by mytravelcurator | Oct 28, 2019 | Africa, Madagascar

Renting a car without a driver while traveling in Madagascar is possible and perfectly legal, but rather uncommon. And there are many good reasons for such a consensus among travelers. Before hitting the road, you can read about our experiences with Malagasy roads and driving conditions. Below, we share our thoughts about booking a rental car in Madagascar and what to expect from spending many days in a company of complete stranger(s) (your personal driver–guide, that is).

First, let me point it out – we love self-driving while on vacations. No other way of travel offers more flexibility and independence while travelling. There are places in the world, however, where driving around is just neither practical nor enjoyable. In our view, Madagascar is such a country.

Although a few intrepid souls still try their luck and do self-drive in Madagascar, the absolute majority of independent travelers visiting the country hire a car with a driver.

To Drive or Not to Drive

Our recent trip to the Southern Africa covered three countries, including Namibia, South Africa and Madagascar (see our complete trip itinerary here). While we were doing extensive self-driving in the former two countries, hiring a car without a driver in Madagascar just did not seem simple. Although we did find some occasional reports of “successful” self-drive trips on different travel forums, they did not cover our tentative route and described obstacles, which we were reluctant to go through on our trip to Madagascar.

Ferry Crossing over Tsiribihina River on the Way to Tsingy

Heading for Madagascar, one of the poorest countries in Africa, one has a plenty to worry about: personal safety, poor infrastructure and treacherous road conditions, overcrowded cities and villages, “ancient” car fleets and long distances between points of interest, just to name a few. In addition, our trip happened to coincide with the worst plague outbreak in Madagascar in the last 50 years. Although we cherished our privacy and independence, and had no prior experience with hiring a car WITH a driver, the compelling stories of fellow-travelers persuaded us to “go with the flow”.

Have your Itinerary Ready

Having done some research on the net, we had our tentative travel route penciled. The “grand plan” was to head out from Antananarivo (the capital) to Morondava on the west coast to spend a week visiting the unique deciduous forest of Kirindy and Tsingy Bemaraha National Park. Next we wanted to drive back to the central highlands and explore a couple of national parks and wildlife reserves along RN7 (without going all the way to Isalo). As a wrap-up, we would stay 5 days hiking in the primary and secondary rain forests of the Andasibe area east of Tana (Antananarivo).

Driving Across a Bridge in Andasibe

Choosing a Car Rental Agent

With this itinerary in hand, we contacted 7 travel agencies, which were offering car rentals in Tana, and asked them for quotes and advice regarding our route. Most tour operators (except those who were primarily selling tour packages) got back to us with reasonably consistent rates for car rental $65-75 per day for a four-wheel drive (4×4) car (SUV). These rates also covered the cost for an English-speaking driver (including his accommodation and meals). The fuel was extra (also some rental companies did bake it into their quotes).

Some tour operators tried to talk us out of visiting Tsingy Bemaraha on the West coast due to the impassable roads in the area during the wet season. We were traveling to Madagascar in November just before the rainy season, but we decided to keep our itinerary unchanged and to try our luck. To learn about the advantages and the drawbacks of traveling to Madagascar, Namibia and South Africa during the shoulder (off-peak) season read this post.

After a brief period of email exchanges, we zeroed down on GMT+3 (Great Madagascar Tours) agency, which was run by a local couple out of Antananarivo. Anja was very responsive to all our inquiries and requests and it made all the difference for us. We felt we could trust this business with our upcoming adventure and the 20% credit card deposit (which, by the way, was the simplest and the most reasonable arrangement relative to what the other car rental agencies were proposing).

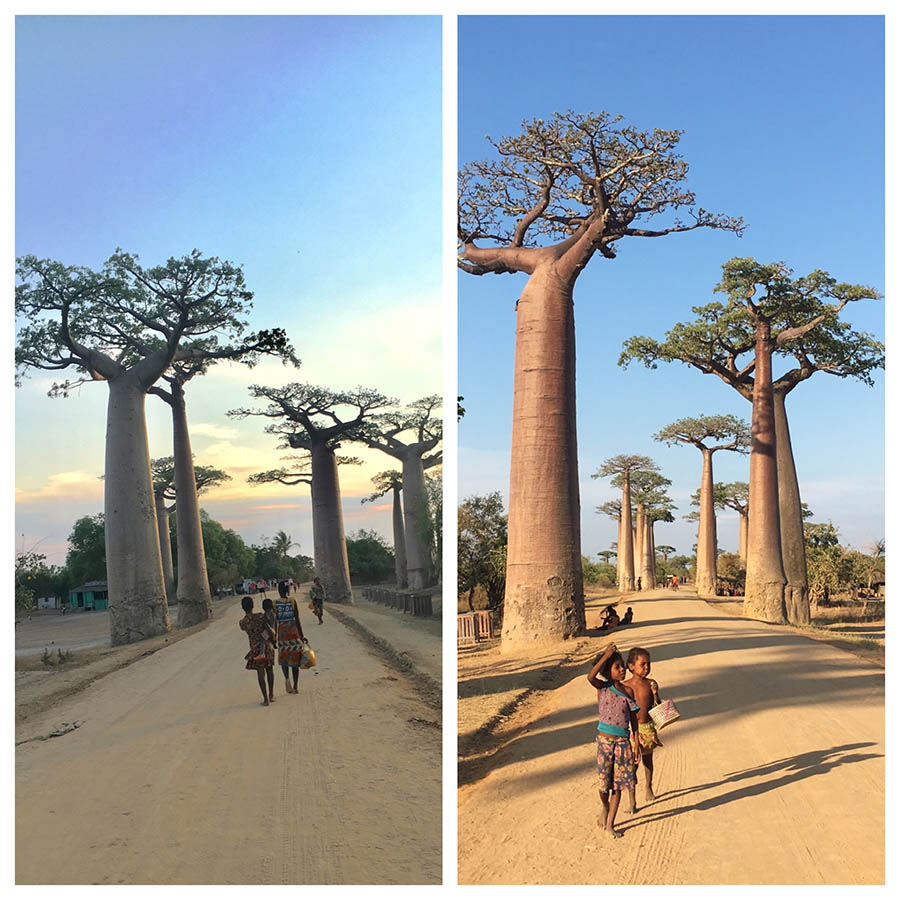

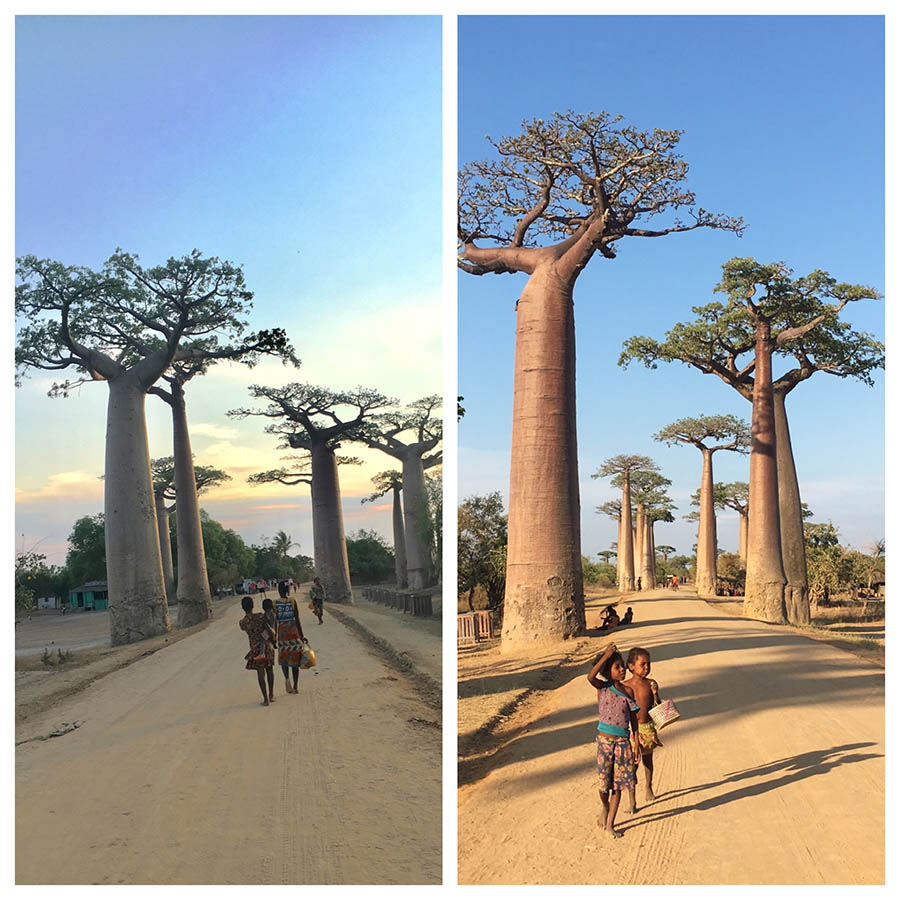

The Avenue of Baobabs in Morondava

Got More Than Expected – Literally

Given the situation with the plague, which was raging in the larger cities at that time, we decided to pay off the remaining car rental balance upon our arrival to Tana and leave for our 13-hour long non-stop drive west to Morondava as soon as possible. To spare us a trip through a chaotic street scene of the capital to the office, Anja sent Clio (his wife and a business partner) straight to our Airbnb with the car rental contract and last minute travel instructions (and to collect the remaining car rental payment in cash. Cash is KING in Madagascar).

The biggest surprise came when Cleo casually told us that instead of ONE English-speaking driver, we would get TWO guys for the “price of one”. Apparently, they did not have one person who could do both. While this might not be a common practice (although we did read about similar occurrences after the fact), we now believe to have benefited GREATLY from having a driver AND a guide on a trip with us.

Our Malagasy Driver (Tony) and the Guide (Martin)

Our Crew and the Rental Car

Bright and early next morning, Tony (our Malagasy-speaking driver) and Martin (a talkative English-speaking guide) cheerfully showed up at the gate of our Airbnb. Still processing this unexpected doubling in “staff”, we loaded our suitcases into an aged but sturdy-looking 4×4 dark-blue Hyundai and crawled onto the backseat. The longest leg of our journey across the island was ahead of us.

Here, I have to tell you that we had to change rental cars 3 times (including an unplanned break-down along RN34, see below) during our 17-day trip across the country. The stretch of the road along the west coast of Madagascar between Morondava and Tsingy Bemaraha National Park is considered to be a “vulnerable route”. And this is not ONLY due to the rugged terrain and treacherous driving conditions (which turn impassible during the rainy season).

Road between Morondava and Bekopaka (Tsingy Bemaraha)

Most tourists we met on the West coast of Madagascar were traveling in “convoys” of several cars. The “resort” in the Kirindy Private Reserve, where we stopped overnight for wildlife watching in a unique dry deciduous forest, had several local guards equipped with rifles at each corner for guest protection.

Not surprisingly, our car rental company had a prior arrangement with a local Sakalava driver (Lo-Lo), who replaced Tony (the driver who brought us to the West coast from Tana) in Morondava. Originally from the village of Belo, Lo-Lo was now living in a solid-looking house equipped with a large satellite dish along the main street of Morondova. He had the advantage of being intimately familiar with the route to Tsingy (which was nothing more than a rugged single track clay-colored dirt road) and the people living along the way. He had a sturdy high-clearance 4WD dusty Nissan with local registration plates, which would serve us well during the next 5 days in this “wilder” corner of Madagascar.

Road to Tsingy Bemaraha National Park

The Long Haul Across the Country on RN34

Traversing Madagascar from east to west and back were the most dreaded parts of our journey (9-12 hours each way). Although it ran along a largely paved RN34, many stretches were tortuous and rough, with regular deep potholes and washouts, often time without any shoulders.

Needless to say, there were no amenities along this route and whenever we stopped for 5 minutes breaks, we did not expect any privacy as there are people walking around ALL THE TIME. We were told to bring “white gold” on the trip with us. What is “white gold”, you would ask? Try toilet paper!! Most villages we passed along RN34 do not have any electricity and with many people on foot and livestock walking on the road, driving became especially hazardous in twilight, closer to the sunset.

2 hours into our 9-hour long drive on the way back from Morondava to Antsirabe, our car suddenly broke down in the middle of nowhere. It was late morning, but the temperature already was creeping into the uncomfortable high 30s Celsius. After spending one hour in the open sun (it was even hotter inside the stalled car) we started worrying about the prospects of getting stuck there. Aborting our trip and going back to Morondava seemed the best option at the time.

Fortunately, our Tony was able to contact our other driver Lo-Lo in Morondava, who came over flying in his car (our generous tips the night before probably helped A LOT there), and drove us all the way non-stop to Antsirabe. Once again, we counted our blessings and felt lucky to have rented a “car with a driver”. Our trip itinerary was salvaged!

The Car Breakdown on RN34

Navigating the Streets of Tana and Antsirabe

Although the roads within and around the larger cities, such as Antananarivo and Antsirabe were generally in a better condition, they were ALWAYS crowded. People were busy walking, selling and buying goods and just socializing.

Two-wheeled carts drawn by zebus or bullocks are still common sights on the roads of the highlands, especially around the cities and on market days. The rickshaw and the pousse-pousse, as it is called around there, are ubiquitous in the larger cities. And in Antsirabe, they seem to be a preferred mode of transportation. Throughout our trip in Madagascar, we experienced countless slowdowns to a crawl, traffic jams and hazardous driving situations in the densely populated area. All were masterly navigated by our expert driver(s) with a great deal of wisdom and patience.

Streets of Antananarivo in Madagascar

Driving RN7 through the Central Highlands

Traditionally, the best developed exchange economy and, therefore, the best road system in Madagascar has been located in the Merina and Betsileo sections of the central highlands, south of the capital. RN7 remains the most popular route for tourists due to its relatively good driving conditions. However, do not expect the quality even remotely close to what you would experience in Namibia and South Africa.

Sense of Privacy vs Sense of Place- When you Rent a Car with a Driver

As most independent travelers, who contemplate a car rental with a driver-guide, we had valid concerns about our privacy (or lack of thereof) during our trip. At the end of the day, we concluded that it was a small sacrifice we were glad to have made. Tony and Martin were so much more than a driver and a guide for us. They were our guardians, travel companions and entertainers, who did everything in their power to make our trip safe, comfortable and memorable.

In fact, next time we rent a car with a driver, we will definitely consider hiring a duo again as it has many advantages relative to a modest increase in cost (mostly in tips). By having both a driver and a guide, we could keep our belongings and the rental car under supervision at ALL TIMES and have a translator/interpreter accompanying us at all sites of interest, including banks or local village markets. We could rely on Martin making phone calls and hotel reservations for us “on the go”, while Tony (or Lo-Lo) was taking care of the driving.

When it comes to the time off-the-road, it was entirely up to us how much privacy we had. On several occasions, we did invite Tony and Martin out for drinks and dinner. Otherwise, we would agree on a time to meet on the following morning or afternoon and retire to our room for the rest of the day. There were simply no written rules in the contract on that sort of thing.

You’ll figure it out as you go. Keep it simple and enjoy the ride from the passenger seat of your rental car!

by mytravelcurator | Sep 15, 2019 | Central America, Costa Rica

What makes Wilson Botanical Garden worth a visit?

While planning our second trip to Southern Costa Rica, we stumbled upon “A Short History of Las Cruces Research Station and the Robert and Catherine Wilson Botanical Garden” written in one of the recent issues of “Amigos”, a semi-annual bulletin of the Las Cruces Biological Station. This insightful and entertaining article about the Wilson Botanical Garden’s origins and humble beginnings was written by Gail Hewson Hull, a passionate naturalist (here is her Foto Diarist blog) with close ties to the San Vito community and a former Director of Development and Visitor Services at the Biological Station.

Rio Java forest trail

The fascinating story, the vast collection of native and exotic tropical plants and the access to a large network of hiking trails through the primary and secondary forests, all make this 60-years old Botanical Garden and the Las Cruces Biological Station a major destination in the area. On our way to the Osa Peninsula, we decided to make a slight detour and spend a few days in this remote location by the Panamanian boarder.

The Special Mission of Tropical Botanical Gardens

The Wilson Botanical Garden may well be one of the most important botanical gardens in Latin America, and globally. A recent study “Ex-situ conservation of plant diversity in the world’s botanic gardens” by the University of Cambridge revealed that botanical gardens are predominantly located in temperate climate zones. However, an estimated three quarters of species absent from living botanical collections are, in fact, tropical in origin. These findings underscore the importance of the tropical plant collections, like the Wilson Botanical Garden, for conservation of floral biodiversity.

An Orchid near Casa Wilson

Wilson Botanical Garden’s Conservation Ecosystem

The Wilson Botanical Gardens and Las Cruces Biological Station are located near San Vito (300 km/6 hour drive) south of the capital San José) in the remote municipality of Coto Brus bordering Panama. This is a charming settlement with enduring Italian roots (Italian is still being taught at public schools here!). The town was founded in the late 1940-s by a group of “pioneers” attracted from Italy by the prospects of coffee growing in the area.

Situated on 10-hectares (~ 25-acres) at the elevation of 3,900 ft (1,200 m) above sea level within the Fila Cruces coastal mountain range, Wilson Botanical Garden boasts over 3000 plant species and one of the largest collections of palms in the world (over 600 varieties). The Biological Station and the Garden contribute to the AMISTOSA Biological Corridor, which connects the Osa Peninsula and the La Amistad International Park (PILA) in the Talamanca Mountains. Due to its proximity to La Amistad and incredible biodiversity, Las Cruces and Wilson Botanical Garden were declared a part of the Biosphere Reserve by UNESCO in 1983.

Examining the local tree cover changes over the recent 60 years, it becomes painfully clear that the Las Cruces Biological Station and Wilson Botanical Garden represent a green oasis in this largely deforested territory of Southern Costa Rica.

Early Days as a Private Garden and Commercial Nursery

The property was purchased in 1960 by horticulturist and tropical plant aficionado Robert Wilson and his wife Catherine. Somewhat ironically, Wilson Botanical Garden was initially created as a private botanical garden (with visitors in mind) and commercial nursery (for income). There was even an early attempt to cultivate tea for sale, which did not pan out in the coffee-growing community of San Vito.

The Centerpiece-Bromeliad Hill Garden

Garden’s Layout and Plant Collection

The world-renowned Brazilian landscape designer Roberto Burle-Marx, who was called “the Picasso of landscape design” for his artistry, and had a disciplined knowledge of botany, and provided the initial garden design concepts and several plants (some of which are still a part of the current collection).

“Any country which maintains such a Botanical Garden as this must be proud of its contribution to culture and education”

Roberto Burle-Marx, Rio de Janeiro, March 24, 1977

The Wilson Botanical garden harbors a vast collection of native and exotic plants from all over the world with a strong emphasis on Palms (Arecaceae), Bromeliads (Bromeliaceae), and other ‘showy’ cultivated families such as Heliconias (Heliconiaceae) and Gingers (Zingiberaceae and Marantaceae).

By design, the Bromeliad Hill and other central areas of the garden are heavily “manicured”, whereas some of the more peripheral areas are maintained in a more natural semi-wild form, blending well with the surrounding forest. This map of Wilson Botanical Garden shows its layout and the locations of different plant collections.

Visitor Information Area

On the hillside between the dining hall, the library and the reception building across from the parking lot, you will see eight large panels within the recently constructed Visitor Information Area. This colorful interpretive display is the work of artist Deirdre Hyde, who has created similarly impressive decorative and educational pieces for several other national parks in Costa Rica. The original art of the exhibit blends with traditional indigenous patterns and takes you through the history of the Coto Brus region and Las Cruces Biological Station, the adventures of early settlers. The scientific content focuses on plant collections of the Wilson Botanical Garden and nature conservation.

Palms

Wilson Botanical Garden’s palm collection, one of the largest in the world, is its pride and, as one palm expert put it, “the backbone of its beauty and elegance”. From about 2600 species comprising this large family (Arecaceae or Palmae, not to be confused with cycads or even cyclanths!), about 90 are native to Costa Rica.

There is no separate area for Wilson Botanical Garden palm collection, which now covers over 600 different varieties. Instead, you will enconter palm trees growing nearly on every corner: from the Ruffled fan palm (Lacuala grandis) in the Bromeliad Hill Garden to the giant King Kong Fishtail Palm trees (Caryota gigas) towering over the lookout (the Mirador). Within the Banana section of the Garden, we found a larger group of Costa Rica-native walking palms or cashapona (Socratea exorrhiza) standing on peculiar stilt roots. Climbing the Canopy Tower opened the view over the iconic Pigafetta palms silhouetted against the sunset or simply the blue sunny sky.

On the way to the greenhouse back in the garden, we spotted a sizable Traveler’s Palm (Ravenala madagascariensis), a national tree of Madagascar. Despite its name and some resemblance, this remarkable plant with banana-like leaves, is not really a palm tree. It is a relative of the South African “bird-of-paradise” plant family and is believed to use non-flying mammals such as nectar-feeding lemurs for pollination.

Giant King Kong palm trees

Bromeliad Hill Garden

Surrounding Casa Wilson, which recently underwent significant repairs after 50 years of sporadic damages by weather and termites, there is the terraced Bromeliad Hill Garden. It has been the centerpiece of the “formal” part of the Wilson Botanical Garden, ever since Burle Marx visited Robert and Catherine Wilson during the “conceptual design” phase in 1962. Follow the grassed path down the Bromeliad Hill, and you will walk past two of his signature plants, the ruffled fan palm and the massive imperial bromeliad (Vriesea imperialis).

The Pollinator Garden located behind the arid plants collection on Bromeliad Hill is one of the more recent additions, which was initially designed as a Hummingbird Garden. Later it was cheerfully “re-branded” and populated with mostly native plants growing in a concentric pattern around the old water fountain that was originally installed by Robert Wilson near the Wilson house. This flowering display is a living and breathing magnet for local bees, butterflies, hummingbirds and other nectarivores (such as beetles and bats).

Cycad Section at Wilson Botanical Garden

Cycads

There is a small thriving collection of Cycads from around the world just behind Casa Wilson: Cycas from Asia and Australia, Dioon spp. from Mexico and South America and a few African Encephalartos. We also spotted the Costa Rica’s native Zamia fairchildiana displaying spectacular cones of both types. If you venture out to the primary forest trails at Las Cruces Biological Station, you might run into much larger samples of this cycad (like this over 10-foot tall Zamia fairchildiana plant photographed by the late Wilson Botanical Garden director and renowned Costa Rican botanist Luis Diego Gomez https://fotodiarist.com/2016/07/02/finding-at-las-cruces-the-impartial-calm-of-nature/. Learn about all other Zamia species growing in Costa Rica here.

Orchids

While orchids are not a specialty of Wilson Botanical Garden, you can still find quite a few orchids throughout Las Cruces Biological Station. At least 130 orchid species have been identified within its boundaries by Fabián Alb. Sibaja Araya. Descriptions and photographs of over 50 different genera are part of this illustrated inventory of its orchidaceous flora Orchids of Las Cruces Biological Station. For orchid aficionados, I would recommend a trip to the Lankester Botanical Garden in Cartago, near San Jose. It has a vast Orchidaceae collection and is credited for its prominent role in tropical orchid research and conservation.

There are a few orchids with large showy inflorescences growing just behind the Cycad collection. In the Banana area, we spotted elegant Scaphyglottis mesocopis (a native orchid of Costa Rica and Panama) growing around a tree trunk (these are blossoming between Jan-Mar and Nov-Dec).

Native Orchid Scaphyglottis mesocopis

Heliconia Display

The Wilson Botanical Garden’s heliconia collection is a short walk down the hill from Casa Wilson. The layout and design of the Heliconia Garden have been completely overhauled in the recent years. The Heliconia plant collection has also been expanded and currently covers over 100 species and varieties (of roughly 220 species spread throughout Central and South America and some Pacific Islands) of these majestic neotropical plants with showy flowers. This section of the Garden dotted with colorful splashes of erect and pendant heliconia inflorescences are frequented year around by local hummingbirds.

The Mirador and Las Positas Water Garden

The far corners of the Garden, like the Mirador and the Water Garden, can be easily overlooked. Surrounded by giant King Kong palm trees, the Lookout is a perfect spot for getting a sense of garden’s elevation and for taking a power nap on a late afternoon.

On the way back from the Mirador, we made a right turn into a path zig-zagging through the giant Bamboo “forest”, which was planted by Robert Wilson some 40-45 years ago. Hidden from the plain view in a shaded valley decorated with a natural water pools and benches, was the newly created Water Garden. This divine spot in the garden was just recently reclaimed from a prolonged “occupation” by invasive species, such as Velvet Pink Banana (Musa velutina) and Beehive Ginger (Zingiber spectabile) vegetation and repopulated by Costa Rican native wetland and aquatic plants. Since its inception, the water garden became one of the favorite spots for local birdwatchers.

Las Positas Water Garden

How Much Time to Spend?

Although Wilson Botanical Garden is relatively compact and most of the plant collections can be covered in a single morning or afternoon, one should plan to spend at least one whole day (the Garden is open between 8 am and 5 pm) for more than a cursory glance. This should give you enough time to climb the Canopy Tower and even take a short hike (~2 hours) along the Rio Java trail (one of the numerous hiking trails through the primary and secondary forest which are maintained by Las Cruces Biological Station). Or you could just take it slowly and do some heavy relaxing now and then in the shade of the canopy. Bliss …

by mytravelcurator | Jul 20, 2019 | Central America, Costa Rica

On the latest trip to Southern Costa Rica, we spent a few days botanizing along the trails of Matapalo Beach on the remote Osa Peninsula. Experienced local nature guides from the Lapa Rios Ecolodge taught us how to recognize some of the area’s most remarkable plants and trees and to appreciate Costa Rican rain forest’s medicinal bounty. Planting a “suicidal tree” at the end of the stay felt like a tiny contribution to this last stronghold of the Pacific rain forest.

“A traveler should be a botanist, for in all views plants form the chief embellishment”

Charles Darwin

Matapalo – What’s in the Name?

Matapalo is a local name for strangler fig (Ficus species) and on Osa Peninsula these trees are a rather common sight. A large number of local birds and some animals feed on ficus fruits and spread around their seeds. Of the 150 Ficus species living in America, many (if not most) have so called “strangler habit”. On Osa Peninsula, you are likely to encounter Ficus obtusifolia and Ficus nymphaeifolia, “hugging” other trees. The host tree eventually dies by shading, trunk constriction and root competition. However, “strangling” is rather common growth strategy in tropical lowland rain forest and cloud forest and is not at all limited to ficus trees. In some areas of rain forest, as much as 15% of canopy trees is estimated to host stranglers and similar hemiepiphytes.

Matapalo – Strangler Fig

Botanical Resources for Osa Peninsula Flora

To fully appreciate plant diversity in this corner of Costa Rica, check out Vascular Plants of the Osa Peninsula, Costa Rica website. This collection contains a comprehensive “check-list” representing 2240 species, 950 genera, and 167 families with sighting maps of thousands of local plant records. A more compact illustrated field guide compiled by local and visiting (from the Missouri Botanical Garden) botanists offers images of ficus spp. and other charismatic plants from the Moraceae family, which you are likely to see on Osa Peninsula.

Guided Botanical Tours on Matapalo Beach

To learn more about the unique flora of the region, we signed up for a couple of local hikes with Lapa Rios. This is one of the National Geographic’s Unique Ecolodges, which has access to several miles of privately owned trails cutting through the primary and secondary wet lowland rainforest. Most importantly, they graciously allows travelers who are not staying at the lodge on their trips if spots are available. Otherwise, you can also arrange for rather affordable private tours with their nature guides.

The Medicine Walk on Osa Peninsula

During our one-week stay in Cabo Matapalo, we had no problems signing up for several of their small-group nature walks (they can include up to ten people, but most had three to five). To learn more about the captivating history of Lapa Rios and its environmental mission, check out this post about the “Pigs, Twigs and Garbage Tour”.

The Medicine Walk

For the last 30 years, Costa Rica has been actively involved in “bioprospecting” of its botanical riches. The purpose of which has been to identify and screen plants for medically active compounds in search for yet undiscovered medicines. At that time, it was estimated that about 10 % of plants tested on the basis of documented traditional medical use contained therapeutically active agents in commercial amounts. Of these, 10 % will exhibit unique medicinal effects. This odds ratio of 1:100 is strikingly higher than the effectiveness of a typical all-synthetic screening program estimated at 1:23,000. Back then, it was estimated that about three-quarters of plant-derived drugs were discovered through folk usage.

To learn about the local ethnobotanical traditions, we signed up for a 2-hour Medicine Walk with Jeffery, a local guide from Lapa Rios. We started this highly interactive short hike (the Medicine trail itself is only 1 km long) in a small garden right behind the main lodge.

“Baby Powder” Plant

Equipped with “Medicinal Plants of Costa Rica“ book, Jeffery brings our group of five to a patch with lavishly growing Calathea lutea (the common Spanish name is Bijuaga). These large-leaved herbaceous plants are from a pan-tropical Marantaceae family with over 60 different Calathea species described just in Costa Rica (one third of which are endemic or regional endemic). They are also common in the understory vegetation of the wet lowland rainforest on Osa Peninsula and several species are local endemics.

The wax covering the silvery-white undersurface of Calathea has been used by locals as a talcum substitute in baby care and a general-purpose lubricant. The indigenous peoples have also adopted it in the “curing” or waterproofing of bowstrings, in basketry. With a few gentle strokes of a pocketknife, Jeffery scrapes off a heap of white powder from the shiny undersides of a leaf. The average yield of wax from large-leaved species, such as C. lutea can be as high as 0.7 gram per leaf!

Collecting wax from Calathea lutea leaves

Carpenter´s Bush – a Lady Medicine and More

Here is something else. Justicia pectoralis, locally called as “tilo or carpenter’s bush”, is another medicinal plant with a long history of traditional use. In Costa Rica, leaf extracts are sold as an over-the-counter sleep aid, whereas on the markets, dried plants are advertised as a treatment for menopause and other “lady ailments”. In addition to its mild sedative and estrogenic qualities, it is also believed to have anti-inflammatory effects.

Follow the Medicine Trail of Rain Forest

After spending half an hour botanizing on the grounds of the ecolodge, we took a short ride to the head of the Medicine Trail and started our hike in the rain forest. There were “discoveries” on every corner. We paused briefly by a Jackass bitters (Neuroloena lobate). Resembling our ordinary ragweed, this plant is used as a natural remedy against intestinal parasites, for acid reflux or indigestion and, as a tonic for traveler’s diarrhea.

Next in line was a “spiral ginger” plant Costus spp. (from Costaceae) with its deep-green leaves forming a neat spiral. Although few docs believe in its anti-lithic magical properties, the plant has been used as a traditional medicine for kidney stones and other ailments of the urinary system. Ethnobotanical fancy aside, Costus represents a very interesting diverse group of Osa Peninsula plants. Originally (millions of years back) from Africa, this family is now counting over 100 mostly neotropical species. A dozen different Costus species, including several regional and Osa Peninsula endemics (such as C. osae, C. ricus and C. stenophyllus), were reported by David Skinner in the Golfo Dulce area. Interestingly, the majority of the locally growing Costus have evolved as Ornithophilous species, which means that they are pollinated by hummingbirds as opposed to bees.

A leaf of Wild Costus or Spiral Ginger

Our next stop along the trail is a massive Kerosene tree (Hymenaea courbaril, also called stinking toe), which can reach the height of 150 feet and more, supporting its crown with a large trunk. Jeffery makes a tiny cut through its bark, letting a drop of sap run down the blade before setting it on fire. The highly flammable ‘fragrant’ resin is believed to defend this neotropical native tree against insects, herbivores and pathogenic fungi. This sticky gum has been used by locals as an anti-itch and anti-mosquito remedy. Already in the Pre-Columbian time, it was collected by the aborigines of Costa Rica and Panama and used as incense, varnish, and for carving amulets.

Arboreal Wonders of the Primary Rain Forest

Next day we continued our botanical explorations (this time with Edwin, see a very short video from the hike) on the Osa Trail, which is over 3 km long, but is largely downhill or flat. It covers areas with old secondary growth as well as the original primary rain forest with magnificent native trees, many of which are several hundred years old.

Primary Rainforest Canopy

Less than half of the remaining forest on Osa Peninsula is old growth, but the region still has an astounding plant diversity and some tallest trees in Central America. 5% of the tree species are endemic and a as much as a quarter of as regional endemics, growing only in Panama, Costa Rica and Nicaragua.

Edwin introduced us to a native Diesel tree (Copaifera camibar), which produce resin similar to that of the Kerosene tree, a majestic Mahogany (Carapa guianensis) and an Abrojo (a vernacular name of Sloanea spp) with a high buttress hugged by lianas. The lush-green understory of the rain forest was occasionally dotted by the splashes of red Passionflower vines (Passiflora spp). In some areas along the trail, the forest floor was littered by yellow flowers of the giant Ajo or Garlic tree (Caryocar costaricensis). The blossoms give off The scent of these blossoms, which was reminiscent of garlic gave this regional endemic its name.

Along the trail, we also got a good look of a wild Theobroma cacao, which the indigenous peoples of the Central America, such as Maya, Toltec and Aztec, turned into “food of the gods” before sharing it with the rest of the world. For a moment, we stopped and craned our necks by an old Ceiba and a Wild Cashew (Anacardium excelsum) trees towering over a steep hillside, to appreciate the share size of these giants, the tallest trees of the Osa Peninsula.

Wild Passion Flower

Planting a “Suicidal Tree” Reseco

After the botanical experiences in the woods, it seemed only natural to sign up for “Plant a Tree” (another “green activity” offered by Lapa Rios ecolodge). A symbolic, yet personally meaningful attempt to leave behind a positive mark in the rain forest, which we all found so “therapeutic”. Among the seedlings lined up at “the tree nursery” by the main lodge, the intriguing description of the “suicidal tree” reseco stood out. Crowned with just a few bright-green pinnate leaves on longer petioles, these baby plants looked rather unremarkable.

Edwin explained that reseco (Tachigali versicolor) trees are known for their unusual life cycle: they flower and produce seeds once in a lifetime, then shed their leaves and die. This mode of reproduction (monocarpy, from Greek monos (single) and karpos (fruit)) is very rare among long-lived trees. The remarkable natural history of this tree was first described 50 years ago by Robin Foster, an ecologist from the Fields Museum’s Environmental Conservation Program. He also discovered something else: the ubiquitous leaf-cutter ants never prayed on the “suicidal tree” before the flowering period. This is because the tree produced the defensive anti-fungal compound, whereas the ants relied on fungus as their food source. However, shortly after the fruits were produced and dispersed, the trees would get invaded by ants and other insects and succumb within a year. Not surprisingly, the indigenous people in the Amazon have traditionally used reseco leaf extract as an anti-fungal remedy. Reseco belongs to the pea (legume) family and is one of the regional endemics restricted to the Pacific lowland forest from Costa Rica to Western Columbia.

Planting a “Suicidal” Reseco Tree

One might ask why some trees became monocarpal and how they remained successful in the wild? Scientists, who have studied these trees, believe that monocarpism developed as an adaptive mechanism. Higher growth rate and earlier reproductive maturity might make up for the 100% mortality of adult reseco trees after a single reproductive season.

Unlike majority of other tropical trees, reseco seedlings are shade-tolerant (and are more likely to survive because less grazing occurs in the shaded areas). They are more likely to survive growing under the canopy of trees from the same species, but can also survive for many years in the understory of other trees while waiting for a gap in the canopy to emerge. Based on this knowledge, we decided to give it a shot and planted the young reseco tree in secondary forest with gaps in the canopy. Keep our fingers crossed.

by mytravelcurator | Jun 16, 2019 | Central America, Costa Rica

Osa Peninsula is a wildlife paradise and a magnet for naturalists around the world. Whether you are a casual birdwatcher (like us) or a hard-core birder with a long list of “lifers”, the charismatic avifauna of this remote corner in the Southern Costa Rica will not disappoint. Below is a brief recount of our “semi-organized” bird-watching experiences around Matapalo Beach on the southeastern tip of the Osa Peninsula.

On a recent trip to Southern Costa Rica, we used every opportunity to explore local bird communities of the areas we visited. Two of the most recent bird-watching highlights include Los Cusingos Neotropical Bird Sanctuary (founded by Alexander Skutch, a prominent American botanist-turned-ornithologist) and the Resplendent Quetzal Tour to the cloud forest of Las Tablas Protected Area.

The last week of that vacation was spent on the remote Osa Peninsula, and, naturally, birdwatching was on our “to-do-list”. The Osa Peninsula bird list (compiled by Osa Conservation) is long, with close to 400 different species (see some Osa Peninsula bird pictures here). Being “opportunistic” birdwatchers, we opted for one guided tour with Lapa Rios Ecolodge, leaving the rest in the hands of karma and pure luck. Want to know how we did? Read on.

A Red-Lored Parrot couple in a palm tree

Birds around our Matapalo Eco-Villa in Lowland Rain Forest

Our solar-panel-powered Airbnb rental “villa” was in a secluded area, in between the beach and the main road. Surrounded by a garden with pineapples, banana plants and coconut palms, it attracted plenty of frugivorous birds such the Yellow-throated Toucan, the Fiery-billed Aracari and the Red-lored Parrot.

In addition, sizable troupes of White-faced Capuchins and Squirrel Monkeys were descending on the property every afternoon to gorge on bananas, coconuts and flowers. And where there are squirrel monkeys, there are their air-born predators. We spotted both Common Black Hawks and Roadside Hawks, hiding in the lush-green vegetation and waiting watchfully for a lucky break.

Watchful Common Black Hawk

In each group of Squirrel monkeys, all females synchronize their birthing time to a single week in February-March to minimize the loss of newborn babies to these birds of prey. You can find more interesting facts about our observations of all four species Costa Rican Monkeys in Matapalo Beach in my other post on the subject.

The Coastal Birds of Matapalo Beaches

Every morning, rowdy Scarlet Macaws (Ara macao) were patrolling the beaches of Matapalo. Nuts produced by the abundant Beach almond trees (non-native species to these parts of the world) are among favorite foods of these large colorful birds. Osa Peninsula boasts one of the most robust populations of Scarlet Macaws in the Central America.

In low tides, when the volcanic coastal bedrock becomes exposed, one can easily spot wading birds, such as Spotted sandpiper and Ruddy Turnstone. You may even see more uncommon migrant shorebirds in the area. One morning, we observed a Semipalmated Plover running between the rocks and pausing periodically to peck on marine “crawlers”, worms and small mollusks.

Walking along any of the beaches around Cabo Matapalo, the omnipresent Brown Pelicans and Black Vultures were hard to overlook. High in the blue sky, we saw ominously dark silhouettes of soaring Magnificent Frigatebirds and, occasionally, King Vultures.

Black Vulture on Matapalo Beach

Birds of Rivers and Wetlands

While exploring the estuary of the smaller Carbonera River, we saw a Black-bellied Whistling Duck, Purple Gallinules and solitary Green Kingfisher and Ringed Kingfisher. White Ibises, along with Little and Great Blue Herons were right there, by the main road. The portion of the river close to the beach had a denser vegetation, quite suitable for a Bare-throated Tiger-heron and a few Yellow-crowned Night-herons with their juveniles. At the very end on the trail, by the ocean, our bird-guide alerted us to the presence of a Least Sandpiper feeding in shallow waters.

Pastures and Roadside

As we were wandering along the main road, the sightings of Cattle Egret and Snowy Egrets were common in the cleared areas with grazing cattle. Yellow-eyed Great-tailed Grackles, and Great Kiskadee and Tropical Kingbird (both of which are common local flycatchers) are using fences, poles and vegetation by the roadside as launching platforms in their pursuit of flying insects.

There are a few trees with large shady crowns towering over the pastures. These are favorite hangouts and foraging places for noisy Crimson-fronted Parakeets and Orange-chinned Parakeets. Other birds you are likely to see here are Yellow-headed Caracara and Crested Caracara, opportunistic raptors mainly feeding on carcasses of dead animals. Red-crowned Woodpecker is also commonly seen in the area. On our organized bird-watching tour with Lapa Rios Eco Lodge (see more about this trip below), a our guide masterly spotted (and got it on a scope for us) a Spectacled Owl flying into a giant tree in the middle of the pasture.

One day, we spotted a curious pitch black-colored bird with a thick bill sitting on a fence pole with his head turned backwards 180 degrees. It was a Smooth-billed Ani from the cuckoo family, who has as a ‘habit’ to forage alongside the domestic cattle. Apparently, it allows these clever birds to take advantage of insects flushed by grazing animals. Costa Rica did not have native large grazing ungulates (such as deer, antelope and the like) before cattle had been introduced within anis’s natural habitat. Scientists believe that this feeding relationship with cattle evolved during the last 400 years (and became particularly strong during the last century).

Smooth-billed Ani on a Pasture

Migratory neotropical songbirds following their traditional routes between the wintering and breeding habitats must stop en route for foraging and regaining their strength. For many, Osa Peninsula serves as such a stopover refuge in the early spring and late fall. Late January-February are perfect for viewing migratory passerines along the Matapalo Beach.

The dead-end Matapalo Beach Road is quiet and much less trafficked (due to its rugged condition), without clouds of dust to deal with (which are inevitable on the dirt-gravel-covered “main road”). Early morning birding along this coastal road, which runs close to the beach, is excellent. It allows for a better visibility than overgrown rain forest trails. Here, you should have ample opportunity to see the most common small songbirds such as Spot-crowned Euphonia, Cherrie´s Tanager, Blue-gray Tanager, Palm Tanager, Buff-rumped Warbler, Tennessee Warbler and Yellow Warbler. On our early-hour walk to the King Louis Waterfall, we met a couple of small private birding tours with a scope-equipped guide scouting the roadside bushes.

Lapa Rios “Birding” Tours

Lapa Rios Eco Lodge has several bird-watching tours (check their tour book here), all of which are well-suited for the novice and more experienced birders.

One morning, we joined them on “Early Birds Tour”, which was an easy walk led by Edwin, a 24-year local veteran of the Lodge. He is a locally known wildlife expert and an active participant of several bird surveys and other targeted conservation efforts on Osa Peninsula. Our tour lasted around 3 hours and covered several typical local bird habitats.

Early Birds Tour with Lapa Rios

Over 300 bird species (see complete Lapa Rios Bird Checklist) live or migrate through the the area covering about 11 miles (19km) of the coastal Osa Peninsula between Cabo Matapalo to Puerto Jimenez (including the Lapa Rios Reserve itself). The Eco Lodge also has a late afternoon birdwatching walk and a 5-6-hour tour to the mangroves of the Rio Esquinas (with a great opportunity to see more bird species of the Pacific Coast Wetlands).

Rare Birds of Osa Peninsula in Matapalo

Several local bird species from the Red List (living in the area between Puerto Jimenez and Capo Matapalo) are fairly common: these are Baird’s Trogon (Trogon bairdii), Mealy Parrot (Amazona farinose), Great Tinamou (Tinamus major) and Yellow-throated Toucan (Ramphastos ambiguous). And we have seen most of these.

Other species from the “near-threatened” category, such as Golden-winged Warbler (Vermivora chrysoptera), Ornate Hawk-Eagle (Spizaetus ornatus), Crested Eagle (Morphnus guianensis), Marbled Wood-Quail (Odontophorus gujanensis), Great Curassow (Crax rubra) and Three-wattled Bellbird (Procnias tricarunculatus) have also been reported in the area but are rare.

Turquoise Cotinga (Cotinga ridgwayi) is another vulnerable resident bird species of Osa Peninsula, but it is a rather uncommon sight. We were lucky to observe this brilliantly blue bird while visiting the Los Cusingos Neotropical Bird Sanctuary (this location is apparently one of the best sites in Costa Rica to spot this species). For details, check out our post about a guided bird-watching tour at Los Cusingos while staying in Quizarra.

Osa Peninsula and Regional Endemic Birds

Black-cheeked Ant-Tanager, Yellow-billed Cotinga and Mangrove Hummingbird are three endangered endemic or regional endemic bird species from the Red List residing on Osa Peninsula.

Black-cheeked Ant-Tanagers (Habia atrimaxillaris) have the smallest distribution of the five known species of ant tanagers (Habia spp.) with current natural habitat restricted to about a 1,000 sq.km. of Osa Peninsula and Golfo Dulce. On Osa Peninsula, they are are widely distributed but its preferred habitat is “forest with closed canopy and forest edges” with possible affinity for “steep terrain”.

Yellow-billed Cotinga (Carpodectes antoniae), a close relative of Turquoise Cotinga, is an endangered and range-restricted species, with an estimated population of 250-999 (and decreasing). Yellow-billed Cotinga lives on the small remaining patches of the mangroves-rainforest interface on the Pacific Coast. It heavily relies on each of the habitats for food and reproduction, respectively. However, the area representing such a combination of ecological niches has been shrinking.

Mangrove Hummingbird (Amazilia boucardi, estimated population of 2,500-9,999) inhabits mangrove habitat (around 1,000 sq.km.) in a few separate locations along the Pacific Coast of Costa Rica. They feed on nectar produced by mangrove plants, such as Pacific Mangrove (Pelliciera rizophorae) and Hamelia spp.

Boat tour to Sierpe River Mangroves

Endemic Birds’ Ecology Surveys to the Rescue

Although the chances of spotting any of the three Osa Peninsula regional endemic birds are not particularly high, Black-cheeked Ant-Tanager and even Yellow-billed Cotinga have been observed in the area between Cabo Matapalo and Puerto Jimenez . Both species have been reported by the Lapa Rios’s nature guides in the past, although these sightings were rare. Inland sightings of Yellow-billed Cotingas “in small numbers along the Rıo Tigre, 8 km upriver from coastal mangroves, between July and December” have also been reported in “Notes on the distribution, natural history and conservation of the Yellow-billed Cotinga (Carpodectes antoniae)”.

To support an effective management and conservation of regional endemic birds, Osa Conservation and local citizen-scientists and ecotourism business owners have been collecting and sharing knowledge about their natural history and reproductive behavior. Elizabeth Jones, a local naturalist and the owner of the Bosque del Rio Tigre Lodge, and other bird experts conducted several such surveys of the local endangered birds. “Ecology of Endemic Birds” covers the Osa Peninsula habitats of the Yellow-billed Cotinga, the Black-cheeked Ant-Tanager and the Mangrove Hummingbird.

On Osa Peninsula, Yellow-billed Cotinga is best spotted in Rincon de Osa (not surprisingly, this is also the location of the recently established Yellow-billed Cotinga Sanctuary (read its story here“The Yellow-billed Cotinga Sanctuary Takes Shape”) and the mangroves of the Rio Sierpe, Rio Esquinas River and Rio Coto (best accessed by boat). Although inland sightings of this bird were reported (e.g. near Puerto Jimenez) in the past by the Lapa Rios Lodge (Matapalo), these locations (as mentioned above) are not typical. A boat trip through the mangroves the Terraba-Sierpe National Wetlands will most likely produce sightings of Mangrove Hummingbird and its other more common relatives, such as Rufous-tailed Hummingbird and Charming Hummingbird.

If the endemic birds are on your “target list”, hiring local bird experts from the Osa Conservation or Bosque del Rio Tigre Wildlife Sanctuary and Eco Lodge (with its impressive bird list on its own), who are intimately familiar with these birds’ remaining “strongholds”, would probably be your best bets. Good Luck!

by mytravelcurator | Jun 8, 2019 | Central America, Costa Rica

During our recent trip to Southern Costa Rica, we eagerly joined the “Twigs, pigs and garbage” (aka Sustainability Tour) at Lapa Ríos. Perched on a hill over the Matapalo Beach on Osa Peninsula, this ecolodge runs this special 2-hour walk to educate its guests and other local visitors about “true green” hospitality combined with environmental protection. It also reveals a fascinating story of an ordinary American couple on their quest to save a unique forest and to support local livelihoods.

Our Walk Guide

On a hot and sticky January afternoon, our small group of 4 travelers from New England met at a shaded gazebo. There we were greeted by Clare, the only non-native employee of the lodge at the time. A Florida University biologist in her gap year and aspiring environmental lawyer, Clare shared a few captivating stories about Lapa Rios, its humble beginnings and the ambitious mission.

Meeting our Tour Guide

Lapa Rios Founders – An American Couple on a Mission

The story of John and Karen Lewis, the Lapa Ríos founders was downright enthralling. In the early 90s, this American couple (a lawyer and a music teacher, both long-time Peace Corps volunteers) sold all their possessions and “raided” their retirement and profit-sharing funds. They soon settled down in a run-down hut on the newly purchased 1000 acres of primary forest on the remote Osa Peninsula in Costa Rica.

In an interview recorded for the 25-year anniversary of the Lapa Ríos ecolodge in 2018, Karen talked about the turbulent start, current challenges and future aspirations of this several-decade long project. She also spoke of the succession plan and how important it was to make sure Lapa Ríos stayed on its mission of protecting the last stronghold of the Pacific lowland rainforest in Central America. To read this interview in-full, check out the Earth Changers website.

A Success Story of Costa Rican “Green Tourism”

Costa Rica prides itself on being a green tourism destination. Nature tourism became a part of Costa Rica’s development policy in the 1970s and 30 years later it became the largest industry in the country. Since then, the “ecolodge-style” hospitality businesses quickly mushroomed throughout Costa Rica. However, their true nature as well as environmental and social impacts on local communities remain controversial. You can read some critical opinions in “Buying Up Nature: Economic and Social Impacts of Costa Rica’s Ecotourism Boom”, if interested. Still, even the skeptics seem to agree on Lapa Ríos Ecolodge’s remarkable success story.

CST Rating and National Geographic Society “Badge”

Back in 2003, Lapa Ríos was the first hospitality business in Costa Rica awarded the maximum 5 Leaf certification rating by CST (Certification for Sustainable Tourism) and it remained one of the few which pass this high bar during regular on-site audits.

The glamour of being the very first of the National Geographic unique Costa Rican ecolodges aside, Lapa Ríos must live up to its name. Delivering ecologically sustainable luxury in one of the most remote area of Costa Rica in no easy task. The Sustainability Tour which takes place on the ecolodge’s grounds offers a glimpse into behind-the-scene operations that make it possible.

The Man Behind the Main Lodge and the Mission Statement

After receiving the thorough introduction, we moved to the Lapa Ríos Main Lodge. Its architect, the late David Lee Andersen, was also a visionary of ecologically sustainable tourism and a long-time friend of Karen and John Lewis. He was also the man who coined the ecolodge’s original long-standing mission statement:

“No matter how you cut it, a rainforest left standing is worth more”

In addition to the eye-pleasing and airy design of the lodge, its “thatched roof” (which looks amazingly authentic) is NOT made of quickly decaying high-maintenance natural materials. It is produced from durable recycled plastic.

No Plastic Straws at Lapa Rios Bar

At the bar, well-stocked on liquors and non-alcoholic beverages, you won’t see any cans or plastic bottles. Plastic straws have also been replaced with elegant locally crafted bamboo stalks. All guests at Lapa Ríos are supplied with a reusable thermos filled with potable water and mounted into knitted poaches.

The Kitchen, Organic Garden and Compost

We move into the kitchen, were the gourmet meals are made to order daily, using locally sourced ingredients whenever possible and by-passing long-term storage. All of organic waste, including the food scraps from the meals, is manually sorted and either fed to the pigs or locally composted.

Pigs and Methane Gas

Happy Pigs of Lapa Rios Ecolodge

You are unlikely to meet the piglets and the “power house” they support while they eat your meal leftovers, unless you join the Sustainability Tour. We had to take a short drive to the service entrance of the ecolodge to see the pigpen, the compost area and other related housekeeping facilities.

The small vegetable garden had organically-grown pungent wild coriander along with other herbs and veggies. Next to the patch, there was a compost heap, which remained an ongoing project. The ecolodge continued to experiment with the best ways to degrade various types of organic materials, much of which is acidic.

Nearby, there was a small-scale roofed pig-parlor. Inside an airy enclosure, we found a dozen young hogs seemingly content, though making occasional grunts: “They must have just been fed”, Clare commented with a smile.

In addition to reducing food waste while “growing meat”, the capture and utilization of greenhouse gas methane the pigs generate has other ecological benefits. Through anaerobic digestion, this “low-cost system” of methane production creates renewable energy. Instead of burning firewood, propane or electricity, the low-cost biodigestors (see photo below) produce high-quality biogas, which is used for direct heating or for running a generator to create electricity for any other purpose.

Biogas Production from Pig Manure

Preserving Unique Wildlife of Osa Peninsula

During the tour, we learned that Lapa Ríos is not only committed to being a highly sustainable hospitality business. It is also a nature reserve with multiple ongoing projects, involved in direct wildlife protection. From its early days, the ecolodge has been expanding and improving natural habitat for the growing population of the unique Osa Peninsula fauna and flora.

The property is an integral part of the protected area and additional habitat for the wildlife “spillover” from the Corcovado National Park. Check out some of the images of these animals, including the endangered ones, such as puma, ocelot and paca, captured by the motion-activated cameras installed throughout the Lapa Ríos Nature Reserve.

Motion-activated Camera for Wildlife Surveys

The lodge’s impact on local environmental protection is reaching far beyond its borders. Reportedly, a salaried ranger position in the neighboring Corcovado National Park has also been supported by Lapa Ríos.

The Social Impact of Lapa Ríos Ecolodge

But protecting the nature and the livelihoods of local people at the same time is a tricky balance. For the founders of Lapa Ríos, the social aspect of the enterprise has been an important part of their “business model” and it continues giving back to the community in many ways.

Already 10 years ago, a group of scientists from Stanford University took a closer academic look at the “case of Lapa Ríos”. Through interviews, questionnaires and “before and after” forest cover comparisons they gauged the environmental and socioeconomic impact of the ecolodge on the local communities and rainforest conservation on Osa Peninsula. Their findings were made public in “Social and environmental effects of ecotourism in the Osa Peninsula of Costa Rica: the Lapa Ríos case”.

Giving Back to the Community

Many Costa Rican hospitality businesses make use of seasonal guest workers due to the natural swings typical for tourism industry. At Lapa Ríos you will meet over 70 full-time staff employees, most of whom are local to Osa Peninsula. Several nature tours we took through the lodge were guided by the local “veteran” Edwin, who has been working at the ecolodge for over 20 years.

In addition to direct support of nature conservation personnel within and beyond its borders, the ecolodge is also offering “Nature guide training” cources to anyone interested in becoming a part of Costa Rican green tourism.

Other programs at Lapa Ríos (such as “Dock-to-Dish” initiative) are committed to provide fresh locally-sourced food and other necessary sustainable materials for the ecolodge as well as stable well-paid jobs to the local fishermen, farmers and other small business owners.

Organic Long-leaf Coriander at Lapa Ríos

Investing into the Future

In the early days, all local kids in the area could only receive a few months-worth of schooling per year because the roads to the nearest school in Puerto Jiménez remained impassable most of the time. Nowadays, they are offered year-around education at the local Carbonera school established by the founders of Lapa Ríos. With continuing financial and social support, the former students are now working as teachers at the school and the virtuous cycle continues …