian species have been recorded over the years, 200 of which has been described by Alexander Skutch himself.

Stretching between the lowlands of Los Cusingos Bird Sanctuary (elevation 650-750 m) in the south and the mid-elevation premontane forest (1200-1500 m) of the Las Nubes Nature Reserve in the north, Alexander Skutch Biological Corridor offers birdwatchers an opportunity to observe residential and migratory birds within different altitudes bands.

The corridor’s northern boundary is also a gateway to the highlands of Mount Chirripó. This area within the Chirripó National Park has its own unique habitat and population of birds, including endemic species, such as Volcano Hummingbird (Selasphorus flammula).

Birdwatching in Los Cusingos

Plants of Los Cusingos

“The forest is the cathedral in which I worship”

A.F. Skutch. “A question”, May 17, 1942

Los Cusingos is one of the last remaining forested lowland areas in El General Valley. In addition to animals, the refuge is home to a wide variety of plants. 298 native species of trees, shrubs and vines have been reported by a recent survey of the refuge (referenced below).

The most diverse group is Melastomataceae family (35 different species were reported), which is rather typical for mid-elevation areas of Costa Rica. The dark-blue fruits of melastomes serve as a popular food source for birds in the sanctuary, especially among manakins and tanagers. Birds ‘return the favor” by doing a great job as seed dispersers for this ubiquitous group of plants (Stiles & Rosselli, 1993).

Several fern species, including endemic and threatened species, such as Cyathea bicrenate and Cyathea multiflora, can be spotted near the garden and along the trails. A dozen palm species have also been described in Los Cusingos, including a walking palm (Socratea exorrhiza or chonta) with distinctive widely spaced roots covered with spines.

Walking Palms

Rare plants, such as vulnerable Tocoyena pittieri and endangered Weberocereus imitans, Costa Rican endemics Tabernaemontana pauli and a native bamboo species Chusquea simpliciflora have also been recorded.

“A survey of the woody and climbing plants of the Refugio de Aves Dr. Alexander Skutch, “Los Cusingos”, Perez Zeledon Canton, Costa Rica” contains a full list of 314 species of trees, shrubs and vines of Los Cusingos (217 genera and 84 families).

Brief History of Los Cusingos, Alexander Skutch’s Home

Around the time Alexander Skutch Biological Corridor was created, a questionnaire survey of visitors to Los Cusingos was conducted. Surprisingly, most travelers to the area were not familiar with Dr. Alexander Skutch’s life and contribution to the field of neotropical ornithology.

I sure hope it’s been changing. The man had a fascinating scientific career (including his dramatic professional makeover) and an inspirational life philosophy. It does not take a trivial amount of courage to quit a successful post-doctorate job as a botanist (during the Great Depression!) to make a transition into a brand-new field of ornithology. This remarkable “foliage to plumage” makeover eventually resulted in publication of 20 scientific books and over 200 articles about tropical birds (in addition to dozens philosophy books and papers).

Gary Stiles (who together with Dr. Skutch co-authored one of the most popular books on tropical birds “Guide to the Birds of Costa Rica”) rightfully stated:

“The legacy of Alexander Skutch to Neotropical ornithology is, quite simply, the largest body of natural-history information ever collected by a single observer.”

Here is an extensive bibliography of Alexander Skutch. This collection of books and articles (many of which are in a pdf format) is a great resource for any birding enthusiast or anyone interested in Alexander Skutch’s legacy in science and philosophy. You can also learn more about Alexander Skutch’s career transition and his first years living in Los Cusingos from his notes, which were edited and compiled by Peter Scheers: “Early Views of Alexander F. Skutch: Selection from his nature diaries, philosophical notebooks (1929-1941)”.

Writing Desk and Typewriter of Alexander Skutch

Interestingly, a genus of birds bore Dr. Skutch’s name (Skutchia), in recognition of his contribution to the field of ornithology. Unfortunately, the monotypic Skutchia genus (with a single ant-eater species Pale-faced Antbird (Skutchia borbae)) was recently merged into Phlegopsis (Thamnophilidae), based on genetic evidence.

During his post-doctoral studies in Panama, Skutch became increasingly interested in neotropical birds. This powerful calling turned later into a lifelong passion and second scientific career. Spending all his time “in the field”, Alexander Skutch has described and published feeding, nesting, parenting behaviors and sociobiology of over two hundreds of neotropical bird species.

However, before Skutch made a name for himself in ornithology, the botanical projects were “paying his bills”. For almost a decade, Skutch was embarking on various expeditions to collect plants for botanical gardens, universities and natural history museums around the world. National Herbarium in Washington, the Arnold Arboretum of Harvard University, Kew Gardens, the Naturhistoriska Riksmuseet, the Missouri Botanical Gardens, Field Museum in Chicago, the New York Botanical Gardens, were all among Dr. Skutch’s customers buying his herbarium specimens.

After a decade of saving money and searching for a perfect place to call his own, Skutch’s dream finally came true. In 1941, he paid 5000 colons for 53 hectares of farmland and primary growth forest on the banks of Peñas Blanca River in the El General Valley. A year later, Skutch expanded the property to 77 hectares by buying a neighboring farm. This became “Los Cusingos”, Alexander Skutch’s home for over 60 years.

El Río Peñas Blancas

“Los Cusingos” – What is in the Name?

Los Cusingos is the local name for the Fiery-billed Araçari (Pteroglossus frantzii), a smaller member of the toucan family, which is fairly common in the area. Although these birds (characterized by Dr. Skutch himself as “presumptuous bandits” for their distinctive behavior) were not among his “favorites”, Skutch named his farm by their vernacular name (los cusingos) to keep it simple and easy for the locals to pronounce. The birds of his choice, the Jacamar, did not have a common Costa Rican name at that time.

Early Days of Los Cusingos

With the purchase of “Los Cusingos”, Skutch became a homesteading naturalist, who truly appreciated a simple, almost ascetic, lifestyle. It allowed him to “use a small stock of energy for contemplation of the eternal truths”. Despite his academic background, Skutch did not shun manual labor. He built his own house and made wooden furniture (most of which visitors can still see in the House Museum at Los Cusingos).

“I love the unspoiled aspects of nature, forests and rivers and mountains, and shall never long be happy separated from them. I would rather earn my daily bread by the humblest rural occupation than occupy the most envied professorship at a university in some great city”

A.F. Skutch. Untitled, Journal, 1931

As a life-long vegetarian, he also grew his own food, including rice and beans, coffee and sugar cane. He, and later his family, remained living “off-the-grid” for almost 50 years, until mid-90s (when his wife, Pamela, at last, convinced him to get connected to electrical power and to buy their first refrigerator).

House of Alexander Skutch

In the early years, Skutch faced a great deal of adversity at Los Cusingos. He struggled through forest fires, sickness of his farm animals, and troubles with the neighbors, who did not “keep their pigs at home” or pay back their debts.

Early in the newfound career, Skutch also struggled to get his first tropical field ornithology books published anywhere. In 1944, he wrote:

”But in dedicating myself to the study of nature, I also committed myself to making my discoveries available to others. In this last I have lamentably failed; my books without exception remain unpublished”

“Study of the birds,” Thoughts, Vol. 2, June 8, 1944

Then came the recognition. In 1946-1947, he received a fellowship from Guggenheim Foundation, a renowned American scientific institution. Soon after, in recognition of his publications on Central American birds, he also became a Fellow of the American Ornithologists’ Union (AOU).

Despite enjoying the solitude of the tropical forest, Skutch did not seem to be fully content with his reclusive life of a bachelor. In 1950, he married Pamela Lankester (Lancaster), a daughter of an English naturalist and orchid enthusiast Charles Lankester (whose private gardens became one of the best botanical gardens and plant research centers of Costa Rica and is now named in his honor Jardin Botanico Lankester).

According to Skutch himself, Pamela’s arrival to Los Cusingos improved their “public relations with the neighbors”. Later, the couple adopted Edwin, a son of a local worker. Pamela and Alexander Skutch had lived happily at “Los Cosingos” until their last days, and were both buried on the grounds of the Bird Sanctuary, behind their house. Dr. Skutch passed away on May 12 (2004), just 8 days before his 100-years birthday. Pamela died 4 years prior.

Alexander Skutch Festival

Despite his uneasy early relations with the neighbors in Quizarra, Alexander Skutch’s legacy (and later his wife Pamela) had a profound effect on local community development. To celebrate his life and contribution, Alexander Skutch Festival was organized in 2013 by the York University Professor Felipe Montoya, as a part of the Las Nubes Project.

Ever since, the festival became a popular community tradition with mountain bike races around the Alexander Skutch Biological Corridor, horse races, soccer games, and much more. The festival is held every May on a weekend closest to Alexander Skutch’s birthday (May 20th). The proceeds from the sale of food and beverages during the festival go to the local school funding. For more information about the festival, check out the Las Nubes Project’s website.

by mytravelcurator | Apr 6, 2019 | Central America, Costa Rica

Los Cusingos Bird Sanctuary, the enduring legacy of the prominent American “botanist-turned-ornithologist” Dr. Alexander Skutch, is located in a small town of Quizarra. Although less visited than other birding hotspots in Costa Rica, it is one of the primary destinations for naturalists visiting El General Valley. On our bird-watching tour to Los Cusingos, we have met some “hard core” birders, who kept coming to this historic former “farm” year after year. Its solitude and the richness of the local avifauna where the major draws. Sightings of over 300 bird species (more than half of which are residential), have been reported for Los Cusingos by the Tropical Science Center (TSC), which currently oversees the sanctuary.

Staying next-door to Los Cusingos

One can reach Los Cusingos from San Jose (takes about 4 hours each way) on a day trip, but this is hardly a good option for an early-morning birding walk. A better alternative is to stay overnight in San Isidro del General, which has a wider selection of lodging options for any budget. The distance between San Isidro del General and Los Cusingos is about 9 miles (via Rt.326), with travel time of 20-30 minutes. The road is paved, except a couple of miles on gravel surface just before the sanctuary entrance.

“San Isidro del General is a most unattractive place – despite its attractive setting”.

This is a direct quote from Alexander Skutch’s notes, which describes his first impression of San Isidro del General upon his arrival in 1935. One may or may not agree with this assessment, but this unflattering mention of the place prompted us look for lodging alternatives closer to Los Cusingos. Quite naturally, we turned to Quizarra, a small village where the sanctuary was located.

What does the Word “Quizarra” Mean?

In case you’ve been wondering about the name: Quizarra is a common Costa Rican name for Ocotea, a tree which belongs to a larger family of plants, including the wild relatives of avocado. The fruits produced by these trees are an important food source for many local animals and birds, including the iconic Resplendent Quetzal. Unfortunately, Ocotea trees have also been traditionally used in Costa Rica as a source of commercial timbers.

Fruits of Quizarra (Ocotea) tree

Accommodations in Quizarra

Until recently, there have been limited lodging options in Quizarra itself (which has a population of just over 300 people). However, the recent expansion of the home-sharing businesses (such as AirBnB) into the countryside of Costa Rica, made “staying nearby” much easier. There are several “fincas, cabinas and casitas” for rent along Rt. 326 in Quizarra. In comparison to other parts of Costa Rica, the prices remain relatively low, varying between $20 and $75 per night.

You can rent a private room or an entire home or cabin. Some of the hosts speak English. Others – not so much. However, most will be eager to communicate with you by any available means. You can also think of it as a unique opportunity to brush up your high school Spanish or even to learn some basic expressions. I have even seen some hosts advertise their homes specifically for “Spanish language learners”. In these parts, it is common for several generations to live under the same roof or close nearby. While older folks might not speak English, their children, oftentimes, are fluent in one or two foreign languages (which are part of the curriculum in Costa Rican schools). It is also not uncommon for young Costa Ricans to go abroad for work and study. Many of them return home and start their own, often tourism-related businesses.

Our Home away from Home

Our cottage

During our recent trip to Southern Costa Rica, we stayed in Quizarra, hosted by a local Canadian expat and his Costa Rican neighbors Rocio and Pancho (who also have a cabin for rent next door). The house was fairly simple but had everything we needed for a good level of comfort. There was also a network of trails (with hikes) around the “farm” and a few of bird-feeding stations for observations around the house. One of the afternoons, we walked through the forested area, the remaining pasture land, all the way to the Pena Blanca River (where one can take a refreshing dip on a warm winter day).

Quizarra Dining

If you have self-catering in mind, you can stock on groceries in San Isidro del General or along Route 2. For dining out, there is a plenty of small and inexpensive eateries and cafes in the city. In Quizarra itself, your options will still be limited when it comes to dining. However, there is a couple of bakeries within walking distance from Los Cusingos. They are selling a wide variety of tasty pastries, freshly baked bread and coffee. We opted for spending more of our vacation time outdoors, rather than chasing dining places in the city or cooking our own meals. If this is your preference too, seek out lodging opportunities which offer home-cooked meals for their guests. Dona Rocio, our host’s neighbor, was preparing delicious traditional Costa Rican meals for us during our stay in Quizarra (breakfast $7, lunch and dinner ($10)).

Mural art on a bakery wall in Quizarra

Weather in El General Valley

During the dry season (December-April), the temperatures around San Isidro del General are very pleasant and there is little precipitation overall. Precipitation is the major seasonal weather variable in the region. It is on its lowest in February, with an average of 20 mm. September and October, are the rainiest months with precipitation of 400-500 mm on average. Nights are generally cool, whereas days are warm (but nor oppressively hot, as along the Atlantic and Pacific Coasts). On average, temperatures fluctuate between 62°F at night and 83°F during the day (16-29°C). This pattern remains largely stable throughout the year.

In the Heart of Alexander Skutch Biological Corridor

In the second half of the 20th century, most of the “low elevation premontane forest” around Quizarra have been cleared for agriculture and cattle ranching. This had dramatic impact on the local flora and fauna. There are environmental projects aiming to “repair” the continuity of wildlife habitat, fragmented by pastures and agricultural land. Los Cusingos Refuge is an important part of the Alexander Skutch Biological Corridor, which is one of 44 existing biological corridors in Costa Rica. By re-connecting the isolated patches of land, one would make more territory and resources available for native plants and animals. There are ongoing efforts to integrate ecotourism to ease agricultural activities. The idea is simple, but also ambitious. Attracting nature-lovers to Quizarra would economically support the livelihoods of the local people. It will make them less dependent on environmentally destructive farming practices and, thereby, promote nature conservation.

Pastures of Valle del General

Other Things to Do in and around Quizarra

There is plenty of things to do in the San Isidro del General region.

- Given the richness of the local avifauna, you can easily spend two mornings bird-watching in Los Cusingos (one with a local guide and one independently).

- We also spent a full day hiking the trails of the nearby Cloud Bridge Reserve. Located in San Gerardo de Rivas, it is just within one-hour drive from Quizarra. This private reserve also organizes birding trips and nature walks for its guests

- Finally, you can use Quizarra as a base to visit the Parque National Chirripo. Its entrance is located along the road to the Cloud Bridge Reserve. If you are looking for a challenge, a hike to Cerro Chirripo, the highest mountain peak in Costa Rica (12,530 ft/3820m) might be something to consider. This trip would require two days of your time, with an overnight stay in the park’s only camp. The remote area of Parque National Chirripo is famed for its vistas over the Atlantic and Pacific Oceans and as the coldest place in Costa Rica, with sub-zero temperatures down to 15°F (-9°C) recorded in the past.