by mytravelcurator | May 19, 2019 | Central America, Costa Rica

The King Louis Waterfall, just off the Matapalo Beach Road is a hidden gem on Osa Peninsula in Costa Rica. One does not have to be exceptionally fit or daring to visit it, but some planning is required to make this trip a success. Read on to learn about the place, when to go and how to find it.

King Louis Waterfall Info

King Louis Waterfall in Matapalo

Time Required:

Depending on whether you are staying in Matapalo or coming from Puerto Jimenez, plan to spend 4 to 5.5 hours total (perfect as a half-a-day trip):

- 3 hours (with 30 min climb each way) for the waterfall visit itself

- 1 hour (30 min each way) to walk along Matapalo Beach Road

- 1.5 hour (40-45 min each way) to get to Matapalo Beach Road (if you start your trip from Puerto Jimenez)

- Best Time to Visit: starting early in the morning (around 7 am) is absolutely the best time to enjoy the solitude (before “the crowd” arrives), to have a better opportunity for wildlife watching, and to enjoy cooler temperatures

What to Bring:

- Water and food (there are NO shops or restaurants in the area)

- Hiking boots or comfortable non-slip sneakers (avoid flip-flops, sandals etc., we have seen tourists turning around half-way into the climb, because they did not have proper shoes to complete the hike all the way to the waterfall)

- Binoculars and/or camera with a long-lens for wildlife viewing

- Beach towels and swimwear for refreshing dips in waterfall pool, cascades and at nearby beaches.

How to get there:

- Drive or take a bus/taxi to the Matapalo Beach Road if you start in Puerto Jimenez

- Our advice: Do not drive on the Matapalo Beach Road! and take a pleasant 30-min walk (about 1 mile) instead

- At the very end of this dirt road by the beach, look for a short offshoot in the right and the “Catarata” sign (Spanish for “Waterfall”) on a tree trunk (see the blog picture above and follow the details further below). This is the head of the King Louis Waterfall trail

- Follow a poorly marked trail along the stream (we counted ONLY a handful of those “red-and-white” tags like the one attached next the “Catarata” sign) as you climb up all the way to the waterfall

Matapalo Beach Road to the Waterfall Trail

As I mentioned above, driving along the Matapalo Beach Road is not recommended, unless you have an ATV or a car with a VERY good clearance (simply having a standard 4×4 car is not enough). The road is riddled with deep potholes and littered with large rocks. Just be sure not to block any traffic (the local property owners, staff and some vacationers do take their pick-up trucks, dirt bikes and ATVs through there).

You can park your car by Playa Pan Dolce (the first beach off Matapalo Beach Rd.) as you leave the main road leading to the Carate Gate of the Corcovado National Park. If you do decide to drive on, but change your mind, you may also park your car by the Playa Carbonera down the road and walk the remaining distance. This is something we did after we realized the road was in a very poor condition.

If you set out in the morning, your walk will be mostly in the shade (until the very last few hundred feet). During this early hour, you might have your first wildlife-watching opportunities of the day. Spotting interesting birds is easy around here. On our walk along the Matapalo Beach road, we passed several small guided bird watching parties scouting the dense vegetation with their Swarovski scopes and binoculars.

Along the way, you will see occasional small lodges and private vacation homes.

Finding and Climbing the King Louis Waterfall Trail

King Louis Waterfall Trail Head Sign

Towards the end of the road, you will also be able to see the beach through the vegetation on your left. As the road starts curving sharply to the left, there is a smaller less-traveled “offshoot” on your right. Follow it for another hundred feet till you see a big tree with “Catarata” sign and an arrow attached to its trunk. If the road ended and you are facing the beach, you’ve walked a hundred feet too far.

Just as it is tricky to find the trail start, it is hard to know for sure where exactly the trail goes after you start your climb. If you begin early, you likely won’t see anyone there to show you the way. However, the rocky passage is rather narrow, and it is hard to get lost. One short section of the trail is equipped with a guide rope.

We did not meet a sole on the way up (while seeing at least 10 people on the way back). As you continue pushing forward, there will be a couple of smaller cascades on route to take a dip and cool down.

Swimming and Waterfall Rappelling

After a half-an-hour climb, we’ve finally reached the waterfall! It was the tallest waterfall we’ve seen in Southern Costa Rica so far. Surrounded by the massive mossy rocks and towering rainforest trees, we spent a couple of hours swimming, reading and enjoying the solitude.

If you are looking for even more adventure and a jolt of adrenaline, you may wish to look into other options to visit the King Louis Waterfall. Some local lodges in Matapalo and tour operators in Puerto Jimenez will offer you both tree-climbing and waterfall rappelling tours in the area.Check out this blog post for a vivid narrative about such a adventure.

Refreshing Dip into Waterfall Pool

Viewing Spider Monkeys by the Waterfall

Wildlife sightings is something one can hope for but can never be guaranteed. However, the remote location and proximity to the Corcovado National Park makes King Louis Waterfall area a perfect place for such rare encounters.

After we settled and quieted down by the “pool”, I suddenly spotted a couple of larger monkeys moving briskly through the canopy. A moment later, two more monkeys joined them in the same tree. Since we did bring our binoculars on this hike, I was happy to have my long camera lens as a substitute.

This was our first sighting of a Spider monkeys in Costa Rica (the second one was a rather brief encounter a few days later along the private Osa trail of the Lapa Rios Ecolodge). It was 2 female monkeys, each having a tiny white-faced baby clinging to their mothers.

There was also a younger adult, who was bouncing back and forth between “socializing” with the females (one of which was probably his mother) and carefully exploring the surroundings nearby on his own. The entire time, they seemed to ignore our presence and it was hard to take our eyes off this entertaining family scene.

The patch of the rainforest around the waterfall is a prime natural habitat for Spider monkey, who are frugivores and need to roam large areas with tall primary-growth trees and plenty of fruits to survive. Since this type of primary rainforest remains scarce, Spider monkey is currently one of the most endangered primate species in Costa Rica and Central America.

Spider Monkey Family by the Waterfall

We Will Be Back

All in all, this hike to the King Louis Waterfall was definitely one of the highlights on our trip to the Osa Peninsula. We would highly recommend it to nature lovers and adventure-seekers alike. While many Costa Rican waterfalls are slowly turning into crowded “tourist traps”, this one remains a pristine and quiet place. This also one of very few hiking opportunities in Matapalo with public access. Most hiking trails in this area are privately owned and their use would require special arrangements.

Enjoy Pristine Matapalo Beaches and More Wildlife

But wait, there is more. You might consider extending your Waterfall trip by visiting one or more of the nearby beaches on the way back. And not necessarily only for swimming and sun worshiping. You can follow the beach along the Matapalo Beach Road all the way back to the main road. Or you can combine walking in the shade with spending sometime on each of the gorgeous beaches.

On our way from the waterfall, while exploring the Carbonera Beach (halfway between the waterfall trail and the main road), we ran into a troupe of well over a dozen of White-faced Capuchin monkeys. We spent the next 45 minutes watching these highly social and dexterous foragers doing “their normal thing” in the bush.

White-faced Capuchins on Matapalo Beach

In truth, we were not sure, who was watching who during that thrilling encounter. It started a little “stand-off-ish”, as the alpha male approached us rather closely, while flashing his teeth. However, after a few tense minutes of “measuring up to his competition”, he plumped down on a nearby branch and assumed a rather relaxed napping posture (watch a 1 min video of this guy). Seemingly relieved, his entire following proceeded by going about their own business as well.

Despite all that grooming, eating and quarreling, they clearly kept an eye on us and what “we were up to” at every given moment. As I learned later from several reads on the subject, Capuchin Monkeys are often attracted by any “activities” on their territory. They are notorious for frequently “stalking” people and many other animal species. To learn more about the White-faced Capuchins and the other three species of monkeys we met during our week-long stay in Matapalo, read my post “Find all Costa Rican Monkey Species in One Place”

by mytravelcurator | May 12, 2019 | Africa, Namibia

The harsh and uninviting environment of the Namibian Atlantic Coast sparked our curiosity about its plants. On our springtime self-drive trip to the Skeleton Coast National Park, we got surprised by the variety of vegetation found there.

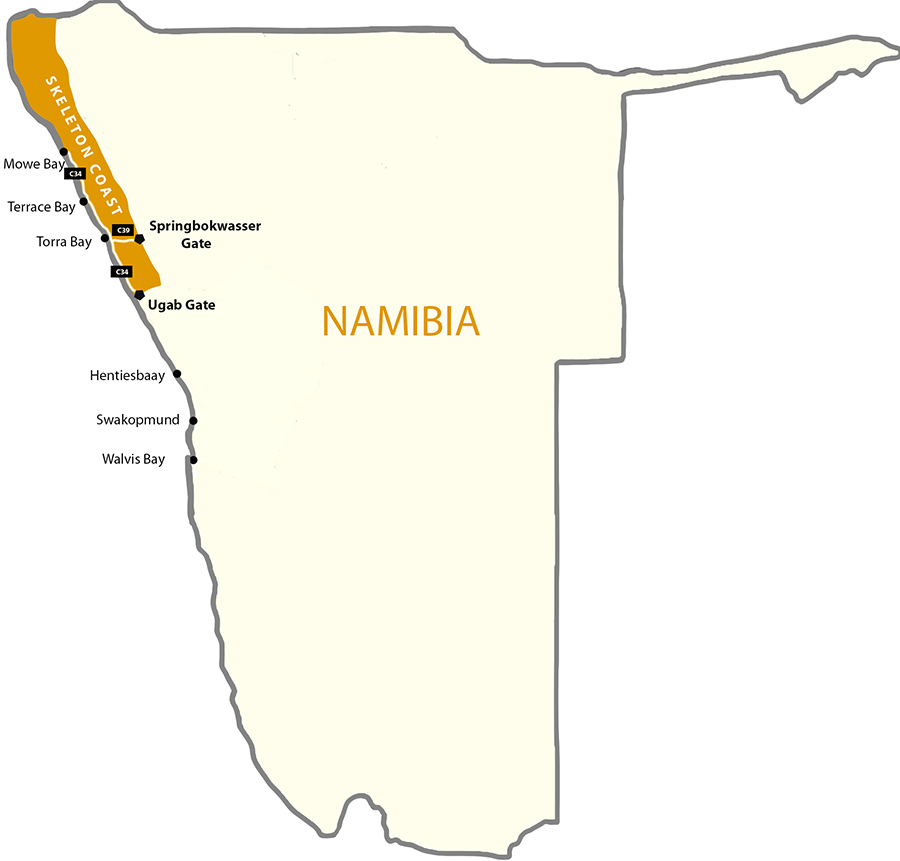

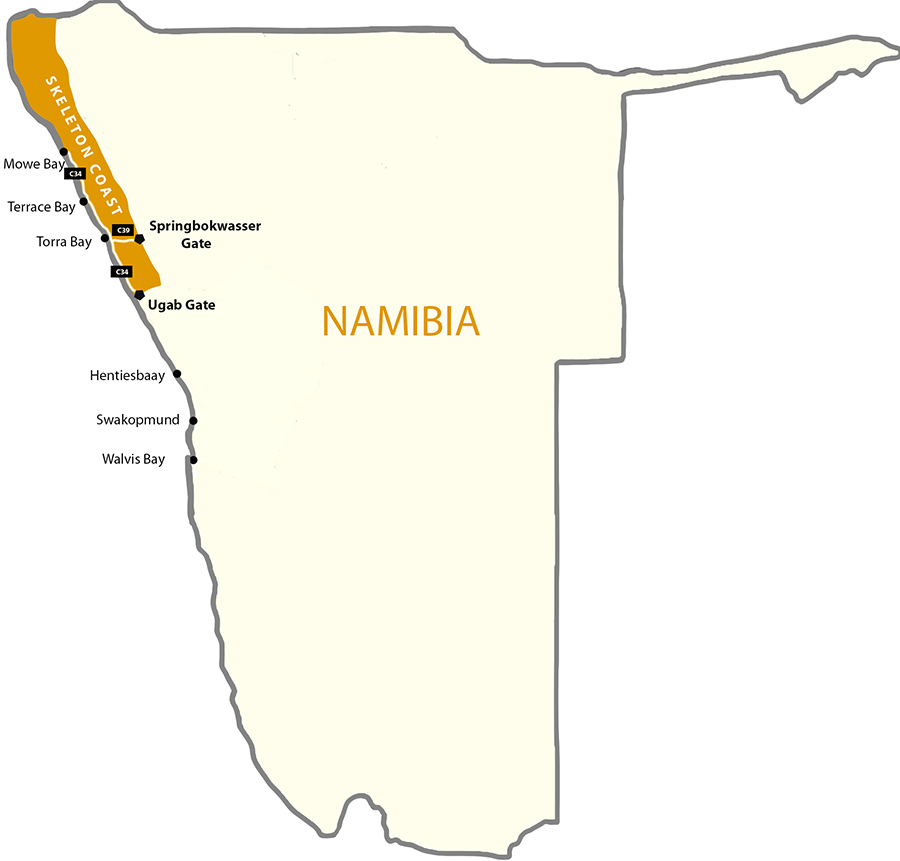

Skeleton Coast National Park Location

The Skeleton Coast of Namibia is dominated by several unique types of vegetation, each of which thrives in a specific habitat niche:

- Lichen fields, with over a hundred different species, some of which are rare and range-restricted to this area

- Salt– and brackish water-resistant dwarf shrubs and small trees abundant along the coast covered by sea salt and periodic salt-pans

- Seaweeds, with growth rates among the highest in the world, abundant along the coastline and include regional endemics of Southern Africa and the Benguela Marine Province

- Succulent and non-succulent desert-adopted plants of various sizes

- Grasses, tall shrubs and small trees common along the ephemeral riverbeds and underground streams

Salt-resistant Pencil bush on Terrace Bay

Skeleton Coast Climate and Water Sources

The Namib Desert is one of the driest places on Earth, with an average annual precipitation of about 2 cm along the Skeleton Coast. And some years, it does not rain at all. There are only two other coastal deserts in the world with a similar climate: the Atacama Desert on the Pacific Coast of Peru and Northern Chile, and the Sonoran Desert in Baja California. Unsurprisingly, there are significant similarities in vegetation patterns between those arid places and the Namibian Skeleton Coast. Many of their native plants and lichens also rely heavily on the coastal fog and dew as main water sources.

1. Fog vs. Rainfall

Despite the low to non-existent rainfall, the cold Benguela Current of the Atlantic Ocean by the Namibian shore brings over cool, moist fog on most days of the year (especially in the winter months). This dense atmospheric moisture is pushed further inland by the wind, where it disappears around noontime. This phenomenon keeps the average air humidity levels relatively high, within the Namibian fog belt.

The amount of fog moisture blown by the westerly wind through the coastal part of the Namib Desert is typically between 4-9 cm per year, which far exceeds the average rainfall precipitation (of 2 cm). Coastal fog is a source of not only moisture, but also nutrients. Moreover, it plays an important role in the formation of gypsum crust, which is a critical substrate for the “pioneering” lichen growth. See more information on gypsum-rich soil below.

2. Morning Dew

The annual average temperature on the Skeleton Coast is only 16 °C, with wild fluctuations between day and night. Because of these changes, the dew precipitation is significant in these parts of the world. Like fog, dew moisture is an important direct and indirect (through soil drip) water source for the wide variety of lichens and some succulent plants in this hyper-arid region.

3. Ground Water

In the Southern Namib Desert, almost no rivers reach the Atlantic Coast most of the year. In contrast, the ephemeral rivers cutting across the Skeleton Coast do form lavishly green linear oases throughout the otherwise desolate coastal desert landscapes. Some of these rivers and streams are completely hidden underground, but the water still sips through the surface bringing the desert landscape above the ground to life. River water is a lifeline for grasses, trees and the browsing wildlife.

Skeleton Coast Vegetation Pattern

Desert Plants Forming Sand Hummocks

As we traveled along the Skeleton Coast, we noticed that the vegetation varied wildly between the outer coastal areas and its interior. The outer zone of a few hundred meters was covered with low-growing succulent shrubs, such as the Namib endemic Dollar bush (Zygophyllum stapfii). Its Red book restricted-range relative Zygophyllum inflatum grows in the most northern section of the Skeleton Coast Park. Archaeological studies on the Skeleton Coast indicate that Dollar bush plants served as a major source of charcoal for the seasonal settlements of the local Namibian tribes in the past. Following the dry riverbeds, they were coming from the “hinterlands” of the Kaokoland to make use of the marine food resources available by the ocean.

Other salt-tolerant shrubs, such as Ganna or Saltbush (Salsola species) and Pencil bush (Arthraerua leubnitziae) also thrive along the sandy beaches of the Skeleton Coast Park. These plants trap sand particles forming sand hummocks, which provide habitat for local wildlife and form larger dunes over time.

The dominance of lichens throughout the Namib Desert is epitomized along the plains of the Skeleton Coast. Large sand dune-free areas, called “lichen fields”, stretch along route C34 on the Skeleton Coast road. The fog belt, with the moisture not available to most vascular plants, makes for perfect lichen living conditions. They grow on gravel surfaces and gypsum-crusted soil and become dormant (but do not die) when moisture is not available.

Plants of the Eastern Skeleton Coast

The gravel plains on the eastern edges of the Skeleton Coast are reminiscent of the Damaraland shrub lands, dominated by larger populations of Milk bush (Euphorbia damarana) and a few low-growing trees.

Lichen Fields of the Skeleton Coast

Skeleton Coast Landcape

The ability of lichens to survive on coastal fog and dew alone and to “cycle” between the dormant and active states make them perfectly adopted to the Skeleton Coast environment. Here, they are rich in species (although many are closely related) and the endemism level is impressive. Still, some species (e.g. Santessonia namibensis) living here are believed to have the smallest distribution ranges of all lichens in the world.

The first descriptions of Namibian lichens were published over one hundred years ago in “Die Pflanzenwelt Deutsch-Südwestafrikas”. Since then, over 100 lichen species living in the Namib Desert alone have been described (if you are looking for a field guide, check out “Lichens of the Namib Desert“ by Dr. Volkmar Wirth).

Given their microscopic size, the amount of “lichen biomass” along the Skeleton Coast is also impressive. For some “lichen fields”, it is reported being as high as 400 grams per square meter. The biological soil crusts they form in this hyper-arid land makes lichens the key flora of the Skeleton Coast.

Lichen fields are complex and fine-tuned ecological systems. Many environmental factors, such as moisture levels, soil acidity and salinity, availability of stable substrate (sand dunes vs gypsum crust vs gravel) and even its sloping angle determine lichen growth and distribution.

The prevailing winds on the Skeleton Coast shape the pattern of the vegetation cover. If you take a closer look at the lichen-covered rocks, you will notice that the colonies prefer living on the west-facing surfaces. This is because the Atlantic Ocean brings cool moist winds, whereas the winds from the East tend to blast the vegetation without mercy with deadly hot air and sand.

Off-road Car Tracks over Lichen Fields

A lichen fields is also a very fragile ecosystem. Once disturbed by tourist vehicles, it takes decades, if not a full century, for them to recover. Remember to stay on the road when driving through the Park!

Desert sand, which is constantly on the move, does not encourage lichen growth. In contrast, gravel stones littering the Skeleton Coast, and cemented gypsum crust serve as an excellent substrate for lichens.

Coastal fogs play a key role in the formation of the large areas of gypsum-rich soils on the Skeleton Coast. Here is how they are created, in a nutshell: H2S released by the ocean reacts with atmospheric oxygen and forms sulfate, which is then transported inland by the coastal fog, where (in the presence of calcium carbonate) it turns into gypsum (CaSO4·2H2O).

Vegetation of the Ephemeral Rivers

Grazing Oryx by Uniab River Oasis

As we continue driving north, several dry riverbeds cut across the desert landscape. Grasses and taller vegetation, such as wild tamarisk or “salt cedar” bushes (Tamarix usneoides), mopane trees (Colophospermum mopane) and makalani palms (Hyphaene petersiana), become more common here.

Makalani palms, native to Northern Namibia, are easily recognizable by their fan-shaped leaves. During our Skeleton Coast trip, we bought a few makalani palm nuts by the roadside to bring home as inexpensive souvenirs. These cute clumps of “plant ivory” were transformed into small pieces of handcrafted art by some local carvers. You can also find traditional ornamental bowls and baskets hand-woven with makalani palm leaves.

Ephemeral rivers and underground streams are important water sources for the local wildlife. These linear oases offer the best opportunity for game viewing in the Skeleton Coast National Park. You can often spot springbok and oryx antelopes grazing on lavish vegetation along the riverbeds. But be warned about the lions roaming the area. While staying in Terrace Bay for a night, we were told about these big cats frequenting the coast. You can track their movements around the Obab and other Skeleton Coast rivers on the “Desert Lion Conservation” website.

Skeleton Coast Marine Plants and Seaweeds

Seaweed Cast on Skeleton Coast

The outer part of the Skeleton Coast National Park is dominated by sandy beaches, with occasional rocky outcrops. The Benguela Current supplies large amounts of nutrients, feeding both marine animals and fields of seaweeds along the coast.

Although the diversity of the local sea flora is not as high as in the neighboring South Africa, it is considerably richer than in Angola and other countries of the West coast of the continent. A significant number the Namibian algae species are considered regional endemics to Southern Africa and the Benguela Marine Province (28.1% and 12.8% of flora, respectively). However, out of 196 described species, Acrosorium cincinnatum is the only endemic algae to Namibia. In addition to Swakopmund area, it has been found in Terrace Bay, Möwe Bay and at the Rocky Point in the Skeleton Coast National Park.

The seaweed variety along the Skeleton Coast features brown (Split-fan kelp or Laminaria pallida), green (Sea Lettuce or Ulva spp.) and red algae (Cape laver or Porphyra capensis, Red ribbons (Suhria vittata)). The epiphytic Yellow skin (Aeodes orbitosa or Pachymenia orbitosa) is more prevalent along the southern Namibia, where, in the sheltered waters, the size of its thallus (“leaf”) can reach 1-1.5 m in diameter. However, it has also been reported at Cape Frio and other locations of the Skeleton Coast.

Check out the “Marine benthic algae of Namibia” article for an overview of the Namibian seaweed variety and their geographic distribution, including those sampled in different locations along the Skeleton Coast.

The growth rate of algae in this part of the Atlantic Coast is one of the highest in the world. Some varieties (Laminaria pallida, Gracilaria verrucose) have been harvested in Namibia for commercial and domestic purposes.

Economical uses aside, seaweeds play an important ecological role along the Skeleton Coast. They serve as both food and shelter for marine and shore animals living in the inter-tidal zone. Swells and wind wash large amounts of seaweeds ashore. These plants decompose and provide nutrients to the soil-deprived sandy beaches, which dominate the Skeleton Coast National Park.

Rare and Endemic Plants of the Skeleton Coast

Nara Plant with Fruits

Nara plant (Nara melon or Acanthosicyos horridus) and Welwitschia mirabilis are unusual long-lived perennial plants and are both botanic curiosities of sorts. Despite their Namib Desert endemic status, neither is currently endangered (although Welwitschia does have a “protected” status in the country) because they are well adapted to their environment and are relatively common within their natural habitat.

Nara melon is a dune-growing Cucurbitacean plant, which forms dense bushes with branched light-green spiny stems and pale-yellow solitary flowers. The green fruits are also thorny and turn yellow or pale orange when ripe. They are not true desert plants and grow mostly in areas with underground water sources. Nara plants are far more ubiquitous in the Namib Sand Sea south of Swakopmund (the Sossusvlei and Sandwich Harbor are among the best viewing spots for this ecologically important desert species).

Welwitschia mirabilis is not as commonly seen along the Skeleton Coast as in other parts of Namibia. However, it can be found, if you know where to look. Check out where wild Welwitschia mirabilis grows post for 2 such locations near Ugab and Springbokwasser Gates of the Skeleton Coast Park.

Male plant of Welwitschia mirabilis

The majority of endemic and rare plant species of the coastal Namib Desert grow in the Sperrgebiet area (German for “forbidden territory”) further south. It is a part of a larger Succulent Karoo Region of the Southwestern Africa, one of the few recognized hot spots in the world with exceptional biodiversity.

Nonetheless, several Red Data Book plant species also live along the Skeleton Coast. The list of local endemics includes Aloe dewinteri Giess (Sesfontein-aalwyn), a smaller population of Cyphostemma juttae (a Cissus species) and a larger woody perennial plant Elephant’s Foot (Adenia pechuelii).

The upper part of the Skeleton Coast represents the northern limit of the natural habitat for peculiar dwarf succulents Lithops (Mesembryanthemums, also called “flowering stones” or vygies, locally). These regional endemics live almost exclusively (98% of all species) in the Succulent Karoo Region of Southwestern Africa. A few lithop species found outside of this region are believed to be dispersed and introduced there by shorebirds. Lithops ruschiorum, a Red Data Book endemic with a long-lasting yellow flower, lives in the Skeleton Coast National Park.

Lithops’ very short stem with a couple of thick fused leaves are sometimes barely visible in the sand and pebble ground cover. This peculiar appearance is an adaptation to the extremely dry environment. It allows for a reduction of surface area, while maximizing the leaf volume for water storage.

The most remote northern part of the Skeleton Coast is only accessible with fly-in tourist operators. In addition to the rare plants mentioned above, “cactus-like” stapeliads Hoodia currori, towering over the desert landscape, and Hoodia pedicellata (Trichocaulon pedicilfatum) can be spotted there.

This is also the natural habitat for the Namibian population of Adenium boehmianum. This plant is also called Bushman Poison, because the Heikom Bushmen apply its poisonous sap to their arrowheads for game hunting.

Unfortunately, poaching by succulent collectors and commercial dealers represents one of the biggest threats to these rare plants. You can learn more about Namibia’s threatened or endangered plants from this well illustrated on-line book “Red Data Book of Namibian Plants”

by mytravelcurator | May 5, 2019 | Africa, Namibia

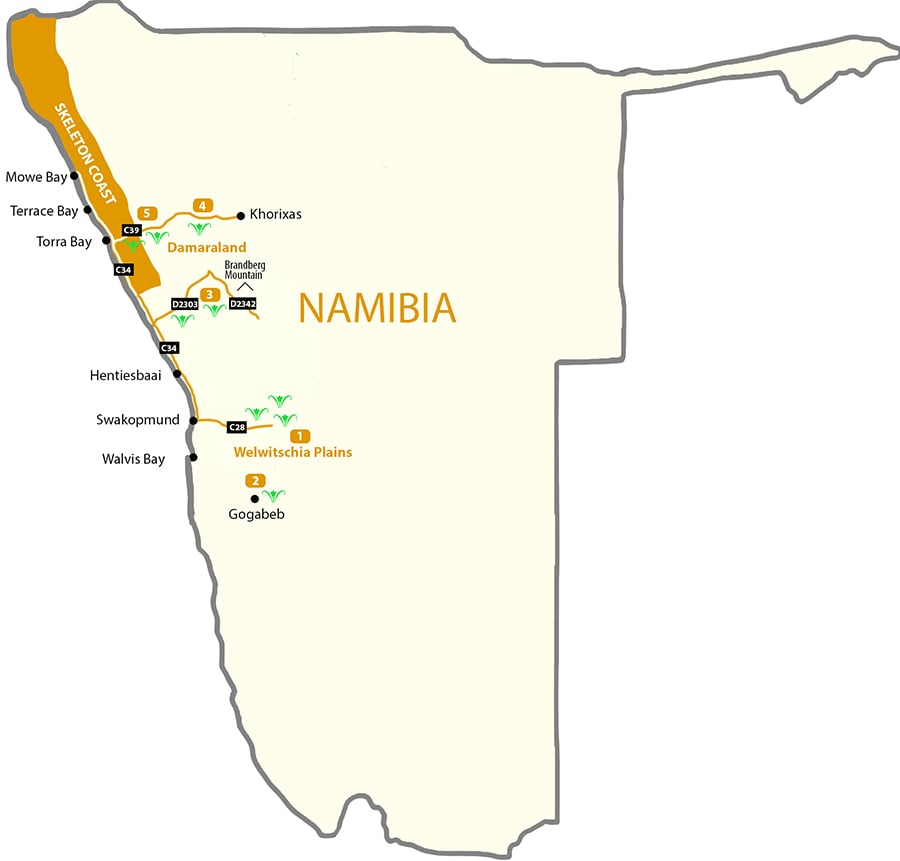

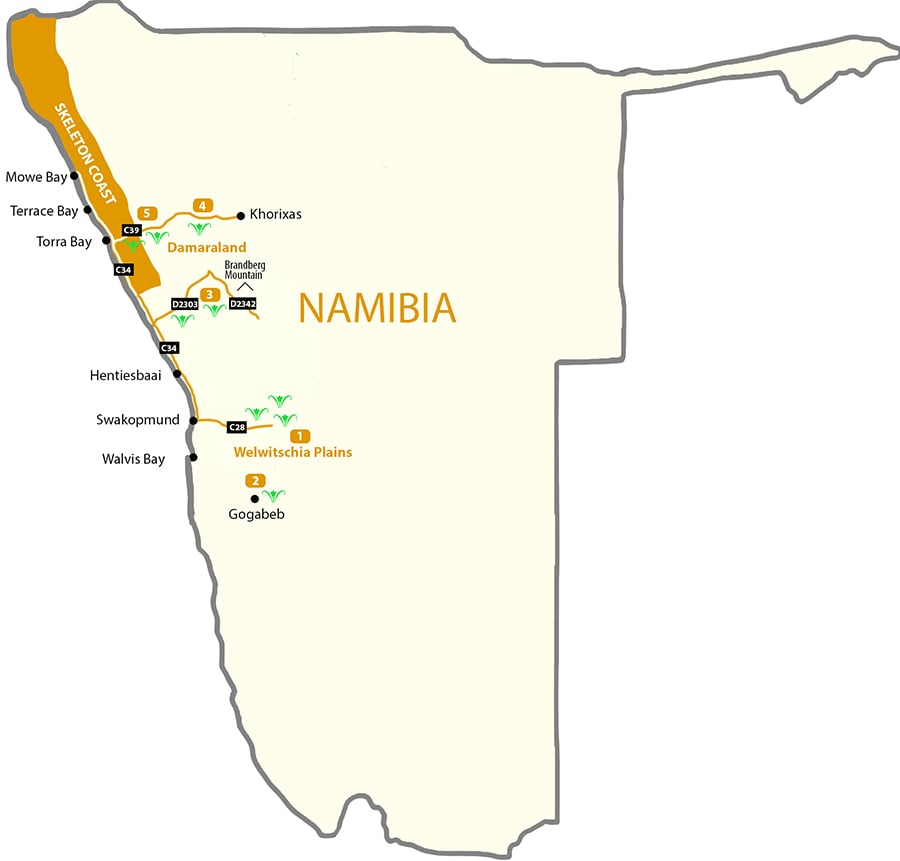

The Welwitschia Plains near Swakopmund and the Coastal fog belt of Damaraland are the areas with most reported sightings of Welwitchia mirabilis since its discovery in Namibia. Below is an abbreviated map and detailed descriptions of 5 specific locations in Namibia, where you can find larger populations of Welwitschia plants in the wild. Most of them are based on our own sightings during the Unexpected Trip to Africa.

Discovery of Welwitchia mirabilis in Namibia

In September 1859, an Austrian botanist Friedrich Welwitsch made the first documented discovery of a new remarkable plant living on an elevated plateau near Cape Negro in Angola. He shared his findings with Dr. William Hooker, the director of the Royal Botanic Gardens, Kew at the time.

Shortly after, 500 miles south, Thomas Baines, an artist who was accompanying Dr. Livingstone on an expedition to the Zambezi River, drew several colored sketches of a big mysterious plant he found in the Namib Desert. Along with a few cones and leaves he collected, Baines sent his drawings of the “strange giant aloe” to William Hooker as well. This marked the official discovery of the “marvelous plant” Welwitschia mirabilis, in Namibia.

Today, you can see an oil painting created by Baines based on his original sketch at the Kew Library. Its caption reads “The Welwitschia mirabilis or Nyanka Kykamkop plant of Hykamkop, South West Africa. T. Baines. May 9 1861”.

Map of the best viewing locations of Welwitschia mirabilis in Namibia

Welwitschia Mirabilis Natural Range and Distribution

Welwitschia mirabilis is a regional endemic of the Coastal Namib Desert. Its natural range extends over an area of 150,000 square km along the southwestern coast of Africa from the Kuiseb River (the Tropic of Capricorn) in central Namibia to the Bentiaba River in southern Angola. Its preferred habitat appears to be hyper-arid gravel plains or gypsum-rich soils.

The prominent Swedish explorer of Namibia Charles Andersson was writing in his notes “It is most common about the lower course of the River Swakop”. He also mentioned that it was growing in “the ground of hard quartzose character, and generally near little ruts worn in the plain by running water in the rainy season”. In 1862, the first living specimen of Welwitschia mirabilis was planted “with its native soil in a flour barrel” and shipped with a mail-steamer to join the botanical collection at Kew.

Below are five best locations in Namibia to see a variety of wild Welwitschia mirabilis plants growing within distinct, but equally natural habitats (numbered as on the map above).

1. Welwitschia Drive

The location the explorer Charles Andersson was referring in his early notes is believed to be Welwitschia Plains (also called Welwitschia Flats or Welwitschia Fläche). It is the most popular and widely advertised site in the Central Namib Desert for viewing Welwitschia plants. Situated between the Khan and Swakop rivers, it is a part of the Namib-Naukluft Park and has an easy access both from Swakopmund in the west and Windhoek in the east.

Typical landscape of the Welwitschia Plains

A permit, which can be obtained in Swakopmund, is required to access the Welwitschia Plains. With this permit, you will also receive a hand-drawn map of the Namib-Naukluft Park containing the small section dedicated to the Welwitschia Drive.

The tourist route from Swakopmund through Welwitschia Plains is called Welwitschia Drive. The round trip is 160 km and takes about 3-4 hours to tour with stops. It is an arid and barren place, but the area by the Swakop river provides some shade and is equipped with picnic tables and even campsites for overnight stays if desired.

You can download and bring along the official “The Welwitschia Plains – scenic drive” brochure, which includes a map and descriptions of all “attractions” along the route. Look for 13 labelled stone beacons. At the end of the Welwitchia Drive at the turning point, markers 11 & 12 will indicate the highlight of the trip, a larger group of very special Welwitschia (some female and male plants are marked with respective signs).

The Swakopmund location along the Welwitschia Drive boasts the oldest known plant colony, some of which are of remarkable size. The two largest Welwitschias (both female plants) in existence are growing here. These are also the oldest living Welwitschia plants, with an age of 1500 years (as estimated by carbon dating).

Chris Bornman details the enormous size on these peculiar plants in his article “Welwitschia mirabilis: paradox of the Namib Desert”: “The two tallest plants known, the Husab Welwitschia and the Pforte Welwitschia are 1.5 m and 1.9 m from the base to crown, respectively. The latter plant occupies an area 9.1 m in circumference and its stem, measured along the terminal groove, has a circumference of 5.7 m”.

Local mining activities resulted in excavation of some old Welwitschia plants in the area. This facilitated a study of their root system and the water sources. It showed that, contrary to a belief, the tap root was not all that long and did not measure more than 3 meters. Based on these and other observations, it was concluded that Welwitschia plants cannot rely on access to the ground water at 50-75 m depth for water supply.

2. Mine Hope and Welwitschia Wash on Kuiseb River

View of the Kuiseb River in dry season

The Tropic of Capricorn is the most southern frontier of Welwitschia mirabilis natural habitat range. This community of plants is little off the most popular tourist routes in Namibia, but it may be more accessible if you plan to visit the Gobabeb Research and Training Centre (GRTC). The Center, which is located about 120 km southeast of Swakopmund, has dedicated numerous studies of the Gobabeb population of Welwitschia mirabilis.

These plants are concentrated in tributaries of the Kuiseb River, 15 km (in the Welwitschia Wash) and 30 km (near the Hope Mine) from the Research Center. Apparently, you can make a reservation for your stay in the area by directly contacting the GRTC.

Welwitschia Plants of Damaraland

Unlike Welwitschia Plains near Swakopmund, the Welwitschia locations of Damaraland and the neighboring Skeleton Coast are not widely advertised. This may be because many of these places are more remote and some are notoriously difficult to get to. Below are the three areas in the Damaraland you might wish to explore in search of Welwitschia mirabilis.

Damaraland landscape

3. Welwitschia of Brandberg and Messum Crater

Amid vast desert plains, 250 km north the Welwitschia Drive, there is a granite massif with Namibia’s highest peak, the Brandberg Mountain (2,573m). It is at the foot of this mountain, Willie Giess (a botanist who was mapping Namibian plant communities back in the 1970s) found the largest Welwitschia plants ever recorded. Reportedly, he described a plant with a stem height of 1.8 m and another one with a stem diameter of 4 m near the Messum Crater (a large volcanic depression in the ground) west of Brandberg. However, some publications indicate that those giants since then burnt down by the lightening fire.

Unique Welwitschia plants with extra leaves (3-4, instead the usual 2) were also reported around here by Dieter von Willert in 1993. Two distinct types of extra-leafed Welwitschia were described in “Can Welwitschia mirabilis have more than only two Foliage leaves?”.

The first type had an additional pair of opposite leaves breaking through the top of the stem (more than a dozen of these were found among the 300 plants examined). The second variety had a single additional leaf. A group of nature enthusiasts on a follow-up “expedition” to this area in 2001 confirmed these findings. You can read their own account in “Torn to Ribbons in the Desert”.

A check list of 490 vascular plants living in the area (including Welwitschia mirabilis), can be found in “The flora of the Brandberg, Namibia”.

The Brandberg and Messum Crater area is best accessible via D2342 and D2303, off the Skeleton Coast road C34. Both D-roads are in a relatively good condition and are passable by a 2WD (although renting a car with higher clearance is advisable in these parts).

This amazing travel blog describes an adventurous 3-day journey of a biker along the same route (albeit in opposite direction) D2342 and D2303. There are also numerous photographs of the area, including those of the Brandberg Welwitscha population.

Ugab River Rhino Camp near the D2342-D2303 junction is the only place in the area where you can camp. However, you can visit the area as a day trip from Hentiesbaai (if you start early) or better yet from Cape Cross on C34.

Driving along the northern section of D2303 over the Ugab River is not recommended for independent tourists even by a 4WD. It is easy to understand after you hear the story about a well-travelled Dutch couple, Jan Snel and Mieke Schrijver, who got lost in that remote Burnt Mountain region of Damaraland and ran out of fuel in the late April 2003. They were stranded there without water for over two weeks. By the time they were found, Jan Snel died of dehydration and his wife was barely alive.

4. Welwitschia on the Fringes of the Skeleton Coast

Welwitschia grow along roadside of C39 just before you exit the Springbokwasser Gate of the Skeleton Coast National Park (30km from the Atlantic Coast). Curious about other unique plants along this route? Read the Skeleton Coast Plants post.

As you continue along beyond the Gate, a scenic view over the gravel plains opens up with numerous additional opportunities to get spectacular local welwitschia plants in the frame with the mountains of the Great Escarpment as a backdrop. These plants are “fed” by the water provided by the Koigab River, which “runs” faithfully along the road.

Male and female Welwitschia plants on gravel plains of Damaraland

If you keep driving for another 125 km on C39 (about 2 hours) from the Skeleton Coast National Park), you will be able to admire Welwitschia plans thriving in a different natural environment of the mopane savanna.

5. Welwitschia in Mopane Savanna near Khorixas

This unique population of Welwitschia plants grows along C39 west of Khorixas in Damaraland. The mean annual rainfall (150–200 mm) is significantly higher here than in the other Namibian Desert Welwitschia habitats described above. This is mopane savanna dominated by extensive grass cover, small shrubs and mopane trees.

If you are headed to see the Petrified Forest (45 km west of Khoraxis on C39), you won’t be able to miss the local Welwitschia growing there. They can be spotted rooted in sandstone right next to the 250 million years old fossilized pine trees, which are the major attraction of this site with the national monument status since 1950.

Mopane Savanna Landscape of Damaraland

by mytravelcurator | Apr 27, 2019 | Central America, Costa Rica

One does not have to be a hard-core birder to enjoy bird-watching at Los Cusingos Neotropical Bird Sanctuary, just as

“One needs no scientific training to love a warbled song, or to warm to the sight of a parent bird bravely defending its helpless nestlings”

Skutch A.F. from Untitled, Journal, 1931

During a recent visit to Southern Costa Rica, we were looking into some unusual places for nature walks along Interamericana Highway (designated as Route 2 on the maps). We found Los Cusingos Bird Sanctuary to be such a place, with a long bird checklist (at the bottom of this post) and full of character.

Nesting Bronzy Hermit

The Bird Sanctuary covers 78 hectares, of which 50 ha. is primary forest and the remaining 28 ha. secondary growth. It has Dr. Skutch’s house-museum, a cabin and a small visitor center. The garden has a variety of marked native and exotic plants and trees. It also has a small nursery with flowering plants (including local orchids (some of them so tiny, that only high-quality macro photographs would make them full justice).

Why is Los Cusingos Worth a Visit?

The allure of the Los Cusingos is easy to understand once you know the story behind it. Even if you don’t, there are many reasons to spend a day or two at this place:

- Los Cusingos is the only sizable lowland premontane forest area with primary growth near San Isidro del General. The rest has been logged down without a trace.

- Over 300 bird species have been reported at Los Cusingos over the years

- Skillful and knowledgeable nature tour guide on site

- A bird feeding station is available for independent visitors on self-organized tours

- Los Cusingos is Alexander Skutch’s Home (now a museum and a resting place)

- Enjoy Pamela Lankester’s Garden with marked plants and trees and a small nursery on site

- See agouties, coatis, snakes and other wildlife in their natural habitat

- Well-preserved Indian petroglyphs dated back to Pre-Columbus time at the end of a trail

- Easy access from San Isidro del General (or, better yet, by staying locally in Quizarra)

- Easily walkable terrain and trails

Agouti frightened by a Coati

Birds of Los Cusingos

According to the census conducted the Tropical Science Center (which oversees the sanctuary), the avifauna of Los Cusingos counts over 307 species, half of which were resident birds. The bird sanctuary covers altitudes between 650 and 750 meters above sea level. Across the Talamanca Mountain Range, the variety of avian species changes with altitude. Thus, Los Cusingos makes a perfect location for watching birds, which prefer lowland and mid-elevation habitats.

Guided Bird-watching Tour in Los Cusingos

Our Local Guide at Los Cusingos

Our guide, a humble local guy J. Andres Chinchilla, was recommended to us by our Airbnb host in Quizarra. From the very beginning, he was responsive to our requests and generous with his time. You can contact cusingos@cct.or.cr to connect with Andres.

Being born and brought up locally, Andres worked for Alexander Skutch himself since he was 14. He actively participated in construction of the walk trails and other improvement projects at the Sanctuary. His dream is to supplement his tour-guiding job with building a few cabins locally and to expand his ecotourism-oriented business.

Slaty-tailed Trogon at Los Cusingos

Early Morning Bird-watching Tour

We met at the gate bright and early, before the Sanctuary “gates” even opened (another advantage of staying locally and going with a local guide). Equipped with a high-quality Swarovski scope and intimate knowledge of Los Cusingos native and migratory birds, Andres spent almost 6 hours birdwatching with us. “Patience is a virtue of a lucky birder”, he remarked to us, while setting up his scope in the garden and taking out a couple of bananas out of his backpack.

Female Honey Creeper at the feeder

If you do not have a tour guide, you can still use a bird feeding station by the garden to observe a variety of birds. Just remember to bring a few ripe bananas for this purpose. During our visit, Speckled Tanagers, Shining Honeycreepers and Green Honeycreepers, Spot-crowned Euphonias and Cherrie’s Tanagers were not shy at the feeder.

Along the edges of the garden, we also observed the famous Fairy-billed Aracari, Red-capped Woodpecker, several species of Hummingbirds and a Blue-capped Manakin gulping dark-blue fruits of melastomes in the air. That morning, we were also lucky to get a fleeting glimpse of the endangered Turquoise Cotinga.

Peñas Blancas River

After spending a couple of hours in the garden, we started walking by the Peñas Blancas river and along the River trail. At the entrance of the Naturalist trail, the forest got denser and more mysterious, dominated by tall mossy trees covered with epiphytes, climbing woody vines and walking palms on spiny “stilts”. On the go, Andres spotted several elusive resident birds and got them on the scope and “in the frame” for us. By the time we circled back to the garden, our bird list grew substantially longer and included Blue Dacnis, Riverside Wren, Baird’s Trogon and Orange-collared Manakin. If you have specific the bird species on your wish-list, let Andres know and he will make you bird checklist glow with new entries within a short time.

Alexander Skutch House-Museum

Having spent a few hours birding, we could now immerse ourselves into the history of Los Cusingos and the fascinating life story of its former owners Alexander Skutch and Pamela Lankester. The House (now a museum) was built by Alexander Skutch himself and has changed little since the time the homesteading naturalist settled down there.

Alexander Skutch’s study

Browsing through the simply appointed rooms, one can easily sense the Skutch’s appreciation of a humble lifestyle and “work environment”. The original old typewriter, which was used for decades to capture his notes, articles and book manuscripts was still resting on his desk. The sturdy self-built wooden bookcase was fully loaded with “well-used” ornithology guide books and Skutch’s own volumes authored during his 60 years-long ornithology career. The man, who objected to banding or handling birds, let alone collecting them, came up with creative ideas for learning about them by mere observation. Some of his “inventions” are on display in his study along with his old binoculars and cameras.

Coffee with a View

After the walk and an insightful conversation with two other birding enthusiasts (the only other visitors we met at the Sanctuary that Sunday morning), we asked Andres about any local cafe nearby in Quizarra. He immediately hopped into his car and told us to follow him.

The local bakery, just a few hundred meters away, had two tables and a magnificent view. The variety of freshly made pastries in this little place was just too wide for us to navigate through. At the end, we settled for a couple of Andres’s favorites, a cup of famous Costa Rica-grown coffee and sat down to enjoy the vista over Valle del General.

View of Valle del General from the Bakery

Birdwatching North of Los Cusingos Bird Sanctuary

The northern section of the Alexander Skutch Biological Corridor is located at higher altitudes of Las Nubes Biological Reserve. It is bordering the Chirripó National Park and reports a large variety of avifauna, including several of the 28 described restricted-range regional endemics of the Talamanca Mountain Range. Long-tailed Silky-flycatcher (Ptilogonys caudatus), Black-faced Solitaire (Myadestes melanops) and Sulphur-winged Parakeet (Pyrrhura hoffmanni) are just a few examples.

A recently published book “Birds of the Alexander Skutch Corridor, Costa Rica” is a great resource, if you are interested in learning more about the avifauna of the entire Alexander Skutch Biological Corridor. This field guide covers 285 bird species recorded by the Faculty of Environmental Studies of York University (Toronto, Canada). The long list of birds includes 47 migratory species, 41 altitudinal migrants, 23 endemic species, and 11 near threatened or vulnerable species.

Los Cusingos Bird Sanctuary – Bird List

by mytravelcurator | Apr 19, 2019 | Central America, Costa Rica

Zamia is the only living genus of cycads native to Costa Rica. The most recent reports include 5-6 Zamia species (depending on the source), two of which are described by cycad experts as endemic (E).

- Zamia fairchildiana

- Zamia pseudomonticola

- Zamia acuminata (E)

- Zamia gomeziana (E)

- Zamia neurophyllidia

- Zamia obliqua

What are Zamia?

Zamia is a group of plants endemic to the New World (only live in the Americas). The first one identified was officially named Zamia pumila by Carl Linnaeus back in 1762. At that time, some West European botanical gardens (such as those in Leiden and Amsterdam) already had some specimens acquired during expeditions to the West Indies.

Costa Rican Zamia fairchildiana

How many Zamia in Central America?

79 Zamia species have been described and the list is constantly growing. Their present range spans most of the tropical Americas, from southeastern Georgia and Florida down to northern Argentina. In Costa Rica, Zamia grows on both the Pacific and Atlantic coasts.

Despite Costa Rica’s status as a biodiversity hotspot in Central America (and in the world), its cycad list is relatively short. In contrast, neighboring Panama (of a similar size to Costa Rica), has at least 17 different living Zamia species. Moreover, a huge variety of cycads has been described in Mexico (62 cycad species, including 17 Zamia). Nicaragua, on the other hand, has a single Zamia species (Zamia neurophyllidia), which is also “shared” with Panama and Costa Rica!

Zamia Biodiversity Hotspot or Not?

Puzzled by these differences, I have investigated and found a recent biogeographic Zamia study by an international group of scientists. This team analyzed the genetic “relatedness” of 70 American Zamia species using leaf DNA samples from Cyclades plants of known origin (found in the wild or from botanical collections). By doing so, they were able to organize them in 3-4 related clusters.

According to the Zamia distribution map in a recent publication, there is a large “dead zone”, with no known living Zamia species. The gap covers most of Nicaragua, El Salvador and Honduras and separates the Mesoamerican group (which includes Mexico) from the Central American group (includes Costa Rica as its northern “frontier”).

Despite the numeric differences between Costa Rica and Panama in Zamia species, it is still reasonable to consider both countries as “biodiversity hotspots” for Zamia in terms of species density. See the diagram of Zamia species richness across South and North Americas.

Where to Find Zamia in Costa Rica

If you’d like to find Zamia fairchildiana and the closely related Z. pseudomonticola and Z. acuminata in the wild, the humid lowland and mid-elevation areas (up to 1600 m) along the Pacific Coast of the country would be the best spots. Most of the collected “plain-leaflet” Zamia samples and reports originate from the Puntarenas Province (Osa peninsula, San Vito area, La Amistad NP) and some areas of the bordering San José and Alajuela provinces.

The “pleated-leaflet” Zamia neurophyllidia (referred to as Z. Skinneri by older reports) with distinctive broad veined leaflets, has only been found on the Atlantic Coast of the country.

Zamia Collections of Wilson Botanical Garden and Finca Cántaros

Wilson Botanical Garden Cycad Collection

The easiest way to see Costa Rican Zamia cycads (the most common varieties) is to visit the Wilson Botanical Garden in San Vito. Although more known for its world second largest collection of palm trees, it also has a variety of Asian, African, Australian and American cycads. Many of the cycads in the botanical garden are large mature plants and several had either female or male cones “on display” during our January visit.

On our recent trip to Southern Costa Rica, we have also found plants of Zamia fairchildiana in the “Zamia Zone” of the gorgeous private gardens of Finca Cántaros (open to the public). This small “nature reserve” is located just a couple of miles away from the Las Cruces Biological Station and the Wilson Botanical Garden and is well worth a 1-2 hour visit.

Costa Rican “Cycad List” in Flux

The original Costa Rican cycad taxonomy was compiled by Luis Gomez in 1982, a prominent Costa Rican botanist and former director of Museo National of Costa Rica and Las Cruses Biological Station and Wilson Botanical Garden. It listed 6 species, including the only known epiphytic (growing on trees) form of Zamia, Z. pseudoparasitica. That species was never confirmed living in Costa Rica and is considered a Panama endemic. Z. chigua has been removed from that list. Moreover, the Costa Rican Z. skinneri has been reclassified into the closely related Zamia neurophyllidia.

Recently Discovered Costa Rican Zamia

The relatively new species of Zamia gomeziana (similar in appearance to the Zamia species of the Pacific slope) was found on the Atlantic coast in Limón Province in 2010. The new species has been so far represented by a single female plant, but the hopes are still high to find more samples in the same remote region bordering Panama.

Reading the story of this new Costa Rican Zamia, brought back the memories of the “loneliest cycad in the world” (we stumbled upon in the Kirstenbosch Botanical Garden, while visiting Cape Town in South Africa). Only a single male plant of this species (Encephalartos woodii) was ever found in the wild. However, one hundred years later, close to two hundred individual plants grown from the original cycad can be found today in various botanical gardens and even in some private collections around the world. Despite its much more modest looks in comparison to E. woodii, there is still a hope that Zamia gomeziana will not disappear without a trace.

Z. gomeziana’s name was dedicated to the prominent Costa Rican botanist Luis Diego Gómez after his passing in 2009. In addition to the original classification of the Costa Rican cycads, Dr. Gomez made a remarkable contribution to “mapping out” and describing countless plant species of the country. He also served as a director of the National History Museum in San Jose and the renowned Las Cruses Biological Station in San Vito. Under his tenure, both institutions (including the Herbario Nacional) flourished and attracted wide attention and support from the international scientific community.

“Pick Your Poison”

Hairstreak butterfly larvae gorging on zamia

During our visit of the Cycad section of the Wilson Botanical Garden, we could not help but notice the bright-colored caterpillars gorging on zamia leaflets. Like most other cycads, Costa Rican zamia are poisonous to animals and humans. However, it is not toxic to these larvae of of White-tipped Cycadian (Eumaeus godarti), a small colorful Hairstreak butterfly, which prays on leaves and cones of Costa Rican zamia.

Despite the damage to the plants, some experts believe that this butterfly and Zamia might be in a mutually beneficial relationship called “opportunistic semi-mutualist symbiont”. I know, it is a mouthful for the most of us. By eating the “casing” of mature female cones of zamia, but leaving the seeds intact, the larvae might help cycads to disperse their seeds and to speed up the germination process.

As for the poison, the insects store and use the ingested toxic substance produced by Zamia against their own enemies, who will think twice before grabbing their dinner. Those bright colors of the larvae are just the “keep-off’ signal to their potential predators.