Skeleton Coast Plants – More Than Meets the Eye

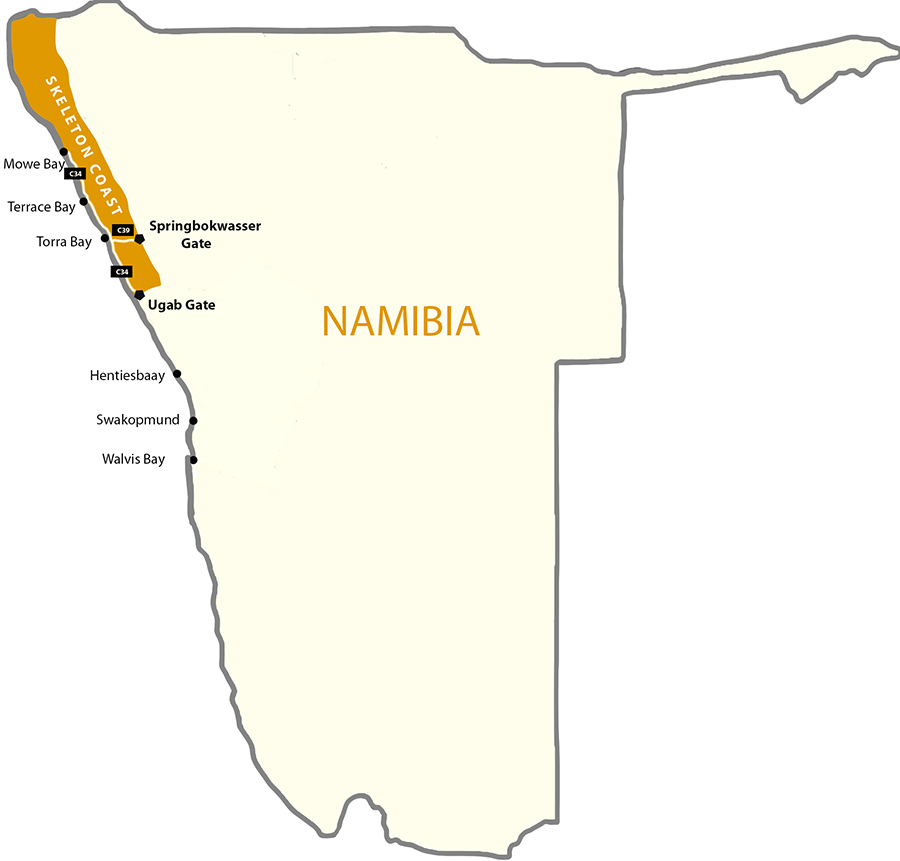

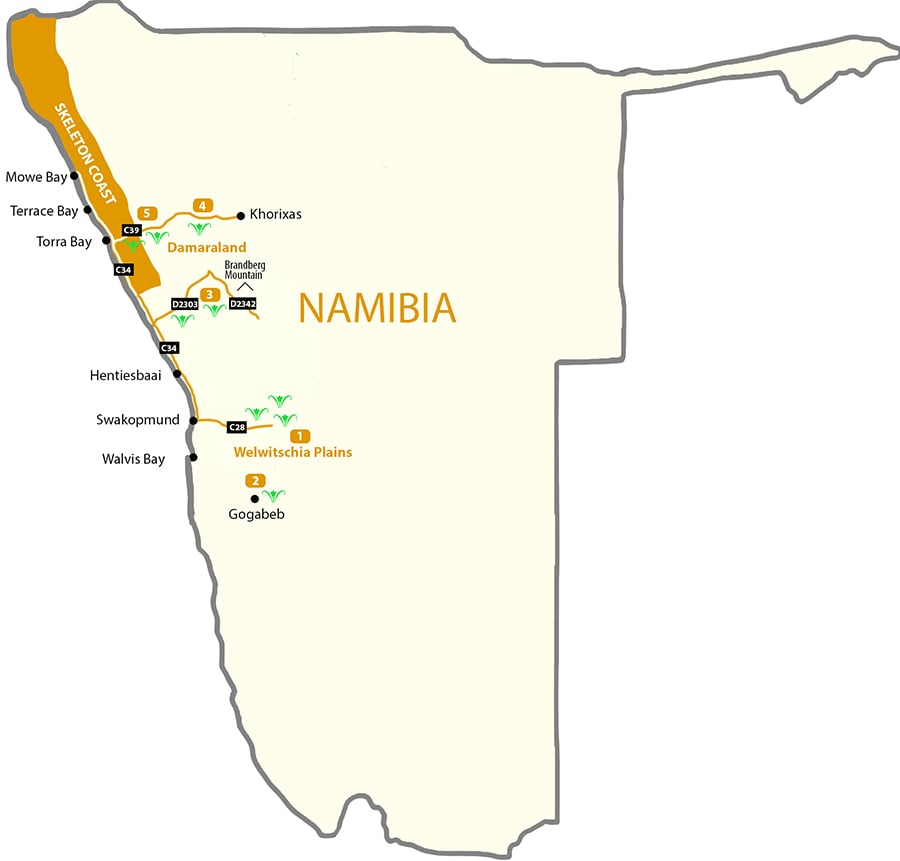

The harsh and uninviting environment of the Namibian Atlantic Coast sparked our curiosity about its plants. On our springtime self-drive trip to the Skeleton Coast National Park, we got surprised by the variety of vegetation found there.

The Skeleton Coast of Namibia is dominated by several unique types of vegetation, each of which thrives in a specific habitat niche:

- Lichen fields, with over a hundred different species, some of which are rare and range-restricted to this area

- Salt– and brackish water-resistant dwarf shrubs and small trees abundant along the coast covered by sea salt and periodic salt-pans

- Seaweeds, with growth rates among the highest in the world, abundant along the coastline and include regional endemics of Southern Africa and the Benguela Marine Province

- Succulent and non-succulent desert-adopted plants of various sizes

- Grasses, tall shrubs and small trees common along the ephemeral riverbeds and underground streams

Skeleton Coast Climate and Water Sources

The Namib Desert is one of the driest places on Earth, with an average annual precipitation of about 2 cm along the Skeleton Coast. And some years, it does not rain at all. There are only two other coastal deserts in the world with a similar climate: the Atacama Desert on the Pacific Coast of Peru and Northern Chile, and the Sonoran Desert in Baja California. Unsurprisingly, there are significant similarities in vegetation patterns between those arid places and the Namibian Skeleton Coast. Many of their native plants and lichens also rely heavily on the coastal fog and dew as main water sources.

1. Fog vs. Rainfall

Despite the low to non-existent rainfall, the cold Benguela Current of the Atlantic Ocean by the Namibian shore brings over cool, moist fog on most days of the year (especially in the winter months). This dense atmospheric moisture is pushed further inland by the wind, where it disappears around noontime. This phenomenon keeps the average air humidity levels relatively high, within the Namibian fog belt.

The amount of fog moisture blown by the westerly wind through the coastal part of the Namib Desert is typically between 4-9 cm per year, which far exceeds the average rainfall precipitation (of 2 cm). Coastal fog is a source of not only moisture, but also nutrients. Moreover, it plays an important role in the formation of gypsum crust, which is a critical substrate for the “pioneering” lichen growth. See more information on gypsum-rich soil below.

2. Morning Dew

The annual average temperature on the Skeleton Coast is only 16 °C, with wild fluctuations between day and night. Because of these changes, the dew precipitation is significant in these parts of the world. Like fog, dew moisture is an important direct and indirect (through soil drip) water source for the wide variety of lichens and some succulent plants in this hyper-arid region.

3. Ground Water

In the Southern Namib Desert, almost no rivers reach the Atlantic Coast most of the year. In contrast, the ephemeral rivers cutting across the Skeleton Coast do form lavishly green linear oases throughout the otherwise desolate coastal desert landscapes. Some of these rivers and streams are completely hidden underground, but the water still sips through the surface bringing the desert landscape above the ground to life. River water is a lifeline for grasses, trees and the browsing wildlife.

Skeleton Coast Vegetation Pattern

As we traveled along the Skeleton Coast, we noticed that the vegetation varied wildly between the outer coastal areas and its interior. The outer zone of a few hundred meters was covered with low-growing succulent shrubs, such as the Namib endemic Dollar bush (Zygophyllum stapfii). Its Red book restricted-range relative Zygophyllum inflatum grows in the most northern section of the Skeleton Coast Park. Archaeological studies on the Skeleton Coast indicate that Dollar bush plants served as a major source of charcoal for the seasonal settlements of the local Namibian tribes in the past. Following the dry riverbeds, they were coming from the “hinterlands” of the Kaokoland to make use of the marine food resources available by the ocean.

Other salt-tolerant shrubs, such as Ganna or Saltbush (Salsola species) and Pencil bush (Arthraerua leubnitziae) also thrive along the sandy beaches of the Skeleton Coast Park. These plants trap sand particles forming sand hummocks, which provide habitat for local wildlife and form larger dunes over time.

The dominance of lichens throughout the Namib Desert is epitomized along the plains of the Skeleton Coast. Large sand dune-free areas, called “lichen fields”, stretch along route C34 on the Skeleton Coast road. The fog belt, with the moisture not available to most vascular plants, makes for perfect lichen living conditions. They grow on gravel surfaces and gypsum-crusted soil and become dormant (but do not die) when moisture is not available.

The gravel plains on the eastern edges of the Skeleton Coast are reminiscent of the Damaraland shrub lands, dominated by larger populations of Milk bush (Euphorbia damarana) and a few low-growing trees.

Lichen Fields of the Skeleton Coast

The ability of lichens to survive on coastal fog and dew alone and to “cycle” between the dormant and active states make them perfectly adopted to the Skeleton Coast environment. Here, they are rich in species (although many are closely related) and the endemism level is impressive. Still, some species (e.g. Santessonia namibensis) living here are believed to have the smallest distribution ranges of all lichens in the world.

The first descriptions of Namibian lichens were published over one hundred years ago in “Die Pflanzenwelt Deutsch-Südwestafrikas”. Since then, over 100 lichen species living in the Namib Desert alone have been described (if you are looking for a field guide, check out “Lichens of the Namib Desert“ by Dr. Volkmar Wirth).

Given their microscopic size, the amount of “lichen biomass” along the Skeleton Coast is also impressive. For some “lichen fields”, it is reported being as high as 400 grams per square meter. The biological soil crusts they form in this hyper-arid land makes lichens the key flora of the Skeleton Coast.

Lichen fields are complex and fine-tuned ecological systems. Many environmental factors, such as moisture levels, soil acidity and salinity, availability of stable substrate (sand dunes vs gypsum crust vs gravel) and even its sloping angle determine lichen growth and distribution.

The prevailing winds on the Skeleton Coast shape the pattern of the vegetation cover. If you take a closer look at the lichen-covered rocks, you will notice that the colonies prefer living on the west-facing surfaces. This is because the Atlantic Ocean brings cool moist winds, whereas the winds from the East tend to blast the vegetation without mercy with deadly hot air and sand.

A lichen fields is also a very fragile ecosystem. Once disturbed by tourist vehicles, it takes decades, if not a full century, for them to recover. Remember to stay on the road when driving through the Park!

Desert sand, which is constantly on the move, does not encourage lichen growth. In contrast, gravel stones littering the Skeleton Coast, and cemented gypsum crust serve as an excellent substrate for lichens.

Coastal fogs play a key role in the formation of the large areas of gypsum-rich soils on the Skeleton Coast. Here is how they are created, in a nutshell: H2S released by the ocean reacts with atmospheric oxygen and forms sulfate, which is then transported inland by the coastal fog, where (in the presence of calcium carbonate) it turns into gypsum (CaSO4·2H2O).

Vegetation of the Ephemeral Rivers

As we continue driving north, several dry riverbeds cut across the desert landscape. Grasses and taller vegetation, such as wild tamarisk or “salt cedar” bushes (Tamarix usneoides), mopane trees (Colophospermum mopane) and makalani palms (Hyphaene petersiana), become more common here.

Makalani palms, native to Northern Namibia, are easily recognizable by their fan-shaped leaves. During our Skeleton Coast trip, we bought a few makalani palm nuts by the roadside to bring home as inexpensive souvenirs. These cute clumps of “plant ivory” were transformed into small pieces of handcrafted art by some local carvers. You can also find traditional ornamental bowls and baskets hand-woven with makalani palm leaves.

Ephemeral rivers and underground streams are important water sources for the local wildlife. These linear oases offer the best opportunity for game viewing in the Skeleton Coast National Park. You can often spot springbok and oryx antelopes grazing on lavish vegetation along the riverbeds. But be warned about the lions roaming the area. While staying in Terrace Bay for a night, we were told about these big cats frequenting the coast. You can track their movements around the Obab and other Skeleton Coast rivers on the “Desert Lion Conservation” website.

Skeleton Coast Marine Plants and Seaweeds

The outer part of the Skeleton Coast National Park is dominated by sandy beaches, with occasional rocky outcrops. The Benguela Current supplies large amounts of nutrients, feeding both marine animals and fields of seaweeds along the coast.

Although the diversity of the local sea flora is not as high as in the neighboring South Africa, it is considerably richer than in Angola and other countries of the West coast of the continent. A significant number the Namibian algae species are considered regional endemics to Southern Africa and the Benguela Marine Province (28.1% and 12.8% of flora, respectively). However, out of 196 described species, Acrosorium cincinnatum is the only endemic algae to Namibia. In addition to Swakopmund area, it has been found in Terrace Bay, Möwe Bay and at the Rocky Point in the Skeleton Coast National Park.

The seaweed variety along the Skeleton Coast features brown (Split-fan kelp or Laminaria pallida), green (Sea Lettuce or Ulva spp.) and red algae (Cape laver or Porphyra capensis, Red ribbons (Suhria vittata)). The epiphytic Yellow skin (Aeodes orbitosa or Pachymenia orbitosa) is more prevalent along the southern Namibia, where, in the sheltered waters, the size of its thallus (“leaf”) can reach 1-1.5 m in diameter. However, it has also been reported at Cape Frio and other locations of the Skeleton Coast.

Check out the “Marine benthic algae of Namibia” article for an overview of the Namibian seaweed variety and their geographic distribution, including those sampled in different locations along the Skeleton Coast.

The growth rate of algae in this part of the Atlantic Coast is one of the highest in the world. Some varieties (Laminaria pallida, Gracilaria verrucose) have been harvested in Namibia for commercial and domestic purposes.

Economical uses aside, seaweeds play an important ecological role along the Skeleton Coast. They serve as both food and shelter for marine and shore animals living in the inter-tidal zone. Swells and wind wash large amounts of seaweeds ashore. These plants decompose and provide nutrients to the soil-deprived sandy beaches, which dominate the Skeleton Coast National Park.

Rare and Endemic Plants of the Skeleton Coast

Nara plant (Nara melon or Acanthosicyos horridus) and Welwitschia mirabilis are unusual long-lived perennial plants and are both botanic curiosities of sorts. Despite their Namib Desert endemic status, neither is currently endangered (although Welwitschia does have a “protected” status in the country) because they are well adapted to their environment and are relatively common within their natural habitat.

Nara melon is a dune-growing Cucurbitacean plant, which forms dense bushes with branched light-green spiny stems and pale-yellow solitary flowers. The green fruits are also thorny and turn yellow or pale orange when ripe. They are not true desert plants and grow mostly in areas with underground water sources. Nara plants are far more ubiquitous in the Namib Sand Sea south of Swakopmund (the Sossusvlei and Sandwich Harbor are among the best viewing spots for this ecologically important desert species).

Welwitschia mirabilis is not as commonly seen along the Skeleton Coast as in other parts of Namibia. However, it can be found, if you know where to look. Check out where wild Welwitschia mirabilis grows post for 2 such locations near Ugab and Springbokwasser Gates of the Skeleton Coast Park.

The majority of endemic and rare plant species of the coastal Namib Desert grow in the Sperrgebiet area (German for “forbidden territory”) further south. It is a part of a larger Succulent Karoo Region of the Southwestern Africa, one of the few recognized hot spots in the world with exceptional biodiversity.

Nonetheless, several Red Data Book plant species also live along the Skeleton Coast. The list of local endemics includes Aloe dewinteri Giess (Sesfontein-aalwyn), a smaller population of Cyphostemma juttae (a Cissus species) and a larger woody perennial plant Elephant’s Foot (Adenia pechuelii).

The upper part of the Skeleton Coast represents the northern limit of the natural habitat for peculiar dwarf succulents Lithops (Mesembryanthemums, also called “flowering stones” or vygies, locally). These regional endemics live almost exclusively (98% of all species) in the Succulent Karoo Region of Southwestern Africa. A few lithop species found outside of this region are believed to be dispersed and introduced there by shorebirds. Lithops ruschiorum, a Red Data Book endemic with a long-lasting yellow flower, lives in the Skeleton Coast National Park.

Lithops’ very short stem with a couple of thick fused leaves are sometimes barely visible in the sand and pebble ground cover. This peculiar appearance is an adaptation to the extremely dry environment. It allows for a reduction of surface area, while maximizing the leaf volume for water storage.

The most remote northern part of the Skeleton Coast is only accessible with fly-in tourist operators. In addition to the rare plants mentioned above, “cactus-like” stapeliads Hoodia currori, towering over the desert landscape, and Hoodia pedicellata (Trichocaulon pedicilfatum) can be spotted there.

This is also the natural habitat for the Namibian population of Adenium boehmianum. This plant is also called Bushman Poison, because the Heikom Bushmen apply its poisonous sap to their arrowheads for game hunting.

Unfortunately, poaching by succulent collectors and commercial dealers represents one of the biggest threats to these rare plants. You can learn more about Namibia’s threatened or endangered plants from this well illustrated on-line book “Red Data Book of Namibian Plants”