by mytravelcurator | Oct 28, 2019 | Africa, Madagascar

Renting a car without a driver while traveling in Madagascar is possible and perfectly legal, but rather uncommon. And there are many good reasons for such a consensus among travelers. Before hitting the road, you can read about our experiences with Malagasy roads and driving conditions. Below, we share our thoughts about booking a rental car in Madagascar and what to expect from spending many days in a company of complete stranger(s) (your personal driver–guide, that is).

First, let me point it out – we love self-driving while on vacations. No other way of travel offers more flexibility and independence while travelling. There are places in the world, however, where driving around is just neither practical nor enjoyable. In our view, Madagascar is such a country.

Although a few intrepid souls still try their luck and do self-drive in Madagascar, the absolute majority of independent travelers visiting the country hire a car with a driver.

To Drive or Not to Drive

Our recent trip to the Southern Africa covered three countries, including Namibia, South Africa and Madagascar (see our complete trip itinerary here). While we were doing extensive self-driving in the former two countries, hiring a car without a driver in Madagascar just did not seem simple. Although we did find some occasional reports of “successful” self-drive trips on different travel forums, they did not cover our tentative route and described obstacles, which we were reluctant to go through on our trip to Madagascar.

Ferry Crossing over Tsiribihina River on the Way to Tsingy

Heading for Madagascar, one of the poorest countries in Africa, one has a plenty to worry about: personal safety, poor infrastructure and treacherous road conditions, overcrowded cities and villages, “ancient” car fleets and long distances between points of interest, just to name a few. In addition, our trip happened to coincide with the worst plague outbreak in Madagascar in the last 50 years. Although we cherished our privacy and independence, and had no prior experience with hiring a car WITH a driver, the compelling stories of fellow-travelers persuaded us to “go with the flow”.

Have your Itinerary Ready

Having done some research on the net, we had our tentative travel route penciled. The “grand plan” was to head out from Antananarivo (the capital) to Morondava on the west coast to spend a week visiting the unique deciduous forest of Kirindy and Tsingy Bemaraha National Park. Next we wanted to drive back to the central highlands and explore a couple of national parks and wildlife reserves along RN7 (without going all the way to Isalo). As a wrap-up, we would stay 5 days hiking in the primary and secondary rain forests of the Andasibe area east of Tana (Antananarivo).

Driving Across a Bridge in Andasibe

Choosing a Car Rental Agent

With this itinerary in hand, we contacted 7 travel agencies, which were offering car rentals in Tana, and asked them for quotes and advice regarding our route. Most tour operators (except those who were primarily selling tour packages) got back to us with reasonably consistent rates for car rental $65-75 per day for a four-wheel drive (4×4) car (SUV). These rates also covered the cost for an English-speaking driver (including his accommodation and meals). The fuel was extra (also some rental companies did bake it into their quotes).

Some tour operators tried to talk us out of visiting Tsingy Bemaraha on the West coast due to the impassable roads in the area during the wet season. We were traveling to Madagascar in November just before the rainy season, but we decided to keep our itinerary unchanged and to try our luck. To learn about the advantages and the drawbacks of traveling to Madagascar, Namibia and South Africa during the shoulder (off-peak) season read this post.

After a brief period of email exchanges, we zeroed down on GMT+3 (Great Madagascar Tours) agency, which was run by a local couple out of Antananarivo. Anja was very responsive to all our inquiries and requests and it made all the difference for us. We felt we could trust this business with our upcoming adventure and the 20% credit card deposit (which, by the way, was the simplest and the most reasonable arrangement relative to what the other car rental agencies were proposing).

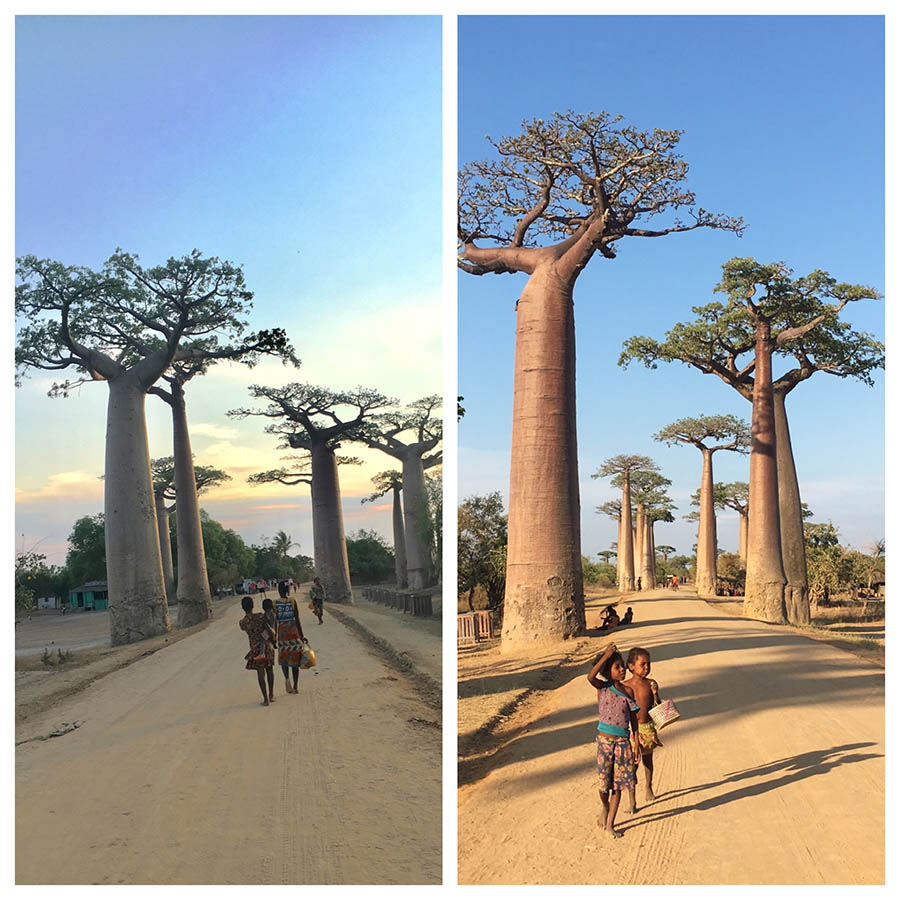

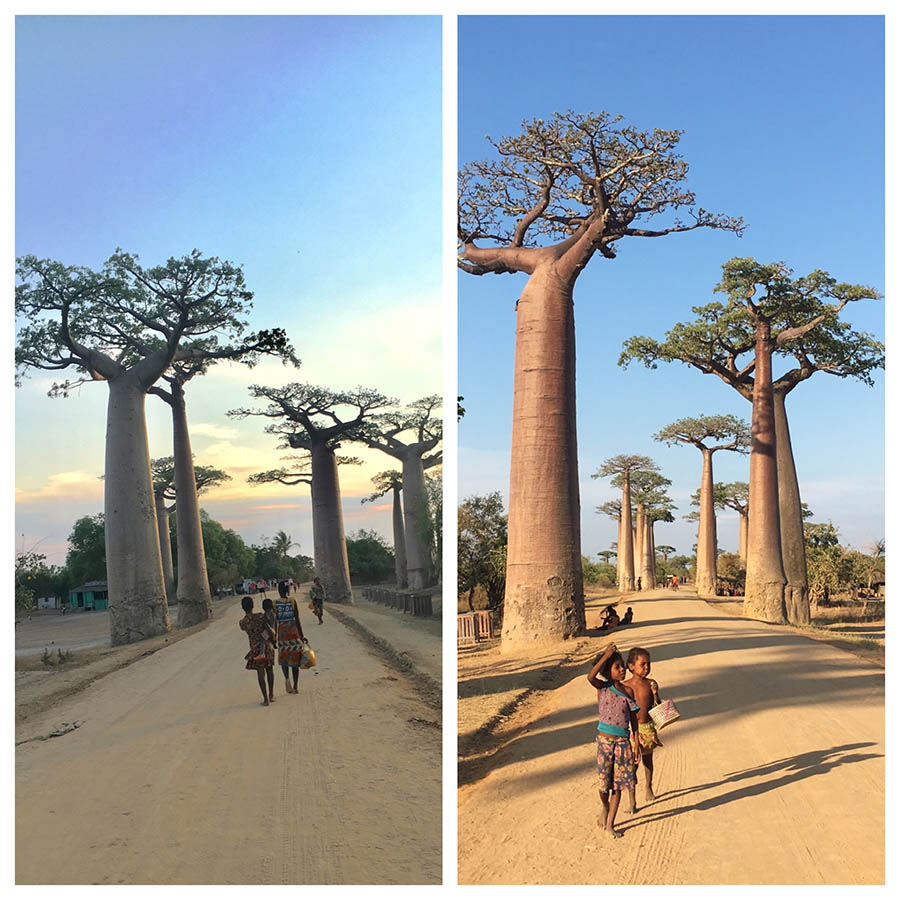

The Avenue of Baobabs in Morondava

Got More Than Expected – Literally

Given the situation with the plague, which was raging in the larger cities at that time, we decided to pay off the remaining car rental balance upon our arrival to Tana and leave for our 13-hour long non-stop drive west to Morondava as soon as possible. To spare us a trip through a chaotic street scene of the capital to the office, Anja sent Clio (his wife and a business partner) straight to our Airbnb with the car rental contract and last minute travel instructions (and to collect the remaining car rental payment in cash. Cash is KING in Madagascar).

The biggest surprise came when Cleo casually told us that instead of ONE English-speaking driver, we would get TWO guys for the “price of one”. Apparently, they did not have one person who could do both. While this might not be a common practice (although we did read about similar occurrences after the fact), we now believe to have benefited GREATLY from having a driver AND a guide on a trip with us.

Our Malagasy Driver (Tony) and the Guide (Martin)

Our Crew and the Rental Car

Bright and early next morning, Tony (our Malagasy-speaking driver) and Martin (a talkative English-speaking guide) cheerfully showed up at the gate of our Airbnb. Still processing this unexpected doubling in “staff”, we loaded our suitcases into an aged but sturdy-looking 4×4 dark-blue Hyundai and crawled onto the backseat. The longest leg of our journey across the island was ahead of us.

Here, I have to tell you that we had to change rental cars 3 times (including an unplanned break-down along RN34, see below) during our 17-day trip across the country. The stretch of the road along the west coast of Madagascar between Morondava and Tsingy Bemaraha National Park is considered to be a “vulnerable route”. And this is not ONLY due to the rugged terrain and treacherous driving conditions (which turn impassible during the rainy season).

Road between Morondava and Bekopaka (Tsingy Bemaraha)

Most tourists we met on the West coast of Madagascar were traveling in “convoys” of several cars. The “resort” in the Kirindy Private Reserve, where we stopped overnight for wildlife watching in a unique dry deciduous forest, had several local guards equipped with rifles at each corner for guest protection.

Not surprisingly, our car rental company had a prior arrangement with a local Sakalava driver (Lo-Lo), who replaced Tony (the driver who brought us to the West coast from Tana) in Morondava. Originally from the village of Belo, Lo-Lo was now living in a solid-looking house equipped with a large satellite dish along the main street of Morondova. He had the advantage of being intimately familiar with the route to Tsingy (which was nothing more than a rugged single track clay-colored dirt road) and the people living along the way. He had a sturdy high-clearance 4WD dusty Nissan with local registration plates, which would serve us well during the next 5 days in this “wilder” corner of Madagascar.

Road to Tsingy Bemaraha National Park

The Long Haul Across the Country on RN34

Traversing Madagascar from east to west and back were the most dreaded parts of our journey (9-12 hours each way). Although it ran along a largely paved RN34, many stretches were tortuous and rough, with regular deep potholes and washouts, often time without any shoulders.

Needless to say, there were no amenities along this route and whenever we stopped for 5 minutes breaks, we did not expect any privacy as there are people walking around ALL THE TIME. We were told to bring “white gold” on the trip with us. What is “white gold”, you would ask? Try toilet paper!! Most villages we passed along RN34 do not have any electricity and with many people on foot and livestock walking on the road, driving became especially hazardous in twilight, closer to the sunset.

2 hours into our 9-hour long drive on the way back from Morondava to Antsirabe, our car suddenly broke down in the middle of nowhere. It was late morning, but the temperature already was creeping into the uncomfortable high 30s Celsius. After spending one hour in the open sun (it was even hotter inside the stalled car) we started worrying about the prospects of getting stuck there. Aborting our trip and going back to Morondava seemed the best option at the time.

Fortunately, our Tony was able to contact our other driver Lo-Lo in Morondava, who came over flying in his car (our generous tips the night before probably helped A LOT there), and drove us all the way non-stop to Antsirabe. Once again, we counted our blessings and felt lucky to have rented a “car with a driver”. Our trip itinerary was salvaged!

The Car Breakdown on RN34

Navigating the Streets of Tana and Antsirabe

Although the roads within and around the larger cities, such as Antananarivo and Antsirabe were generally in a better condition, they were ALWAYS crowded. People were busy walking, selling and buying goods and just socializing.

Two-wheeled carts drawn by zebus or bullocks are still common sights on the roads of the highlands, especially around the cities and on market days. The rickshaw and the pousse-pousse, as it is called around there, are ubiquitous in the larger cities. And in Antsirabe, they seem to be a preferred mode of transportation. Throughout our trip in Madagascar, we experienced countless slowdowns to a crawl, traffic jams and hazardous driving situations in the densely populated area. All were masterly navigated by our expert driver(s) with a great deal of wisdom and patience.

Streets of Antananarivo in Madagascar

Driving RN7 through the Central Highlands

Traditionally, the best developed exchange economy and, therefore, the best road system in Madagascar has been located in the Merina and Betsileo sections of the central highlands, south of the capital. RN7 remains the most popular route for tourists due to its relatively good driving conditions. However, do not expect the quality even remotely close to what you would experience in Namibia and South Africa.

Sense of Privacy vs Sense of Place- When you Rent a Car with a Driver

As most independent travelers, who contemplate a car rental with a driver-guide, we had valid concerns about our privacy (or lack of thereof) during our trip. At the end of the day, we concluded that it was a small sacrifice we were glad to have made. Tony and Martin were so much more than a driver and a guide for us. They were our guardians, travel companions and entertainers, who did everything in their power to make our trip safe, comfortable and memorable.

In fact, next time we rent a car with a driver, we will definitely consider hiring a duo again as it has many advantages relative to a modest increase in cost (mostly in tips). By having both a driver and a guide, we could keep our belongings and the rental car under supervision at ALL TIMES and have a translator/interpreter accompanying us at all sites of interest, including banks or local village markets. We could rely on Martin making phone calls and hotel reservations for us “on the go”, while Tony (or Lo-Lo) was taking care of the driving.

When it comes to the time off-the-road, it was entirely up to us how much privacy we had. On several occasions, we did invite Tony and Martin out for drinks and dinner. Otherwise, we would agree on a time to meet on the following morning or afternoon and retire to our room for the rest of the day. There were simply no written rules in the contract on that sort of thing.

You’ll figure it out as you go. Keep it simple and enjoy the ride from the passenger seat of your rental car!

by mytravelcurator | May 12, 2019 | Africa, Namibia

The harsh and uninviting environment of the Namibian Atlantic Coast sparked our curiosity about its plants. On our springtime self-drive trip to the Skeleton Coast National Park, we got surprised by the variety of vegetation found there.

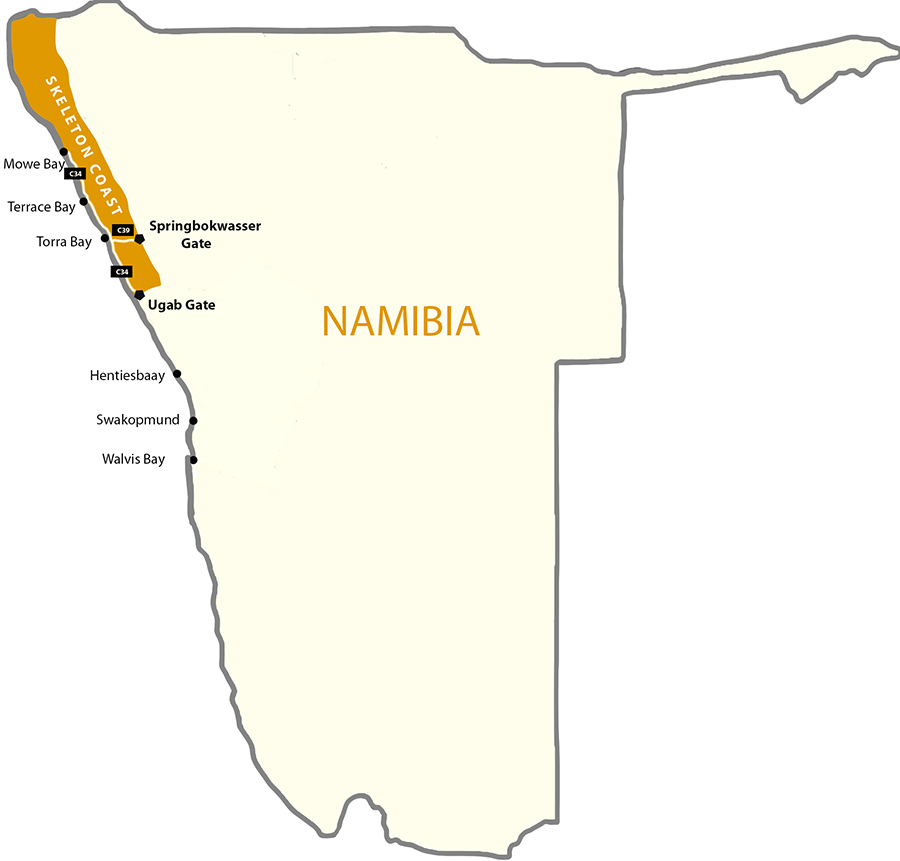

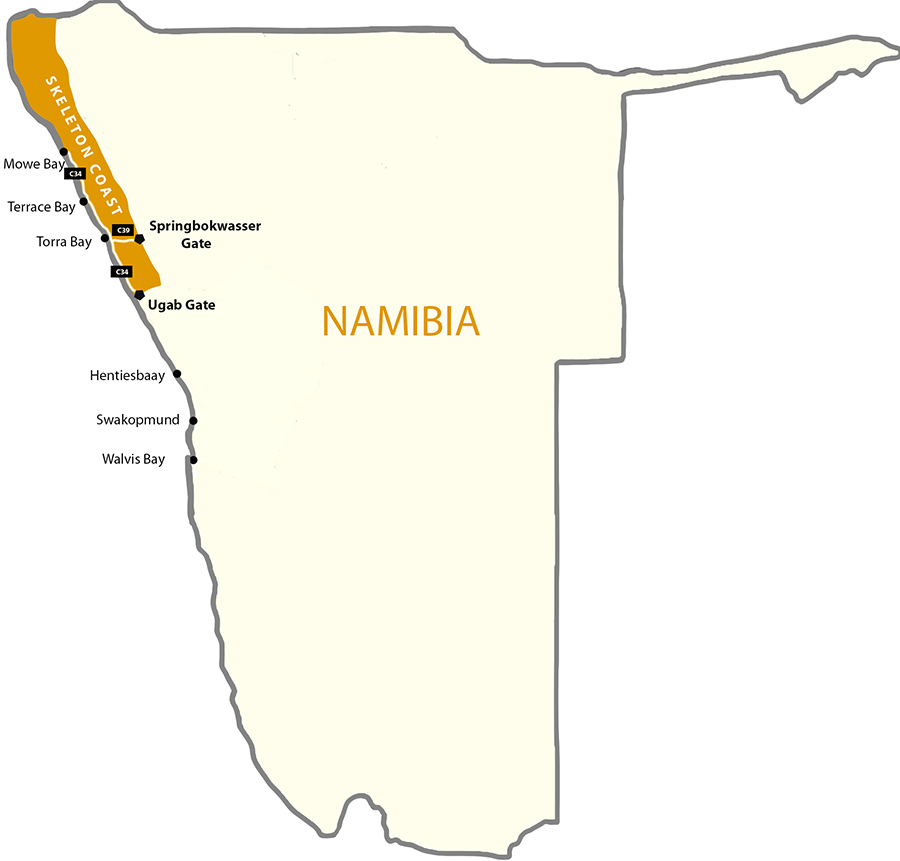

Skeleton Coast National Park Location

The Skeleton Coast of Namibia is dominated by several unique types of vegetation, each of which thrives in a specific habitat niche:

- Lichen fields, with over a hundred different species, some of which are rare and range-restricted to this area

- Salt– and brackish water-resistant dwarf shrubs and small trees abundant along the coast covered by sea salt and periodic salt-pans

- Seaweeds, with growth rates among the highest in the world, abundant along the coastline and include regional endemics of Southern Africa and the Benguela Marine Province

- Succulent and non-succulent desert-adopted plants of various sizes

- Grasses, tall shrubs and small trees common along the ephemeral riverbeds and underground streams

Salt-resistant Pencil bush on Terrace Bay

Skeleton Coast Climate and Water Sources

The Namib Desert is one of the driest places on Earth, with an average annual precipitation of about 2 cm along the Skeleton Coast. And some years, it does not rain at all. There are only two other coastal deserts in the world with a similar climate: the Atacama Desert on the Pacific Coast of Peru and Northern Chile, and the Sonoran Desert in Baja California. Unsurprisingly, there are significant similarities in vegetation patterns between those arid places and the Namibian Skeleton Coast. Many of their native plants and lichens also rely heavily on the coastal fog and dew as main water sources.

1. Fog vs. Rainfall

Despite the low to non-existent rainfall, the cold Benguela Current of the Atlantic Ocean by the Namibian shore brings over cool, moist fog on most days of the year (especially in the winter months). This dense atmospheric moisture is pushed further inland by the wind, where it disappears around noontime. This phenomenon keeps the average air humidity levels relatively high, within the Namibian fog belt.

The amount of fog moisture blown by the westerly wind through the coastal part of the Namib Desert is typically between 4-9 cm per year, which far exceeds the average rainfall precipitation (of 2 cm). Coastal fog is a source of not only moisture, but also nutrients. Moreover, it plays an important role in the formation of gypsum crust, which is a critical substrate for the “pioneering” lichen growth. See more information on gypsum-rich soil below.

2. Morning Dew

The annual average temperature on the Skeleton Coast is only 16 °C, with wild fluctuations between day and night. Because of these changes, the dew precipitation is significant in these parts of the world. Like fog, dew moisture is an important direct and indirect (through soil drip) water source for the wide variety of lichens and some succulent plants in this hyper-arid region.

3. Ground Water

In the Southern Namib Desert, almost no rivers reach the Atlantic Coast most of the year. In contrast, the ephemeral rivers cutting across the Skeleton Coast do form lavishly green linear oases throughout the otherwise desolate coastal desert landscapes. Some of these rivers and streams are completely hidden underground, but the water still sips through the surface bringing the desert landscape above the ground to life. River water is a lifeline for grasses, trees and the browsing wildlife.

Skeleton Coast Vegetation Pattern

Desert Plants Forming Sand Hummocks

As we traveled along the Skeleton Coast, we noticed that the vegetation varied wildly between the outer coastal areas and its interior. The outer zone of a few hundred meters was covered with low-growing succulent shrubs, such as the Namib endemic Dollar bush (Zygophyllum stapfii). Its Red book restricted-range relative Zygophyllum inflatum grows in the most northern section of the Skeleton Coast Park. Archaeological studies on the Skeleton Coast indicate that Dollar bush plants served as a major source of charcoal for the seasonal settlements of the local Namibian tribes in the past. Following the dry riverbeds, they were coming from the “hinterlands” of the Kaokoland to make use of the marine food resources available by the ocean.

Other salt-tolerant shrubs, such as Ganna or Saltbush (Salsola species) and Pencil bush (Arthraerua leubnitziae) also thrive along the sandy beaches of the Skeleton Coast Park. These plants trap sand particles forming sand hummocks, which provide habitat for local wildlife and form larger dunes over time.

The dominance of lichens throughout the Namib Desert is epitomized along the plains of the Skeleton Coast. Large sand dune-free areas, called “lichen fields”, stretch along route C34 on the Skeleton Coast road. The fog belt, with the moisture not available to most vascular plants, makes for perfect lichen living conditions. They grow on gravel surfaces and gypsum-crusted soil and become dormant (but do not die) when moisture is not available.

Plants of the Eastern Skeleton Coast

The gravel plains on the eastern edges of the Skeleton Coast are reminiscent of the Damaraland shrub lands, dominated by larger populations of Milk bush (Euphorbia damarana) and a few low-growing trees.

Lichen Fields of the Skeleton Coast

Skeleton Coast Landcape

The ability of lichens to survive on coastal fog and dew alone and to “cycle” between the dormant and active states make them perfectly adopted to the Skeleton Coast environment. Here, they are rich in species (although many are closely related) and the endemism level is impressive. Still, some species (e.g. Santessonia namibensis) living here are believed to have the smallest distribution ranges of all lichens in the world.

The first descriptions of Namibian lichens were published over one hundred years ago in “Die Pflanzenwelt Deutsch-Südwestafrikas”. Since then, over 100 lichen species living in the Namib Desert alone have been described (if you are looking for a field guide, check out “Lichens of the Namib Desert“ by Dr. Volkmar Wirth).

Given their microscopic size, the amount of “lichen biomass” along the Skeleton Coast is also impressive. For some “lichen fields”, it is reported being as high as 400 grams per square meter. The biological soil crusts they form in this hyper-arid land makes lichens the key flora of the Skeleton Coast.

Lichen fields are complex and fine-tuned ecological systems. Many environmental factors, such as moisture levels, soil acidity and salinity, availability of stable substrate (sand dunes vs gypsum crust vs gravel) and even its sloping angle determine lichen growth and distribution.

The prevailing winds on the Skeleton Coast shape the pattern of the vegetation cover. If you take a closer look at the lichen-covered rocks, you will notice that the colonies prefer living on the west-facing surfaces. This is because the Atlantic Ocean brings cool moist winds, whereas the winds from the East tend to blast the vegetation without mercy with deadly hot air and sand.

Off-road Car Tracks over Lichen Fields

A lichen fields is also a very fragile ecosystem. Once disturbed by tourist vehicles, it takes decades, if not a full century, for them to recover. Remember to stay on the road when driving through the Park!

Desert sand, which is constantly on the move, does not encourage lichen growth. In contrast, gravel stones littering the Skeleton Coast, and cemented gypsum crust serve as an excellent substrate for lichens.

Coastal fogs play a key role in the formation of the large areas of gypsum-rich soils on the Skeleton Coast. Here is how they are created, in a nutshell: H2S released by the ocean reacts with atmospheric oxygen and forms sulfate, which is then transported inland by the coastal fog, where (in the presence of calcium carbonate) it turns into gypsum (CaSO4·2H2O).

Vegetation of the Ephemeral Rivers

Grazing Oryx by Uniab River Oasis

As we continue driving north, several dry riverbeds cut across the desert landscape. Grasses and taller vegetation, such as wild tamarisk or “salt cedar” bushes (Tamarix usneoides), mopane trees (Colophospermum mopane) and makalani palms (Hyphaene petersiana), become more common here.

Makalani palms, native to Northern Namibia, are easily recognizable by their fan-shaped leaves. During our Skeleton Coast trip, we bought a few makalani palm nuts by the roadside to bring home as inexpensive souvenirs. These cute clumps of “plant ivory” were transformed into small pieces of handcrafted art by some local carvers. You can also find traditional ornamental bowls and baskets hand-woven with makalani palm leaves.

Ephemeral rivers and underground streams are important water sources for the local wildlife. These linear oases offer the best opportunity for game viewing in the Skeleton Coast National Park. You can often spot springbok and oryx antelopes grazing on lavish vegetation along the riverbeds. But be warned about the lions roaming the area. While staying in Terrace Bay for a night, we were told about these big cats frequenting the coast. You can track their movements around the Obab and other Skeleton Coast rivers on the “Desert Lion Conservation” website.

Skeleton Coast Marine Plants and Seaweeds

Seaweed Cast on Skeleton Coast

The outer part of the Skeleton Coast National Park is dominated by sandy beaches, with occasional rocky outcrops. The Benguela Current supplies large amounts of nutrients, feeding both marine animals and fields of seaweeds along the coast.

Although the diversity of the local sea flora is not as high as in the neighboring South Africa, it is considerably richer than in Angola and other countries of the West coast of the continent. A significant number the Namibian algae species are considered regional endemics to Southern Africa and the Benguela Marine Province (28.1% and 12.8% of flora, respectively). However, out of 196 described species, Acrosorium cincinnatum is the only endemic algae to Namibia. In addition to Swakopmund area, it has been found in Terrace Bay, Möwe Bay and at the Rocky Point in the Skeleton Coast National Park.

The seaweed variety along the Skeleton Coast features brown (Split-fan kelp or Laminaria pallida), green (Sea Lettuce or Ulva spp.) and red algae (Cape laver or Porphyra capensis, Red ribbons (Suhria vittata)). The epiphytic Yellow skin (Aeodes orbitosa or Pachymenia orbitosa) is more prevalent along the southern Namibia, where, in the sheltered waters, the size of its thallus (“leaf”) can reach 1-1.5 m in diameter. However, it has also been reported at Cape Frio and other locations of the Skeleton Coast.

Check out the “Marine benthic algae of Namibia” article for an overview of the Namibian seaweed variety and their geographic distribution, including those sampled in different locations along the Skeleton Coast.

The growth rate of algae in this part of the Atlantic Coast is one of the highest in the world. Some varieties (Laminaria pallida, Gracilaria verrucose) have been harvested in Namibia for commercial and domestic purposes.

Economical uses aside, seaweeds play an important ecological role along the Skeleton Coast. They serve as both food and shelter for marine and shore animals living in the inter-tidal zone. Swells and wind wash large amounts of seaweeds ashore. These plants decompose and provide nutrients to the soil-deprived sandy beaches, which dominate the Skeleton Coast National Park.

Rare and Endemic Plants of the Skeleton Coast

Nara Plant with Fruits

Nara plant (Nara melon or Acanthosicyos horridus) and Welwitschia mirabilis are unusual long-lived perennial plants and are both botanic curiosities of sorts. Despite their Namib Desert endemic status, neither is currently endangered (although Welwitschia does have a “protected” status in the country) because they are well adapted to their environment and are relatively common within their natural habitat.

Nara melon is a dune-growing Cucurbitacean plant, which forms dense bushes with branched light-green spiny stems and pale-yellow solitary flowers. The green fruits are also thorny and turn yellow or pale orange when ripe. They are not true desert plants and grow mostly in areas with underground water sources. Nara plants are far more ubiquitous in the Namib Sand Sea south of Swakopmund (the Sossusvlei and Sandwich Harbor are among the best viewing spots for this ecologically important desert species).

Welwitschia mirabilis is not as commonly seen along the Skeleton Coast as in other parts of Namibia. However, it can be found, if you know where to look. Check out where wild Welwitschia mirabilis grows post for 2 such locations near Ugab and Springbokwasser Gates of the Skeleton Coast Park.

Male plant of Welwitschia mirabilis

The majority of endemic and rare plant species of the coastal Namib Desert grow in the Sperrgebiet area (German for “forbidden territory”) further south. It is a part of a larger Succulent Karoo Region of the Southwestern Africa, one of the few recognized hot spots in the world with exceptional biodiversity.

Nonetheless, several Red Data Book plant species also live along the Skeleton Coast. The list of local endemics includes Aloe dewinteri Giess (Sesfontein-aalwyn), a smaller population of Cyphostemma juttae (a Cissus species) and a larger woody perennial plant Elephant’s Foot (Adenia pechuelii).

The upper part of the Skeleton Coast represents the northern limit of the natural habitat for peculiar dwarf succulents Lithops (Mesembryanthemums, also called “flowering stones” or vygies, locally). These regional endemics live almost exclusively (98% of all species) in the Succulent Karoo Region of Southwestern Africa. A few lithop species found outside of this region are believed to be dispersed and introduced there by shorebirds. Lithops ruschiorum, a Red Data Book endemic with a long-lasting yellow flower, lives in the Skeleton Coast National Park.

Lithops’ very short stem with a couple of thick fused leaves are sometimes barely visible in the sand and pebble ground cover. This peculiar appearance is an adaptation to the extremely dry environment. It allows for a reduction of surface area, while maximizing the leaf volume for water storage.

The most remote northern part of the Skeleton Coast is only accessible with fly-in tourist operators. In addition to the rare plants mentioned above, “cactus-like” stapeliads Hoodia currori, towering over the desert landscape, and Hoodia pedicellata (Trichocaulon pedicilfatum) can be spotted there.

This is also the natural habitat for the Namibian population of Adenium boehmianum. This plant is also called Bushman Poison, because the Heikom Bushmen apply its poisonous sap to their arrowheads for game hunting.

Unfortunately, poaching by succulent collectors and commercial dealers represents one of the biggest threats to these rare plants. You can learn more about Namibia’s threatened or endangered plants from this well illustrated on-line book “Red Data Book of Namibian Plants”

by mytravelcurator | May 5, 2019 | Africa, Namibia

The Welwitschia Plains near Swakopmund and the Coastal fog belt of Damaraland are the areas with most reported sightings of Welwitchia mirabilis since its discovery in Namibia. Below is an abbreviated map and detailed descriptions of 5 specific locations in Namibia, where you can find larger populations of Welwitschia plants in the wild. Most of them are based on our own sightings during the Unexpected Trip to Africa.

Discovery of Welwitchia mirabilis in Namibia

In September 1859, an Austrian botanist Friedrich Welwitsch made the first documented discovery of a new remarkable plant living on an elevated plateau near Cape Negro in Angola. He shared his findings with Dr. William Hooker, the director of the Royal Botanic Gardens, Kew at the time.

Shortly after, 500 miles south, Thomas Baines, an artist who was accompanying Dr. Livingstone on an expedition to the Zambezi River, drew several colored sketches of a big mysterious plant he found in the Namib Desert. Along with a few cones and leaves he collected, Baines sent his drawings of the “strange giant aloe” to William Hooker as well. This marked the official discovery of the “marvelous plant” Welwitschia mirabilis, in Namibia.

Today, you can see an oil painting created by Baines based on his original sketch at the Kew Library. Its caption reads “The Welwitschia mirabilis or Nyanka Kykamkop plant of Hykamkop, South West Africa. T. Baines. May 9 1861”.

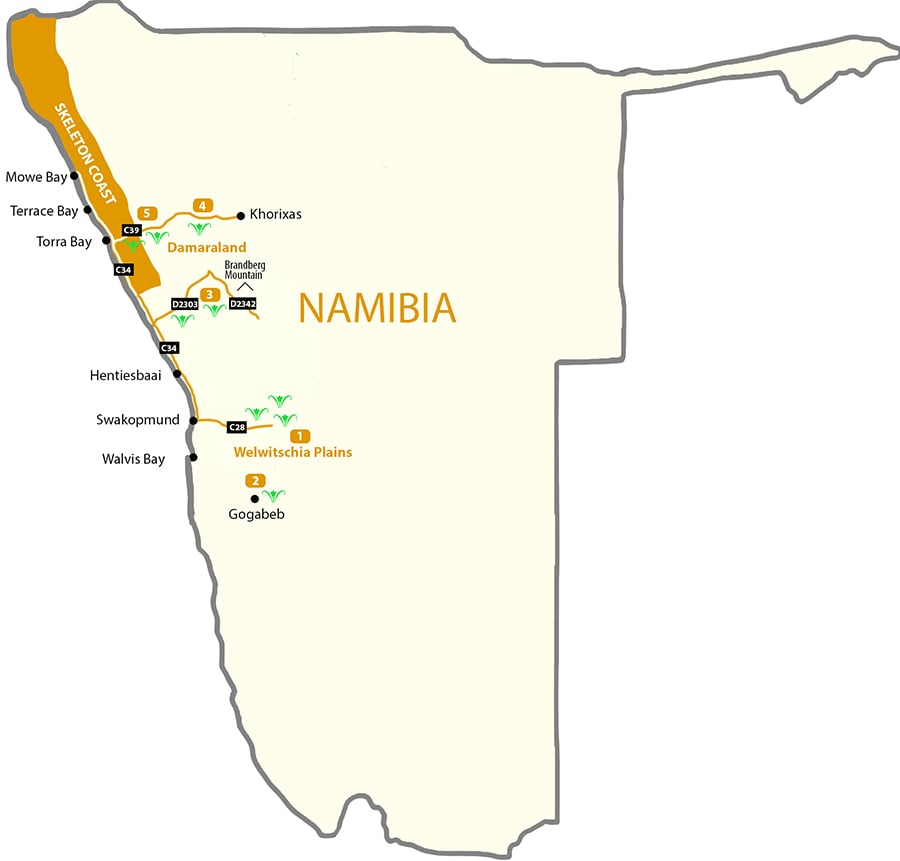

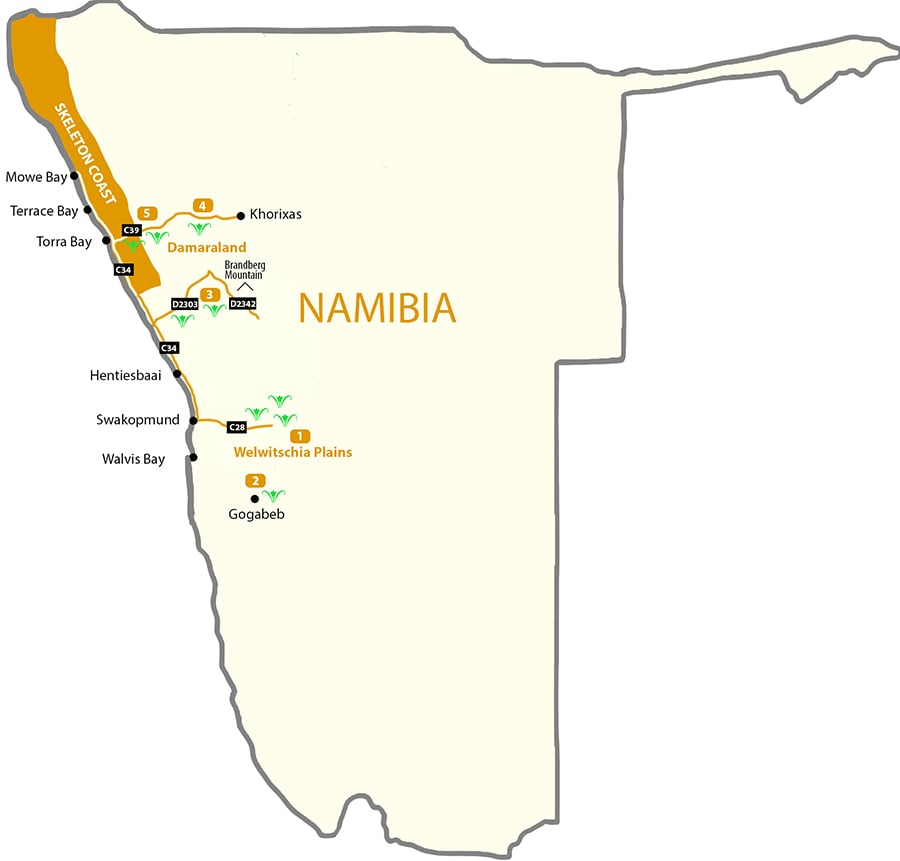

Map of the best viewing locations of Welwitschia mirabilis in Namibia

Welwitschia Mirabilis Natural Range and Distribution

Welwitschia mirabilis is a regional endemic of the Coastal Namib Desert. Its natural range extends over an area of 150,000 square km along the southwestern coast of Africa from the Kuiseb River (the Tropic of Capricorn) in central Namibia to the Bentiaba River in southern Angola. Its preferred habitat appears to be hyper-arid gravel plains or gypsum-rich soils.

The prominent Swedish explorer of Namibia Charles Andersson was writing in his notes “It is most common about the lower course of the River Swakop”. He also mentioned that it was growing in “the ground of hard quartzose character, and generally near little ruts worn in the plain by running water in the rainy season”. In 1862, the first living specimen of Welwitschia mirabilis was planted “with its native soil in a flour barrel” and shipped with a mail-steamer to join the botanical collection at Kew.

Below are five best locations in Namibia to see a variety of wild Welwitschia mirabilis plants growing within distinct, but equally natural habitats (numbered as on the map above).

1. Welwitschia Drive

The location the explorer Charles Andersson was referring in his early notes is believed to be Welwitschia Plains (also called Welwitschia Flats or Welwitschia Fläche). It is the most popular and widely advertised site in the Central Namib Desert for viewing Welwitschia plants. Situated between the Khan and Swakop rivers, it is a part of the Namib-Naukluft Park and has an easy access both from Swakopmund in the west and Windhoek in the east.

Typical landscape of the Welwitschia Plains

A permit, which can be obtained in Swakopmund, is required to access the Welwitschia Plains. With this permit, you will also receive a hand-drawn map of the Namib-Naukluft Park containing the small section dedicated to the Welwitschia Drive.

The tourist route from Swakopmund through Welwitschia Plains is called Welwitschia Drive. The round trip is 160 km and takes about 3-4 hours to tour with stops. It is an arid and barren place, but the area by the Swakop river provides some shade and is equipped with picnic tables and even campsites for overnight stays if desired.

You can download and bring along the official “The Welwitschia Plains – scenic drive” brochure, which includes a map and descriptions of all “attractions” along the route. Look for 13 labelled stone beacons. At the end of the Welwitchia Drive at the turning point, markers 11 & 12 will indicate the highlight of the trip, a larger group of very special Welwitschia (some female and male plants are marked with respective signs).

The Swakopmund location along the Welwitschia Drive boasts the oldest known plant colony, some of which are of remarkable size. The two largest Welwitschias (both female plants) in existence are growing here. These are also the oldest living Welwitschia plants, with an age of 1500 years (as estimated by carbon dating).

Chris Bornman details the enormous size on these peculiar plants in his article “Welwitschia mirabilis: paradox of the Namib Desert”: “The two tallest plants known, the Husab Welwitschia and the Pforte Welwitschia are 1.5 m and 1.9 m from the base to crown, respectively. The latter plant occupies an area 9.1 m in circumference and its stem, measured along the terminal groove, has a circumference of 5.7 m”.

Local mining activities resulted in excavation of some old Welwitschia plants in the area. This facilitated a study of their root system and the water sources. It showed that, contrary to a belief, the tap root was not all that long and did not measure more than 3 meters. Based on these and other observations, it was concluded that Welwitschia plants cannot rely on access to the ground water at 50-75 m depth for water supply.

2. Mine Hope and Welwitschia Wash on Kuiseb River

View of the Kuiseb River in dry season

The Tropic of Capricorn is the most southern frontier of Welwitschia mirabilis natural habitat range. This community of plants is little off the most popular tourist routes in Namibia, but it may be more accessible if you plan to visit the Gobabeb Research and Training Centre (GRTC). The Center, which is located about 120 km southeast of Swakopmund, has dedicated numerous studies of the Gobabeb population of Welwitschia mirabilis.

These plants are concentrated in tributaries of the Kuiseb River, 15 km (in the Welwitschia Wash) and 30 km (near the Hope Mine) from the Research Center. Apparently, you can make a reservation for your stay in the area by directly contacting the GRTC.

Welwitschia Plants of Damaraland

Unlike Welwitschia Plains near Swakopmund, the Welwitschia locations of Damaraland and the neighboring Skeleton Coast are not widely advertised. This may be because many of these places are more remote and some are notoriously difficult to get to. Below are the three areas in the Damaraland you might wish to explore in search of Welwitschia mirabilis.

Damaraland landscape

3. Welwitschia of Brandberg and Messum Crater

Amid vast desert plains, 250 km north the Welwitschia Drive, there is a granite massif with Namibia’s highest peak, the Brandberg Mountain (2,573m). It is at the foot of this mountain, Willie Giess (a botanist who was mapping Namibian plant communities back in the 1970s) found the largest Welwitschia plants ever recorded. Reportedly, he described a plant with a stem height of 1.8 m and another one with a stem diameter of 4 m near the Messum Crater (a large volcanic depression in the ground) west of Brandberg. However, some publications indicate that those giants since then burnt down by the lightening fire.

Unique Welwitschia plants with extra leaves (3-4, instead the usual 2) were also reported around here by Dieter von Willert in 1993. Two distinct types of extra-leafed Welwitschia were described in “Can Welwitschia mirabilis have more than only two Foliage leaves?”.

The first type had an additional pair of opposite leaves breaking through the top of the stem (more than a dozen of these were found among the 300 plants examined). The second variety had a single additional leaf. A group of nature enthusiasts on a follow-up “expedition” to this area in 2001 confirmed these findings. You can read their own account in “Torn to Ribbons in the Desert”.

A check list of 490 vascular plants living in the area (including Welwitschia mirabilis), can be found in “The flora of the Brandberg, Namibia”.

The Brandberg and Messum Crater area is best accessible via D2342 and D2303, off the Skeleton Coast road C34. Both D-roads are in a relatively good condition and are passable by a 2WD (although renting a car with higher clearance is advisable in these parts).

This amazing travel blog describes an adventurous 3-day journey of a biker along the same route (albeit in opposite direction) D2342 and D2303. There are also numerous photographs of the area, including those of the Brandberg Welwitscha population.

Ugab River Rhino Camp near the D2342-D2303 junction is the only place in the area where you can camp. However, you can visit the area as a day trip from Hentiesbaai (if you start early) or better yet from Cape Cross on C34.

Driving along the northern section of D2303 over the Ugab River is not recommended for independent tourists even by a 4WD. It is easy to understand after you hear the story about a well-travelled Dutch couple, Jan Snel and Mieke Schrijver, who got lost in that remote Burnt Mountain region of Damaraland and ran out of fuel in the late April 2003. They were stranded there without water for over two weeks. By the time they were found, Jan Snel died of dehydration and his wife was barely alive.

4. Welwitschia on the Fringes of the Skeleton Coast

Welwitschia grow along roadside of C39 just before you exit the Springbokwasser Gate of the Skeleton Coast National Park (30km from the Atlantic Coast). Curious about other unique plants along this route? Read the Skeleton Coast Plants post.

As you continue along beyond the Gate, a scenic view over the gravel plains opens up with numerous additional opportunities to get spectacular local welwitschia plants in the frame with the mountains of the Great Escarpment as a backdrop. These plants are “fed” by the water provided by the Koigab River, which “runs” faithfully along the road.

Male and female Welwitschia plants on gravel plains of Damaraland

If you keep driving for another 125 km on C39 (about 2 hours) from the Skeleton Coast National Park), you will be able to admire Welwitschia plans thriving in a different natural environment of the mopane savanna.

5. Welwitschia in Mopane Savanna near Khorixas

This unique population of Welwitschia plants grows along C39 west of Khorixas in Damaraland. The mean annual rainfall (150–200 mm) is significantly higher here than in the other Namibian Desert Welwitschia habitats described above. This is mopane savanna dominated by extensive grass cover, small shrubs and mopane trees.

If you are headed to see the Petrified Forest (45 km west of Khoraxis on C39), you won’t be able to miss the local Welwitschia growing there. They can be spotted rooted in sandstone right next to the 250 million years old fossilized pine trees, which are the major attraction of this site with the national monument status since 1950.

Mopane Savanna Landscape of Damaraland

by mytravelcurator | Jan 25, 2019 | Africa, Madagascar, Namibia, South Africa

Although Africa has been penciled on our “bucket list” of travel destinations for a long time, deciding which countries to visit and what time to go proved daunting. After some initial research and considerations, several destinations appeared attractive. Excellent tourism infrastructure made South Africa quite attractive for independent road travel. Namibia was calling for its spellbinding landscapes, whereas Madagascar has always been on my mind as the Promised Land for any wildlife enthusiast. An unexpected lay-off at work made it easier to embark on a longer trip and to visit several African countries on a single 40-day long trip.

South Africa – Namibia – Madagascar

40-day travel itinerary

South Africa (2 days)

(October 24-26)

Day 1: Cape Town, Woodstock (Old Biscuit Mill)

Day 2: Cape Town, City Bowl

Day 3: Departure for Walvis Bay, Namibia

Namibia (12 days)

(October 26 – November 6)

Day 3: Walvis Bay – Swakopmund (via Coastal Route)

Distance 40 km, travel time 1 hour

Day 4: Swakopmund – Sesriem (via C28)

Distance 344 km, travel time 5 hours

Day 5: Sossusvlei – Solitaire

Distance 142 km, travel time 2 hours

Day 6: Solitaire – Henties Bay (via Swakopmund)

Distance 332 km, travel time 4.5 hours

Day 7: Henties Bay – Terrace-Bay (via Cape Cross)

Distance 287 km, travel time 3.6 hours

Day 8: Terrace Bay – Kamanjab (via Damaraland)

Distance 300 km, travel time 4.5 hours

Day 9: Kamanjab – Etosha NP (via Galton Gate)

Distance 70 km, travel time 1 hour

Days 10-11: Etosha National Park

Day 12: Etosha NP-Spitzkoppe

Distance 417 km, travel time 4.5 hours

Day 13: Spitzkoppe-Sandwich Harbor (via Swakopmund)

Distance 200 km, travel time 2.5 hours

Day 14: Walvis Bay (Departure for Cape Town)

South Africa (3 days)

(November 6-9)

Day 15: Cape Town, Constantia (The Botanical Garden)

Day 16: Cape Town, Constantia (Vineyards & Wineries)

Day 17: Cape Town, Lion’s Head Sunset Hike

Madagascar (18 days)

(November 9-26th)

Day 18: Antananarivo – Arrival

Day 19: Antananarivo – Morondava (via Antsirabe)

Distance 700 km, travel time 12 hours

Day 20: Morondava – Kirindy

Distance 50 km, travel time 2 hours

Day 21: Kirindy Forest (Reserve)

Day 22: Kirindy – Bekopaka (Tsingy)

Distance 145 km, travel time 6 hours

Days 23-24: Tsingy de Bemaraha Nature Reserve

Day 25: Bekopaka – Morondava, via Belo Tsiribihina

Distance 206 km, travel time 8 hours

Day 26: Morondava – Antsirabe

Distance 483 km, travel time 8 hours

Day 27: Antsirabe – Ambalavao

Distance 297 km, travel time 6 hours

Day 28: Ambalavao – Anja Park (Reserve)

Distance 10 km, travel time 15 min

Day 29: Ambalavao – Ranomafana

Distance 117 km, travel time 2 hours 15 min

Day 30: Ranomafana National Park

Day 31: Ranomafana – Antsirabe

Distance 230 km, travel time 4.5 hours

Day 32: Antsirabe – Andasibe

Distance 312 km, travel time 5.5 hours

Day 33: Alamazoatra NP and Mitsinjo Forest

Day 34: Maromizaha Reserve

Day 35: Andasibe – Antananarivo

Distance 155 km, travel time 3.7 hours

Day 36: Antananarivo (Departure for Cape Town)

South Africa (4 days)

(November 26-30th)

Day 37: Cape Town, Oranjestad (Table Mountain National Park)

Day 38: Cape Town, Oranjestad (Boulders Penguin Colony, Cape of Good Hope)

Day 39: Cape Town, Oranjestad (Two Oceans Aquarium, Beaches of Cape Town)

Day 40: Cape Town-Heidelberg (via Road R44-R43)

Getting to South Africa from the United States

The total cost of flying between South Africa, Namibia and Madagascar was similar to the airfare between the U.S. and Cape Town. Collectively, our transportation expenses (excluding the car rentals) came to about $2,200 per person for the 10 flights we took during those 6 weeks. September appears as the ideal time of the year to visit these parts of the world, when the spring just starts setting in and the vast fields of wild flowers near Cape Town display bright splashes of color. However, for us, as independent travelers, it took 3 weeks was to make all the necessary arrangements for our multi-country travel itinerary.

As a result of lengthy trip planning phase, we did not leave Boston until the last week in October. To appreciate the advantages of traveling during the off-peak time, read Shoulder Season Traveling to Namibia and Madagascar. All reasonably priced trans-Atlantic flights from Boston to Cape Town at that time connected somewhere in the Middle East with painfully long layovers (9-11 hours) and would chip away at our precious vacation time. But hey, I have no job to rush back to … Needless to say, the only desire we had upon our arrival to the Cape Town Airport (CPT) was to hail a taxi to our downtown Airbnb apartment in Woodstock and hit the bed in this mysterious corner of the world…

by mytravelcurator | Jan 15, 2019 | Africa, Madagascar

A dramatic plague outbreak in Madagascar caught us unprepared just a few days before our recent trip to Africa. Apparently, it began as early as August 2017, and was spreading rapidly as the especially lethal pneumonic form. In contrast to the more common, bubonic type (which typically spreads by flees from rats and few other animal-hosts to people), pneumonic plague is transmitted from-person-to-person. By the time the news broke out, we had already made most of our Africa trip arrangements. However, as independent travelers, we had far more flexibility in shaping our upcoming vacation.

Hope for the Best, Prepare for the Worst

When facing potential health threats, like disease outbreaks, do not panic and cancel the trip right away. First, assess the situation objectively using the authoritative sources of information:

Through our independent research and travel clinic, we received loads of information about the disease and learned to recognize its symptoms. More importantly, we got enough antibiotics to last us through two full courses of treatment.

No Plague Vaccine, but Antibiotics are Highly Effective

Before leaving home, we visited our travel nurse to make sure we had all the necessary vaccinations and medicines for the trip. We shared out tentative itinerary with the map showing all routes and destinations.

Despite many years of basic and clinical research worldwide, there is still no safe and effective vaccine against this highly deadly infectious disease. However, several potential vaccine development approaches are being explored by scientists. Fortunately, the pathogen has remained relatively stable for hundreds of years, giving hope for successful plague prevention by vaccination. According to researches, the genetic makeup of the modern time bacteria does not seem too much different from the original plague bacteria.

Plague is highly curable with antibiotics, if detected and treated early. Moreover, drug-resistance has not been widely reported. Later during the outbreak, WHO reported that 33 isolates of Yersinia pestis had been cultured and tested by the Institut Pasteur Madagascar. All of them were sensitive to the antibiotics recommended by the National Plague Control Program. None of the 81 health care workers, who have been infected during the outbreaks died from the disease. This underscores the importance of safety measures, early disease diagnosis and access to antibiotics.

Keeping an Eye on Updates from Health Authorities

On the day of our departure to Africa, World Health Organization (WHO) reported that the death toll from the epidemic had reached 102 people. This number was surprisingly high and greatly exceeded those from the previous plague outbreaks in Madagascar. At the same time, 9 other African countries (including South Africa) were now at high alert due to a significant risk of a similar outbreak. The travel health advisories for Madagascar at CDC had changed: from “Watch Level 1, Practice Usual Precautions” to “Alert – Level 2, Practice Enhanced Precautions”.

Since Namibia was our first destination after Cape Town, we decided to keep monitoring the situation and the CDC status. Should it change to “Warning Level 3, Avoid Nonessential Travel”, we would have canceled our trip to Madagascar and visit several National Parks in South Africa instead.

History of Black Death in Madagascar

Plague was brought to Madagascar from India by boats back in 1898, as part of so called “third pandemics”. It reached the area of central highlands by 1920, where it has remained endemic ever since. Despite numerous outbreaks recorded in the major port cities, those locations do not appear to be persistent plague reservoirs in the country. Studies have shown that the costal environment hardly represents a suitable long-term ecological niche for the disease source. In many cases, the examined bacterial strains could still be traced to the highland areas. A similar route from the highlands to the coast was implicated into spreading of the latest plague outbreak of 2017.

The latest outbreak of 2017 was the pneumonic variety and was spreading throughout the major cities. Most previous occurrences were diagnozed as the bubonic type and were limited to small remote villages. The details of such a transformation of bubonic into pneumonic type of disease was described in detail: “The index case was a bubonic patient with a secondary lung infection, who contaminated a traditional healer and his family. Funeral ceremonies and attendance on patients contaminated other villagers. In total 18 cases were recorded, and eight died”.

“Turning of the bones” at Famadihana

As we were reading the news from the major media outlets, “dancing with the dead” was being “promoted” as THE REASON for the plague epidemics. They were referring to famadihana, traditional secondary burial rituals practiced by several highland tribes (mostly Imerina and Basileo). The custom, commonly known as “turning of the bones”, involves exhumation of deceased family members from the ancestral tombs. As their remains are being re-wrapped into fresh silk cloth and carried around by family members, the entire community celebrates with dancing, drinking and live music. Famadihana is based on the belief that the dead do not join the rest of their ancestors until their bodies reaches full decomposition with appropriate ceremonies and festivities.

The process could take up to several years and involves direct contact with corpses. There have been concerns that this burial practice could perpetuate the spread of plague and other diseases in Madagascar. However, firm scientific evidence to support such a connection between famadihana and the viscous cycle of the Black Death are profoundly lacking.

A large epidemiological study of plague cases in Madagascar reported that “the incidences were negligible during the period when the Famadihana tradition was presumably practiced”. Researchers believe that other environmental and anthropological factors are more likely to play a larger role in spreading the plague. The pathogen’s natural host is the black rat (Rattus rattus), which also infested the island more than a century ago. During the cool and dry season (July-December), the population of rats drops. The fleas start feeding of people, thereby, transmitting the disease and leading to regular outbreaks.

Monitoring the Outbreak Status

Upon our return from Namibia, we checked the updates issued by WHO. The outbreak appeared to had peaked in October and the number of new cases were decreasing. More than half of all cases had been reported in the capital of Antananarivo and the main port of Toamasina, the largest cities in Madagascar. The CDC had not raised their alert level and the flights from South Africa for Madagascar were leaving as scheduled. At that point, we decided to pursue our original travel plans. However, we did modify our itinerary to avoid prolonged stays in the larger cities and visits to crowded places. Quite predictably, only 18 seats (out of over a hundred) were taken on the plane bringing us from Johannesburg to Antananarivo.

Preventing the Future Epidemics

Most of our time in the country, was spent in transit and visiting national parks. We did explore some small villages, local markets and artisanal workshops in the highlands, but kept those activities to a minimum. Better safe than sorry. One early evening, we witnessed a heated discussion on the veranda of our small hotel in Ambalavao province. It was a multidisciplinary team of European health care professionals from Doctors without Borders in the middle of a brainstorming session. These were doctors, nurses and social workers tasked with educating the local population and medical personnel about plague prevention, symptom recognition and treatment.

They sounded undeterred and optimistic about finding a long-term solution to plague outbreaks in the country. As their colleagues worldwide, they passionately advocated for increased research, prevention and treatment efforts by the Malagasy authorities and the international community.

by mytravelcurator | Jan 10, 2019 | Africa, Cape Town, South Africa

Prior to our recent trip to Africa, Woodstock was not on the initial list of places to visit in Cape Town. However, the promise of the “panoramic views of the city” by a local Airbnb owner caught our attention. Following an 30-hour trip from Boston to South Africa and a short taxi ride from the airport, we finally reached our destination. Wrestling with the jet lag and fatigue, we were slowly settling down. Urged by the nagging hunger, we decided to venture out and explore the neighborhood. Within an hour, we were on our way to the Old Biscuit Mill, just a mile away.

Walking in Woodstock

This was an early evening and the end of a work day. The factory workers started pouring out through the gates of the local factories, quickly filling up the streets and the bus stop areas. Unlike other more segregated neighborhoods we stayed at during our time in Cape Town, Woodstock was a multiracial community. As we learned, it also represented a poster child of the ongoing urban gentrification in the city. As a true melting pot, is had a special edgy vibe and, admittedly, some rough element.

When we inquired with two local residents whether it was safe to walk along Albert road, the answer was “sometimes it is…”. While buying a bottle of water at a small local shop, its owner provided us with an unsolicited advice at the checkout: “You must be new around here, as you keep too much cash visible in your wallet”.

The Price of Revival

In the recent years, Woodstock has been undergoing a makeover from a grim industrial patch into a vibrant business hub and an attractive residential area. However, this recent transformation has come at a cost. As the property values kept rising, less fortunate long-time residents of Woodstock were experiencing evictions and displacement. Many ended up living in the rusty metal shucks on the nearby “human damping” grounds, like Blikkiesdorp (“Tin Box Town” in Afrikaans). While widely criticized for not being more inclusionary, the undaunted entrepreneurs have remained busy at work. Almost on every corner, you will see examples of new and beautifully restored residential and commercial buildings.

The Old Biscuit Mill

When we finally got to the Mill, we discovered several artsy shops, creative studios and eateries on the block. There was also a secure larger parking area nearby. If you, just like us, has failed to make a several-months-in-advance reservation to The Test Kitchen (which is ranked among the best restaurants in the World with an impressive list of domestic and international awards), try a juicy lamb burger (The Karoo Grazer) at Redemption Burgers instead. Don’t forget to complement it with a pint of refreshing local craft beer or cider. They are simply delicious! If you are in the area on Saturday, make sure to visit the Neighbourgoods Market. It’s best experienced early in the morning, before the crowds.

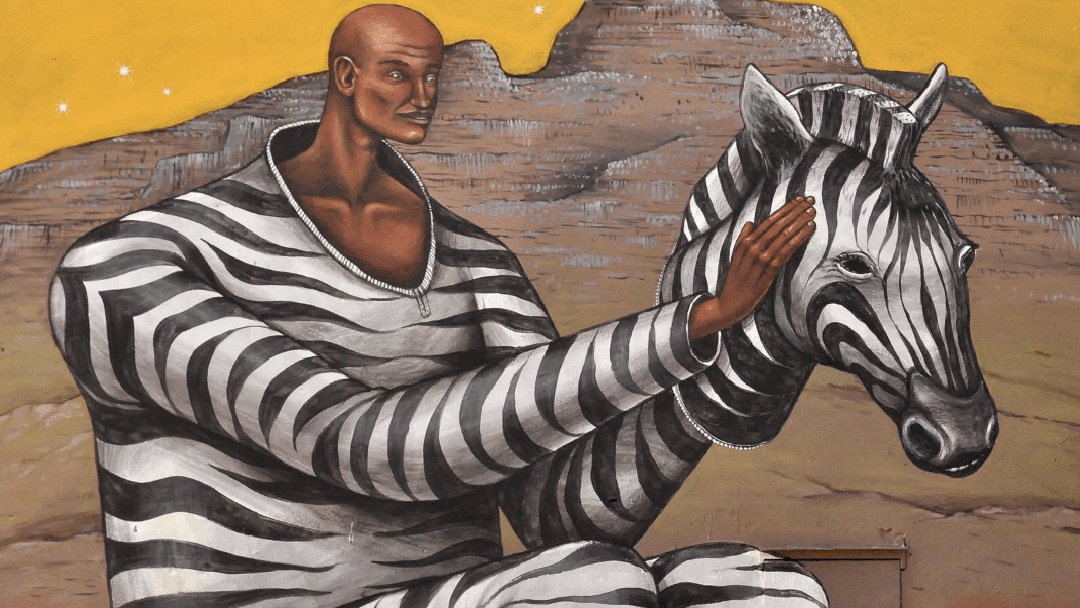

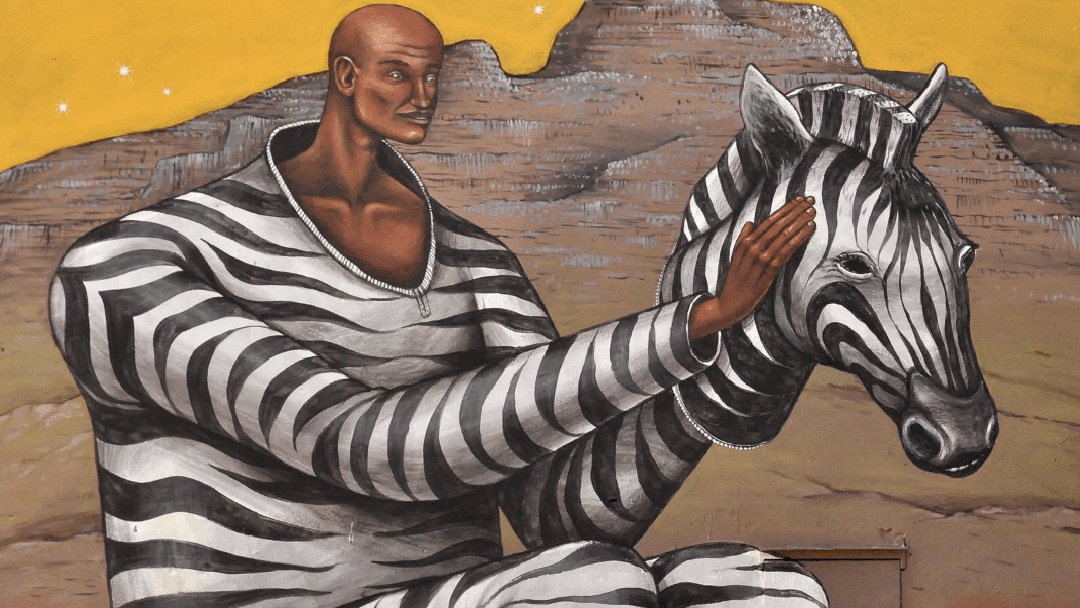

Street Art in Woodstock

Visiting Woodstock during the day, one can then embark on an “street art safari” for entertainment. This is a recent urban art project featuring a variety of masterpieces, including the creative “Black or White?” mural (see the blog post image) by Aleksei Bordusov aka Aec Interesni Kazki. For a detailed “street safari” itinerary and other things to do in Woodstock, check out the “Secret Cape Town (Local guides by local people)” book by Justin Fox and Alison Westwood. It is also loaded with other recommendations for “off-the-beaten-track” places to explore while staying in Cape Town.

Safety Rules and Water Shortage

After our “night out” (the Old Biscuit Mill closed at 5pm), we prudently flagged down a taxi to get back to our place. Using public transport or walking the backstreets of Woodstock (especially after dark) was not widely advised by the local residents and the visitors alike.

Aware of the fact that Cape Town was going through its worst drought in decades, we kept our showers very brief. We also collected the water for re-use, as requested by our host in her “instructions for the guests”. We learned later on that this was just the beginning of the worst drought in Cape Town in decades. Struggling with the stubborn jet lag, we finally fell asleep. The calls to the morning prayer were coming from a nearby mosque, breaking the silence of the night.