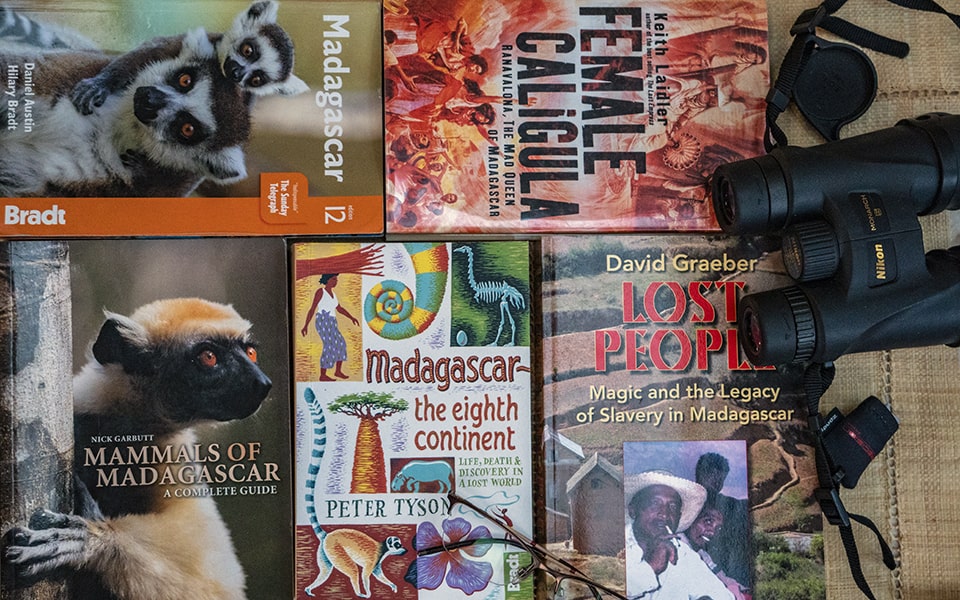

Good Books about Madagascar

Before our trip to Madagascar, we did not have the luxury of time for reading books about the Great Red Island. To find out why, check out Unexpected Trip to Africa. All we had was the expertly written Bradt Madagascar Guide Book (which we certainly recommend to any traveler, organized or independent) and a travel map. However, if you are in the habit of picking up and read a book or two about places you visit, consider one of the books about Madagascar from this list.

Favorite Reads about Madagascar

Due to its fascinating nature, Madagascar has been a magnet for biologists, anthropologists and ethnographers alike. Many of them published their notes, scientific observations and archive research findings in numerous academic articles and books. The books reviewed below became our favorites because they are educational, entertaining and easy to read. Two of them are also quite intimate in nature, as both Alison Jolly and David Graeber spent significant amount of time living within the communities they described. After reading them, the Malagasy people are more likely to appear to you as familiar soles rather than exotic human beings.

Female Caligula: Ranavalona: the Mad Queen of Madagascar

By Keith Laidler. London: John Wiley & Sons. (2005)

As Harvard University’s American History professor Laurel Thatcher Ulrich famously wrote in her research article 50 years ago, “Well-behaved women seldom make history…“. The legacy of the infamous Malagasy Queen Ranavalona appears to fit this notion. The book by the anthropologist Keith Laidler narrates a captivating story of a despotic, but rather effective female ruler. Ascending “from rugs to riches”, this pragmatic “politician” masterly governed the country for several decades.

Rather than being a simple biography of the monarch herself, the book reads as a brief artistically-written historic overview of Madagascar and the region in the 19th century. It sheds light on the domestic and regional power struggle. It also describes some customs and heritage of Merina, the Malagasy tribe, living in and around the capital and surrounding highlands. Throughout the book, author eloquently describes Ranavalona’s brutality and questions her morals and sanity.

More reluctantly, Laidler also acknowledges several remarkable political and economic successes of the Queen. Her efforts turned (if only temporarily) the Merina-dominated nation into a self-sufficient, autonomous regional power in the western Indian Ocean. Imagine a female leader of a developing African country, being able to freeze the Franco-British trade in the region entirely. Only after the $15,000 in repatriation were paid by “the offender”, did she reverse her course on the matter.

Beyond the “mad queen” herself, the book tells the reader about a handful of extraordinary Europeans with close ties to the country. Jean Laborde started his “tenure” on the island as a mere castaway. The engineer is credited for contributing greatly to Madagascar’s “industrial revolution”. He was also Ranavalona’s lover and confidant until the day he got himself expelled from the country for staging a coup against her.

The “diplomatic” intrigues of another French character, trader Joseph-Francois Lambert, are also of historical significance. An agreement called Lambert Chapter, later became a major pretext of the French colonization of Madagascar.

Finally, a story about the Austrian solo female adventurer Ida Pfeiffer, made its way into the narrative. The lady described as “the world’s first independent traveler, eschewing “package tours” and setting out alone to whatever destination took her fancy”, never fully recovered from her trip to Madagascar. Her personal (and rather vitriolic) narrative of the “mad Queen” in “The Last Travels of Ida Pfeiffer: Inclusive of a Visit to Madagascar (1861)” was published in London just a few months before Ranavalona’s death and a few years after her own.

A few of Laidler’s critics argue that certain “facts” about the Queen described in the book are rather anecdotal in nature. However, his account of this prominent national character and the period of history she represented is certainly worthwhile.

Lords and lemurs: mad scientists, kings with spears, and the survival of diversity in Madagascar

By Alison Jolly. Houghton Mifflin. (2004)

This is a touching and humoristic autobiographical book written by a biologist Alison Jolly about Malagasy life. During her academic career, the author spent over 40 years studying behavior of ringtails and other lemurs in the unique spiny forest of the southern Madagascar. She became a close friend of her hosts and the founders of the Berenty Reserve, the aristocratic French De Heaulme family. Originally from the Reunion, De Heaulmes ran a local sisal factory and represented the largest employer in the area. Jolly also became deeply involved with the local Tandroy tribe.

Although written by a primatologist, the book is not a descriptive study of lemurs’ behavior. In fact, the amount of material about the local wildlife in the book is well balanced with its historical and ethnographic content. The author masterly and passionately navigates the complexity and cultural nuances of the Malagasy society, its traditional beliefs and customs. She also adds a human touch to the dilemmas of the “the Westerners”, who set out on their humanitarian, conservational and developmental missions in Madagascar.

The transformation of the Berenty Reserve into a thriving eco-lodge, following a dramatic downturn in the sisal industry, was one of a plethora of turning points described in the book. Currently, Berenty is one of the most popular tourist destinations in the Madagascar.

Lost People: Magic and the Legacy of Slavery in Madagascar

By David Graeber. Bloomington: Indiana University Press. (2007)

“Lost people” are devoid of their own land and therefore the blessings of their ancestors. And this is a great shortcoming in the minds of most descendants of the “nobles” and “free people” of Imerina.

Madagascar played a central role in slave-trade, which constituted a large portion of the regional economy in the late 18-19th centuries. Access to slave labor particularly important for the colonial plantation owners on Mauritius and Reunion in the western Indian Ocean. In addition, it fueled the domestic Madagascar economy under the Merina rule. As much as one third of the Merina Kingdom was represented by slaves by 1820 and served as a major labor force.

The book is based on extensive archival work and analyses of the 19th century Merina Kingdom documents. It is an ethnographic account of life in Befato, a rural community in the highlands, just outside of the capital Antananarivo. It’s mostly concerned with the cultural and social burden of slavery in postcolonial Madagascar. The collective history of this past imprinted on three different cross-sections of the modern Malagasy population: the andriana (the nobles), the hova (the free people) and the mainty (the slaves) and their collective and individual cultural identities.

Just like 200 years ago, slave descendants represent a large portion of the Merina population (close to one out of three, by some estimates). More than a century after slave labor was officially abolished, modern slavery-like practices and discrimination still exist in Madagascar.

Although the Graeber has been criticized by some experts in the field (most notably by Gwyn Campbell, a guru in the economic history of the Indian Ocean region) for his research sources and methods, the book serves its purpose as defined by the author himself. Rather than being strictly historic in nature, his work is, first and foremost, an ethnographic account of life and struggle of a small Malagasy community. The “oral memories” collected by Graeber provide a rich social context for deeper understanding of the local people you will encounter and interact with during your travels.

No time to read this long (over 400 pages) book about Madagascar? No problem. Try “Slavery and Post-Slavery in Madagascar: An Overview” instead. This manuscript was expertly written by Denis Regnier and Dominique Somda for the recent book “African Islands: Leading Edges of Empire and Globalization”. It might be all you need to get somewhat familiar with the topic. Also take a look UNECSO’s Slave Route Map to see how the slave trade originating in Madagascar, fits in the global slavery history.